- 344 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Design Out Crime

About this book

Here is a book about the practical design of communities and housing in which people can enjoy a good quality of life, free from crime and fear of crime.

Recognising that crime, vandalism and anti-social behaviour are issues of high public concern, and that the driving forces behind crime are numerous, this book argues that good design can help tackle many of these issues. It shows how, through integrating simple crime prevention principles in the design process, it is possible, almost without notice, to make residential environments much safer.

Written from the perspective of an architect and town planner, this book offers practical design guidelines through a set of accessible case studies drawn from the UK, USA, The Netherlands and Scandinavia. Each example illustrates how success comes when design solutions reflect local characteristics and where communities are truly sustainable; where residents feel they belong, and where crime is dealt with as part of the bigger picture of urban design.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture GeneralChapter 1

Housing and Crime

Nature of Crime

Crime in housing takes on many forms: vandalism, i.e., the wilful destruction of objects and materials; burglary, i.e., theft carried out by breaking and entering into property; thefts of and from cars; racial crime; drug misuse; nuisance and antisocial behaviour against people in public and semi-public areas; domestic violence; sexual violence (particularly indecent assault and rape) in public and semi-public spaces. Patterns of crime in many housing areas show that the problems are frequently caused by a small number of persistent offenders who live nearby. In many instances, people have given up all hope that anything can be done. They do not even report crimes, such is their lack of confidence in a successful outcome.

It is important to understand the following principles:

Figure 1.1 “Fortress environment”. (Reproduced by courtesy of City of Haarlem Urban Safety Department.)

Extent and Cost of Crime

International Comparisons

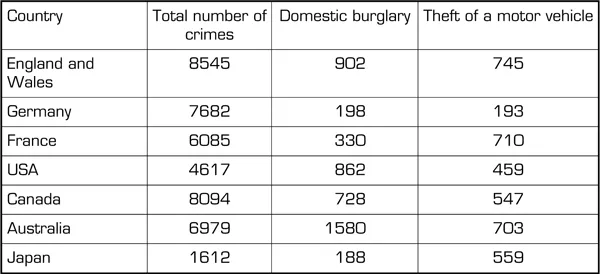

Comparisons between countries are most alarming. England and Wales top the international table for domestic burglary. Both countries have a higher burglary rate than the USA and over four times the rate of Germany (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Crime rates per 100,000 people, 1998, from police records for selected “comparator” countries

Schneider and Kitchen, p. 57. (Developed from Barclay G.C., and Taverns, C. (2000), and International Comparisons of Criminal Justice Statistics (1998), London, Tables 1, 1.1, 1.3–1.5.)

Of particular notice is the low level of domestic crime in Japan which is considered in Chapter 3 (p. 112).

Crime Levels in Britain

The magnitude of the current crime problem can be seen by looking at the 2001/02 statistics for England and Wales in the British Crime Survey (BCS). The survey refers to two types of figure – crimes reported to the police and estimates, based on interviews, that include crimes not actually reported. Based on interviews taking place in 2001/02, crimes against adults living in private households were just over 13 million. This represents a decrease of 2 per cent compared with the estimate for 2000 and a fall of 14 per cent between 1999 and 2001/02. However, these figures are still high. The total number of crimes recorded by the police in 2001/02 was 5,527,082, an increase of 7 per cent compared to 2000/01. Of the crimes recorded by the police, 16 per cent related to burglary, 18 per cent to theft of or from vehicles, 2 per cent to drug offences, 19 per cent to other property offences, 15 per cent to violent crime, and 30 per cent to other thefts and offences (Simmons et al., 2002, pp. 5–7).

The BCS estimates from its 2001/02 interviews indicate that there were 1,119,000 offences of arson and criminal damage (vandalism) in England and Wales, not including offences against vehicles. In terms of recorded crime, there was an 11 per cent rise in total criminal damage offences from 2000/01 to 2001/02. Excluding arson, 42 per cent (422,000) were to a vehicle and 27 per cent were to a dwelling (271,000). Many criminal damage offences were relatively minor. The number of arson offences recorded by the police rose by 14 per cent in the same period to 60,472 offences. Levels have risen by over 70 per cent since the mid-1990s (Simmons et al., 2002, p. 37).

Regional Variations

Domestic burglary rates vary widely from region to region and within each region. In 2001/02 the highest was in the North-East region (454 per 10,000 population), Yorkshire and Humberside (364), the North-West (310) and London (308). All of these were around double those of Wales (159) and the South-East (149), which were the lowest (Simmons, 2002, p. 35). Generally speaking, the highest rates of burglary are in metropolitan areas with the lowest in the commuter belt. The most commonly stolen items were cash, jewellery, CDs, tapes, videos and video recorders.

Household Variations

The British Crime Survey has consistently shown that the risk of burglary varies considerably across households with different characteristics and situated in different localities. The national average for households perceiving they are at risk of burglary from interviews in 2001/02 was 3.5 per cent. The percentage increased with type of accommodation: flats/maisonettes and council estate housing in general, 4.7 per cent; private renters, 5.7 per cent; houses with a high level of physical disorder, 6.8 per cent; head of household within the age 16–24, 9 per cent; and single parent, 9.3 per cent (Simmons et al., 2002, pp. 32–33).

Cost of Crime

Estimates place the cost of each domestic burglary in Britain at between £1,411 and £1,999 without consequential costs such as police, courts, probation, etc. If this kind of figure were applied to the number of domestic burglaries the total cost is in the order of £12 billion per year (Knights et al., 2002, p. 7). These costs are critical. They demonstrate beyond all doubt the significance of the impact of crime in housing and the benefits that could come from its prevention through design. The costs of designing to Secured by Design standards could be minimal in comparison (see p. 209). It is therefore important for everyone involved in the planning, design, management and maintenance of housing, especially at policy decision level, to understand this principle.

Crime Opportunity

Most crimes are committed because the offender can see the opportunity. This can be one or a combination of opportunities, such as easy access, places to hide, an absence of a clear definition between public and private space, poor lighting and landscape planting that can conceal someone’s presence. The more that offenders feel unsafe and vulnerable, the less they are likely to commit an offence. There are three basic criminological theories relating to crime opportunity:

- Rational choice that assumes that potential offenders will undertake their own risk assessment before deciding to commit a crime. They will consider the chances of being seen, ease of entry and the chances of escape without detection.

- Routine activities theory that assumes that for an offence to take place there needs to be three factors present: a motivated offender, a suitable target or victim and a lack of capable guardians. To prevent a crime it is necessary to alter the influence of one of these factors. For example, an offender can be demotivated by increasing the level of surveillance or by making access more difficult. A target can also be made less attractive by increasing security or removing escape routes. Creating a sense of neigh-bourliness, blending socio-economic groups and creating a lively street layout can be a deterrent.

- The defensible space theory applies to the different levels of acceptance that exist in order for people to be in different kinds of space. Offenders normally have no reason for being in private or semi-private spaces, so by distinguishing the spaces between public and private it is possible to exert a measure of social control in order to reduce the potential for crime and antisocial be...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword by Dr Tim Pascoe, Head of the Crime Prevention Research Unit, Building Research Establishment (BRE)

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Housing and crime

- Chapter 2: Development of design principles

- Chapter 3: Planning and design

- Chapter 4: Design guidance

- Chapter 5: Creating safe and sustainable communities

- Appendix

- Bibliography/References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Design Out Crime by Ian Colquhoun in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.