![]() Part I

Part I![]()

1

THE ZEN MASTER WEPT

In late January 1999 I travelled to the village of Hara in Japan’s Shizuoka Prefecture to visit Zen Master Nakajima Genjō (1915–2000), the 84-year-old abbot of Shōinji temple and head of the Hakuin branch of the Rinzai Zen sect. Shōinji is famous as the home temple of Zen Master Hakuin Ekaku (1685–1768), the great medieval reformer of Rinzai Zen. Although I didn’t know it at the time, Genjō had little more than another year to live.

Genjō, I learned, had first arrived at Shōinji when he was only twelve and formally entered the priesthood at the age of fifteen. Eventually he became a Dharma successor of Yamamoto Gempō (1866–1961), who was abbot of both Shōinji and nearby Ryūtakuji temples, and one of the most highly respected and influential Rinzai masters of the modern era. In the immediate postwar period, Gempō was selected to head the entire Myōshinji branch of the Rinzai Zen sect.

In the course of our conversation, Genjō informed me that he had served in the Imperial Japanese Navy for some ten years, voluntarily enlisting at the age of twenty-one. Significantly, the year prior to his enlistment Genjō had his initial enlightenment experience (kenshō).

Having previously written about the role of Zen and Zen masters in wartime Japan, I was quite moved to meet at last a living Zen master who had served in the military. That Genjō was in the Rinzai Zen tradition made the encounter even more meaningful, for as readers of Zen at War will recall, none of the many branches of that sect have ever formally expressed the least regret for their fervent support of Japanese militarism. Given this, I could not help but wonder what Genjō would have to say about his own role, as both enlightened priest and seasoned warrior, in a conflict that claimed the lives of so many millions.

To my surprise, Genjō readily agreed to share his wartime experiences with me, but, shortly after he began to speak, tears welled up in his eyes and his voice cracked. Overcome by emotion, he was unable to continue. By this time his tears had triggered my own, and we both sat round the temple’s open hearth crying for some time. When at length Genjō regained his composure, he informed me that he had just completed writing his autobiography, including a description of his years in the military.

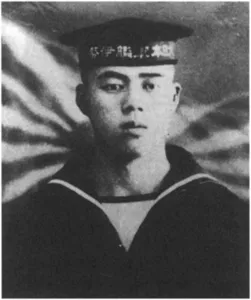

Genjō promised to send me a copy of his book as soon as it was published. True to his word, at the beginning of April 1999 I received a slim volume in the mail entitled Yasoji o koete (Beyond Eighty Years). The book contained a number of photos including one of him as a handsome young sailor in the navy and another of the battleship Ise on which he initially served. Although somewhat abridged, this is his story.1 It should be borne in mind, however, that his reminiscences were written for a Japanese audience.

In the Imperial Navy

Enlistment

I enlisted in the Imperial Japanese Navy in 1936. On the morning I was to leave, Master [Yamamoto] Gempō accompanied me as far as the entrance to the temple grounds. He pointed to a nearby small shed housing a water wheel and said

Look at that water wheel, as long as there is water, the wheel keeps turning. The wheel of the Dharma is the same. As long as the self-sacrificing mind of a bodhisattva is present, the Dharma is realized. You must exert yourself to the utmost to ensure that the water of the bodhisattva mind never runs out.

Master Gempō required that I leave the temple dressed in the garb of an itinerant monk, complete with conical wicker hat, robes, and straw sandals. This was a most unreasonable requirement, for I should have been wearing the simple uniform of a member of the youth corps.

I placed a number of Buddhist sūtras including the Platform Sūtra of the Sixth Zen Patriarch in my luggage. In this respect I and the master were of one mind. While I had no time to read anything during basic training, once assigned to the battleship Ise I did have days off. The landlady where I roomed in Hiroshima was very kind, and my greatest pleasure was reading the recorded sayings of the Zen patriarchs.

