- 456 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Future Forms and Design For Sustainable Cities

About this book

Concentrating on the planning and design of cities, the three sections take a logical route through the discussion from the broad considerations at regional and city scale, to the larger city at high and lower densities through to design considerations on the smaller block scale. Key design issues such as access to facilities, access for sunlight, life cycle analyses, and the impact of communications on urban design are tackled, and in conclusion, the research is compared to large scale design examples that have been proposed and/or implemented over the past decade to give a vision for the future that might be achievable.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Section Two

Designing for Sustainable Urban Form at High and Lower Densities

7

The City and the Megastructure

Introduction

Are megastructures a form of sustainable development and do they hold any promise as a mode of urban development? It is believed that Fumihiko Maki invented the term in 1960s to describe large projects, even though his own schemes never reached the scale of a megastructure (Bognar, 1996). The nature of a megastructure, however, has not been clearly articulated. ‘Megastructures were large buildings of a particular kind, though what kind remains difficult to define with neat verbal precision’ (Banham, 1976, p. 7). Maki (1964) suggested a megastructure is a ‘ . . . large frame in which all the functions of the city or part of the city are housed’. He compares megastructures to Italian hill towns, with its frame being the hill on which the towns were built. A large frame (or supporting structure) implies a concentration of functions, similar to those contained by the walls in a medieval city.

Historical Examples

An understanding of what makes a development into a megastructure can be gained from a brief historical review. The Romans constructed buildings on a massive scale. With the fall of the Roman Empire some of these vast structures were transformed by their inhabitants into the fabric of their cities. Good examples are the Roman amphitheatre which has become the core of the city of Arles, and the Diocletian Palace located in Split in Yugoslavia. Diocletian’s Palace was built with the typical layout of a Roman military camp, a rectangle surrounded by walls with bisecting axes intersecting at the centre and ending up at the gates (Williams, 1985). Transforming this kind of structure into a city was relatively easy since the form of the structure was similar to that of a city from the outset. Today, the Diocletian Palace still represents about half of Split’s historic-city centre. After the fall of the Roman Empire, buildings of this scale ceased to be built in Western Europe, but the idea of the city contained in one structure never really went away. In the 16th century, for example, Pieter Bruegel painted the ‘Tower of Babel’ (Figure 7.1) (Brown, 1975). The significance of this painting was tremendous. It represented a miniature, a vertical city within a city’s walls. Arguably, this powerful image highlights important aspects of city design that have some contemporary relevance.

Figure 7.1

Building of the Tower of Babel, by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. (Source: Visionary Architecture by C.W. Thomsen, Prestel-Verlag, Munich, 1994.)

The Metabolists in Japan were the first to acknowledge the potential of vast structures in addressing aspects of Asia’s urbanism, and they were responsible for several megastructure proposals (Kikutake et al., 1960). It is not surprising that projects were conceived in a place like Japan since land there is scarce. The proposals did much more than simply stack dense floor plans on top of each another in order to deal with both the scarcity of land and increasing population densities. The Metabolists believed that cities should be designed to grow and change, and only the underlying structure should be permanent. The other elements, which they called units of the city, should be attached to permanent structures like flowers and leaves are attached to the branch, and should be easily replaceable.

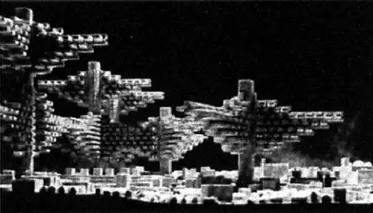

The idea of a permanent supporting structure with temporary interchanging units, which can be plugged in or removed also had a very significant influence on the work of the Archigram group. Where the designs of Metabolists presented themselves as projects to be built, Archigram’s work never presented itself as buildable. On the contrary, the Archigram images were designed to shock, to pose questions, and to challenge assumptions of patterns of living (Crompton, 1994). This challenge was reflected in the name ‘Archigram’, an abbreviation of Architectural Telegram, suggesting that the publication carried an urgent message (Figure 7.2).

Figure 7.2

Plug-in City by Peter Cook, Archigram, 1963–1964. (Source: Banham R. (1976) Megastructures of the Recent Past, Icon Editions, Harper and Row Publishers, New York.)

Habraken1 built further on Archigram’s ideas of permanent supporting structures with interchangeable units. In his book Supports: An Alternative to Mass Housing (Habraken, 1972) he defined a support structure as a:

. . . construction which allows the provision of dwellings which can be built, altered and taken down independently of each other. A support structure is quite a different matter from the skeleton construction of a large building. The skeleton is entirely tied to the single project of which it forms part. A support structure is built in knowledge that we cannot predict what is going to happen to it.

