![]()

1

The Autotnaticity of Similarity-Based Reasoning

Kevin Biolsi

Edward E. Smith

University of Michigan

A recurring theme in Bill McKeachie’s writings about teaching and learning has been the importance of understanding students’ cognition (e.g., McKeachie, 1980a, 1980b). For example, one line of McKeachie’s work has focused on students’ cognitive structures of key classroom concepts, and how the form and evolution of such structures reflect on student performance (Lin, McKeachie, Wernander, & Hedegard, 1970; Naveh-Benjamin, McKeachie, & Lin, 1989; Naveh-Benjamin, McKeachie, Lin, & Tucker, 1986). Other work on learning strategies (McKeachie, Pintrich, & Lin, 1985a) and learning to learn (McKeachie, Pintrich, & Lin, 1985b; Pintrich, McKeachie, & Lin, 1987) has emphasized the importance of teaching students key concepts of cognitive psychology along with the learning strategies that make use of these concepts. The importance of such considerations is underscored by the recent review of teaching and learning in the college classroom by McKeachie, Pintrich, Lin, Smith, and Sharma (1990); in this document, a considerable amount of space is devoted to student cognition, including such topics as knowledge structure, cognitive and metacognitive learning strategies, and thinking and problem solving. In this chapter we hope to contribute to such work on student cognition, focusing on issues that are relevant to probabilistic reasoning and to training such reasoning.

When people are asked to judge the probabilities of various events, rather than employing principles of probability theory they might have learned in academic settings, often they rely on a number of informal heuristics (e.g., Kahneman, Slovic, & Tversky, 1982; Nisbett & Ross, 1980). One such heuristic is representativeness, whereby an event is judged likely to the extent that it is “(i) similar in essential properties to its parent population; and (ii) reflects the salient features of the process by which it is generated” (Kahneman & Tversky, 1972, p. 431). When the problem elements are instances and categories, then the degree of representativeness reduces to the typicality of an instance in a category, or the degree to which the instance is similar to the prototype of the category (Shafir, Smith, & Osherson, 1990).

To illustrate the representativeness, or similarity, heuristic, consider the following description: “Bill is 34 years old. He is intelligent, but unimaginative, compulsive, and generally lifeless. In school, he was strong in mathematics but weak in social studies and humanities” (Tversky & Kahneman, 1983, p. 297). Given this description, subjects judge Bill more likely to be an accountant who plays jazz for a hobby than just someone who plays jazz for a hobby, presumably because of Bill’s similarity to the prototypical (or stereotypical) accountant. Such a judgment violates the conjunction rule of probability, which specifies that the conjunction of any two events can be no more probable than either event by itself. In other judgment tasks, subjects have been shown to ignore or severely underweight prior probabilities or base rates of events in favor of similarity information, even though the use of such base-rate information is prescribed by normative theory (see Kahneman et al., 1982). Such reliance on similarity has been demonstrated in a number of domains with a number of different subject populations, including medical decision making (Travis, Phillippi, & Tonn, 1989), clinical judgment (Dawes, 1986), legal decisions (Saks & Kidd, 1986), and developmental studies with grade-school children (Agnoli; 1991; Jacobs & Potenza, 1991). In addition, the potential implications of the representativeness heuristic for school psychologists have been described by Burns (1990) and Fagley (1988).

In this chapter we build on the idea that the similarity heuristic is widely used because it is a type of “natural assessment” (Tversky & Kahneman, 1983). In what follows, we first interpret natural assessment as an “automatic” computation,1 where the notion of automaticity is drawn from studies of attention and memory. We then describe two experiments that demonstrate that similarity assessments exhibit at least one important property of automatic processes, namely that their execution is obligatory, given that the appropriate inputs occur. Finally we tie these results to work in education.

As alluded to previously, automatic processes have been intensively studied in the domains of attention and memory (e.g., Schneider & Shiffrin, 1977; Shiffrin & Schneider, 1977). In these studies, automatic processes are generally characterized by some combination of the following properties: They are unavoidable or obligatory once the appropriate inputs occur, they are effortless or require relatively little of one’s attentional capacities, they occur in parallel, and they are relatively fast. In the experiments described here, we focus on the first of these properties, namely the obligatory nature of similarity computations. This property of automatic processes is often studied within the paradigm pioneered by Stroop (1935; see MacLeod, 1991, for a comprehensive review of Stroop experiments).