In the summer of 1937 I was granted a short leave and returned to visit Master Gempō at Shōinji. It was clear that the master was not the least bit worried that I might die in battle. “Even if a bullet comes your way,” he said, “it will swerve around you.” I replied, “But bullets don’t swerve!” “Don’t tell me that,” he remonstrated, “you came back this time, didn’t you?” “Yes, that’s true …” I said, and we both had a good laugh.

While I was at Shōinji that summer I successfully answered the Master’s final queries concerning the kōan known as “Zhaozhou’s Mu” [in which Zhaozhou answers “Mu” (nothing/naught) when asked if a dog has the Buddha nature]. I had grappled with this kōan for some five years, even in the midst of my life in the navy. I recall that when Master Gempō first gave me this kōan, he said: “Be the genuine article, the real thing! Zen priests mustn’t rely on the experience of others. Do today what has to be done today. Tomorrow is too late!”

Plate 1 Rinzai Zen Master Nakajima Genjō as a young priest. Courtesy Nakajima Genjō.

Plate 2 Rinzai Zen Master Nakajima Genjō wearing the uniform of a Japanese Imperial

Navy sailor attached to the battleship Ise. Courtesy Nakajima Genjō.

Plate 3 View of Nakajima Genjō’s ship, the Japanese Imperial Navy battleship Ise. Courtesy Nakajima Genjō.

Plate 4 Shōinji Temple located in the village of Hara in Shizuoka Prefecture. Both Zen Master Nakajima Genjō and Inoue Nisshō trained here. In prewar Japan this temple was headed by Rinzai Zen Master Yamamoto Gempō. Courtesy Nakajima Genjō.

Master Gempō next assigned me the most difficult kōan of all, i.e. the sound of one hand. [Note: this kōan is often wrongly translated as “the sound of one hand clapping”] “The sound of one hand is none other than Zen Master Hakuin himself. Don’t treat it lightly. Give it your best!” the master admonished.

Inasmuch as I would soon be returning to my ship, Master Gempō granted me a most unusual request. He agreed to allow me to present my understanding of this and subsequent kōans to him by letter rather than in the traditional personal encounter between Zen master and disciple. This did not represent, however, any lessening of the master’s severity but was a reflection of his deep affection for the Buddha Dharma. In any event, I was able to return to my ship with total peace of mind, and nothing brought me greater joy in the navy than receiving a letter from my master.

War in China

In 1937 my ship was made part of the Third Fleet and headed for Shanghai in order to participate in military operations on the Yangzi river. Despite the China Incident [of July 1937] the war was still fairly quiet. On our way up the river I visited a number of famous temples as military operations allowed. We eventually reached the city of Zhenjiang where the temple of Jinshansi is located. This is the temple where Kūkai, [ninth-century founder of the esoteric Shingon sect in Japan], had studied on his way to Changan. It was a very famous temple, and I encountered something there that took me by complete surprise.

On entering the temple grounds I came across some five hundred novice monks practicing meditation in the meditation hall. As I was still young and immature, I blurted out to the abbot,

What do you think you’re doing! In Japan everyone is consumed by the war with China, and this is all you can do? [The abbot replied,] And just who are you to talk! I hear that you are a priest. War is for soldiers. A priest’s work is to read the sūtras and meditate!

The abbot didn’t say any more than this, but I felt as if I had been hit on the head with a sledgehammer. As a result I immediately became a pacifist.

Not long after this came the capture of Nanjing (Nanking). Actually we were able to capture it without much of a fight at all. I have heard people claim that a great massacre took place at Nanjing, but I am firmly convinced there was no such thing. It was wartime, however, so there may have been a little trouble with the women. In any event, after things start to settle down, it is pretty difficult to kill anyone.

After Nanjing we fought battle after battle and usually experienced little difficulty in taking our objectives. In July 1940 we returned to Kure in Japan. From then on there were unmistakable signs that the Japanese Navy was about to plunge into a major war in East Asia. One could see this from the movements of the ships though if we had let a word slip out about this, it would have been fatal. All of us realized this so we said nothing. In any event, we all expected that a big war was coming.