Habraken, 1972

Habraken identified that support structures were missing in temporary mass housing projects. His later work argues that a built environment is universally organized by form, place and understanding, three interwoven principles which roughly correspond to physical, biological, and social domains (Habraken, 2000). In many respects his highly influential work shows that ideas espoused by Archigram could be built (Habraken, 2001).

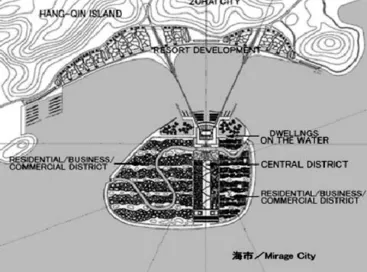

Isozaki’s work was probably closer to the Archigram’s ideas than to those of his Metabolist colleagues in Japan. His early project, ‘City in the Air’, designed in 1961, appears to have a basic treelike structure, but actually looking more like a forest than a tree (Figure 7.3) (Isozaki, 1996). Isozaki continued to challenge the Metabolists’ ideas through numerous projects and experimental exhibitions. More recently, Isozaki was commissioned to design Mirage City, near Macau (Figure 7.4) (Morioka, 1997). In this project, Isozaki considered the image of a New Utopia, allowing for new perspectives in a time of globalization. To emphasize global connections, Isozaki created a web page with his design and through the Internet-invited international architects and the public to contribute to the design (Tanaka, 1998). The design combined the principles of Feng Shui and geomantic technologies that were intended to reinforce the harmonious connections with nature, and led to a proposed man-made island approximately the size of Venice. In the design process, Isozaki also used a computer-simulation program in order to create various scenarios within the city.

Figure 7.3

City in the Air, by Arata Isozaki, 1962. (Source: Thomsen C.W. (1994) Visionary Architecture, Prestel-Verlag, Munich.)

Figure 7.4

Plan of Mirage City, by Arata Isozaki, 1996. (Source: Catalogue of the Venice Biennale 1996.)

It is clear that Isozaki’s work does not belong to Metabolist theory. Where the Metabolists’ architectural concepts were grounded in a linear conception of time and growth, Isozaki’s work sought to escape from these constraints, entering a more complex labyrinth of time and space, to create more organic systems capable of dynamic and complex growth. Isozaki represents the post-Metabolist movement, which has become known as ‘neovitalism’,2 which concentrates on developing more organic systems, capable of dynamic and complex growth (Hanru, 1999).

Although Archigram emerged in Britain, and without a doubt influenced many architects and planners during 1960s and early 1970s, British ‘megastructure’ projects could never compare in scale with the Japanese ones. The Byker estate (Figure 7.5) in Newcastle (Erskine, 1982) is one of the biggest; the complex was intended to be one mile long, with one elevation almost blank as a screen from the north winds and the adjacent highway. The other elevation is rich with balconies and windows. Here the megastructure was not just the architect’s dream; Erskine invited the tenant’s cooperation in designing the project, making the Byker estate an early attempt to create a dialogue between architecture and the community (Sharp, 1990). There are other examples of megastructures in Britain, like the Brunswick Centre in London, designed by Leslie Martin and Patrick Hodgkinson for Camden City Council, but the vision of megastructures as an approach to city design was not well received either in Britain or Europe. It was too often impractical to build structures for large populations in one project, and financing was not sympathetic to such a scale. Above all, population growth and housing shortage in Western Europe is not of the same scale as in South-East Asia.

Figure 7.5

Byker estate, by Ralph Erskine, 1978. (Source: http://www.greatbuildings.com/cgi-bin/gbi.cgi/Byker_Redevelopment.html/cid_1803148.gbi)

Megastructures in Hong Kong

Such problems of scale do not exist in Hong Kong. Here, the need to accommodate an ever-increasing number of people, combined with an acute shortage of land, has led to the development of various types of megastructures.3 Hong Kong’s megastructures are not the result of any urban theory. The fundamental force behind these developments is the necessity to provide accommodation for a rapidly increasing population, and so in Hong Kong, high-density, high-rise living became the norm. Most of the population live in high-rise ap...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Section One: The Big Picture: Cities and Regions

- Section Two: Designing for Sustainable Urban Form at High and Lower Densities

- Section Three: Aspects of Design for Sustainable Urban Forms

- Conclusion: Future Forms for City Living?

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Future Forms and Design For Sustainable Cities by Mike Jenks,Nicola Dempsey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.