In a variant of Stroop’s original experiments, subjects are presented with lists of words printed in colored ink. The subjects’ task is to name the color of the ink for all words in the list as quickly as possible. In one condition the words are neutral with respect to color (e.g., “take,” “friend”), while in a second condition the words are color terms (e.g., “blue,” “red”) printed in ink colors different from the colors they named. For example, the word “blue” might be printed in red ink, whereas the word “brown” might be printed in green ink. In these experiments, color-naming times are found to be significantly longer and error rates higher in the second than in the first condition. Furthermore, when color words and ink colors are congruent (e.g., “blue” is printed in blue ink), facilitation occurs in the form of faster reading times and fewer errors as compared to control items. These results indicate that subjects are unable to suppress reading of the word, and that the encoding and interpretation of the color word can then interfere with or facilitate naming its print color. Thus, the encoding and interpretation of a word is obligatory and, hence, an automatic process.

Like the encoding of a word, the assessment of similarity might be obligatory in the sense that it is manditorily performed whenever input information of the proper kind is presented. To test this hypothesis, we should be able to employ a variation of the Stroop paradigm in which information that automatically activates similarity computations is presented in a task that also requires computations of a second type, for example, computations of relative base rates or frequencies. By varying the degree to which the two processes lead to the same answer, we should observe both interference effects, in the form of increased response times and error rates, and facilitation effects, in the form of decreased response times and error rates, of similarity on frequency-based responses.

To illustrate, consider the description of Linda as “bright, outspoken and concerned with social issues” and the two categories bankteller and prominent feminist writer. If the task is to choose the category with the higher frequency, then bankteller should be chosen. However, Linda as described seems to be more similar to the typical prominent feminist writer than to the typical bankteller, so similarity leads to a different answer than does frequency. Thus, to the extent that the computation of similarity occurs more rapidly than that of frequency, and that the results of the similarity computation cannot be ignored, we should expect the response to such an item to be slower or less accurate when compared to an appropriate control. Similarly, if the two choices used with the Linda description are social worker and president of a cosmetics company, then both frequency and similarity lead to the same response, namely social worker, and we should expect facilitation in the form of faster and/or more accurate responses.

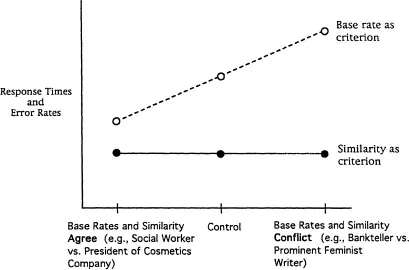

In our experiments, subjects were trained to make choices as just described using two different criteria: (a) base rates of the categories and (b) similarity of the descriptions to category prototypes. The predictions are displayed schematically in Fig. 1.1. Consider first those trials for which base rates are used as the criterion (the dashed line in Fig. 1.1). When the similarity and base-rate information agree (e.g., “Linda is a social worker” vs. “Linda is president of a cosmetics company”), we expect facilitation in the form of shorter response times and/or lower error rates than for suitable control items. When the two types of information conflict with each other (e.g., “Linda is a bankteller” vs. “Linda is a prominent feminist writer”), we expect interference in the form of longer response times and/or higher error rates relative to the control items.

FIG. 1.1. Predicted patterns of error rates and response times for experimental conditions.

Now consider those trials for which similarity to category prototype is used as the decision criterion. Because we do not predict automatic activation of base-rate computations, we do not expect such computations to intrude on similarity-based choices. Therefore, the response times and error rates should be relatively constant across the three conditions for the similarity-based trials, as indicated by the solid line in Fig. 1.1.

EXPERIMENT 1

Method

Procedure

Subjects were first given training materials that instructed them in judging relative likelihood using two different criteria: similarity to category prototype and frequency of category. The training materials briefly described the principles behind the two criteria and provided several examples with personality descriptions of the “Linda” type. Decisions based on similarities and frequencies are referred to as similarity decisions and probability decisions, respectively.

Following training, each subject performed the experiment seated at a computer terminal with a response panel. On each trial, a personality description was presented and remained on the screen until the subjects had read and understood it, and then pressed the appropriate response key. Following the description, either the word “Probability” or the word “Similarity” appeared on the screen for one second, instructing the subjects as to which criterion to use for their subsequent decision. Next, two category statements appe...