In the early fall of 1941 the Combined Fleet assembled in full force for a naval review in Tokyo Bay. And then, on 8 December, the Greater East Asia War began. I participated in the attack on Singapore as part of the Third Dispatched Fleet. From there we went on to invade New Guinea, Rabaul, Bougainville, and Guadalcanal.

A losing war

The Combined Fleet had launched a surprise attack on Hawaii. No doubt they imagined they were the winners, but that only shows the extent to which the stupidity of the navy’s upper echelon had already begun to reveal itself. US retaliation came at the Battle of Midway [in June 1942] where we lost four of our prized aircraft carriers.

On the southern front a torpedo squadron of the Japanese Navy had, two days prior to the declaration of war, succeeded in sinking the British battleship Prince of Wales and the battle cruiser Repulse on the northern side of Singapore. Once again the navy thought they had won, but this, too, was in reality a defeat.

These two battles had the long term effect of ruining the navy. That is to say, the navy forgot to use this time to take stock of itself. This resulted in a failure to appreciate the importance of improving its weaponry and staying abreast of the times. I recall having read somewhere that Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku [1884–1943], commander of the Combined Fleet, once told the emperor: “The Japanese Navy will take the Pacific by storm.” What an utterly stupid thing to say! With commanders like him no wonder we didn’t stand a chance.

In 1941 our advance went well, but the situation changed from around the end of 1942. This was clear even to us lower-ranking petty officers. I mean by this that we had started to lose.

One of our problems was that the field of battle was too spread out. The other was the sinking of the American and British ships referred to above. I said that we had really lost when we thought we had won because the US, learning from both of these experiences, thoroughly upgraded its air corps and made air power the centre of its advance. This allowed the US to gain air superiority while Japan remained glued to the Zero as the nucleus of its air wing. The improvements made to American aircraft were nothing short of spectacular.

For much of 1942 the Allied Forces were relatively inactive while they prepared their air strategy. Completely unaware of this, the Japanese Navy went about its business acting as if there were nothing to worry about. Nevertheless, we were already losing ships in naval battles with one or two hundred men on each of them. Furthermore, when a battleship sank we are talking about the tragic loss of a few thousand men in an instant.

As for the naval battles themselves, there are numerous military histories around, so I won’t recount them here. Instead, I would like to relate some events that remain indelibly etched in my mind.

Tragedy in the South Seas

The first thing I want to describe is the situation that existed on the islands in the south. Beginning in 1943 we gradually lost control of the air as the US made aerial warfare the core of its strategy. This also marked the beginning of a clear differentiation in the productive capacity of the two nations.

It was also in the spring of that year that my ship was hit by a torpedo off the coast of Hainan island. As I drifted in the South China Sea, I groaned caught in the realm of desire, hovering between life and death. Kōans and reciting the name of Amitābha Buddha were meaningless. There was nothing else to do but totally devote myself to Zen practice within the context of the ocean itself. It would be a shame to die here I thought, for I wanted to return to being a Zen priest. Therefore I single-mindedly devoted myself to making every possible effort to survive, abandoning all thought of life and death. It was just at that moment that I freed myself from life and death.

This freedom from life and death was in reality the realization of great enlightenment (daigo). I placed my hands together in my mind and bowed down to venerate the Buddha, the Zen Patriarchs, their Dharma descendants, and especially Master Gempō. I wanted to meet my master so badly, but there was no way to contact him. In any event, all of the unpleasantness I had endured in the navy for the past seven years disappeared in an instant.

Returning to the war itself, without control of the air, and in the face of overwhelming enemy numbers, our soldiers lay scattered about everywhere. From then on they faced a wretched fate. To be struck by bullets and die is something that for soldiers is unavoidable, but for comrades to die from sickness and starvation is truly sad and tragic. That is exactly what happened to our soldiers on the southern front, especially those on Guadalcanal, Rabaul, Bougainville, and New Guinea. In the beginning none of us ever imagined that disease and starvation would bring death to our soldiers.

As I was a priest, I recited such sūtras as Zen Master Hakuin’s Hymn in Praise of Meditation (Zazen Wasan) on behalf of the spirits of my dying comrades. Even now a...