One

Palladio’s children

His villas still speak to us. Their quiet dignity appeals to both lay person and professional. Ancient houses left standing in the countryside display classical façades with columns, entablature, stairs and monumental doors in exquisite proportion that seldom fails to seduce.They evoke nostalgic memories of households living a life of ease and luxury, seemingly so much more noble than our own.

But with Palladio there is more: surprising juxtapositions executed in a relaxed balance of volumes; lucid geometry; impeccable proportions; and the sure craftsmanship of simple details in masonry, in modest brick and plaster with occasional stone. And always, there is the innate good taste of buildings at ease with themselves. Such qualities silence any hastily formed associations and analogies.They transcend our notions of function, history and iconography. As architects, we recognize a colleague, a guild master who, in spite of more than four hundred and fifty years’ distance, we yearn to see as one of us.

We know, deep down, when form is good. Ordinary built environment has its own ways. It is guided by gravity, by territorial control and no less by customs of construction. Architecture such as Palladio’s, set against the canvas of such ordinary fabric, makes everyday environment shine. In so doing, it is rendered timeless, free of contemporary style and symbolism. We recognize that quality in his work.

1.1–1.4 Palladio’s imprint

1.1 Villa Rotonda, view from the entrance gate.

1.2 Villa Rotonda, stair at the back of the building, close to the retaining wall.

1.3 Villa Rotonda, detail of porch steps showing column bases.

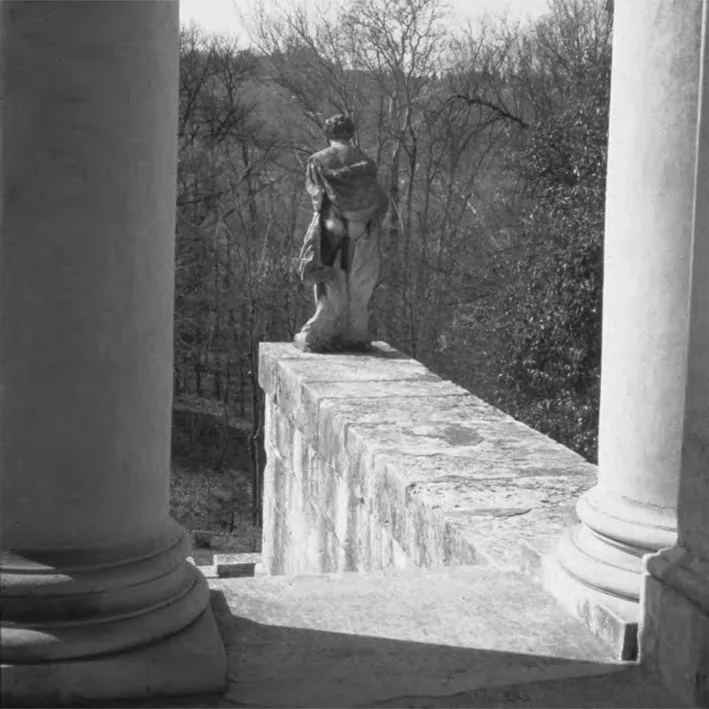

1.4 Villa Rotonda, sculpture viewed from the porch.

Others, equally impressive in their own ways, built in that remarkable Renaissance era. There are Donato Bramante’s innovations, Filippo Brunelleschi’s daring and poetic craftsmanship, Leon Battista Alberti’s intellectual illumination. In Venice, there is also Mauro Codussi’s sure yet unobtrusive assertion of power; and, in another culture, Sinan’s orchestration of monumental projects. These architects also produced lasting monuments that reveal unquestionable mastery. And yet, there is a clear distinction: we see them as individuals attached to their time.

It is not just the work that attracts us. Palladio, as a colleague, has outlasted even Modernism’s attempt to sweep the field clean. We no longer follow his classical precepts, but he is with us still. We recognize in Palladio’s work a familiar attitude toward making architecture, one that we share.We still view ourselves much in the way he may have seen himself.

In examining how we explain ourselves as architects today, we do well to look first at Palladio. He was the first to publish his oeuvre during his own lifetime. It was an unprecedented act with far-ranging results.1

A few decades earlier, Sebastiano Serlio (1475–1554) had published a selection of buildings that would establish the canons of Renaissance architecture.2 Unlike Leon Battista Alberti’s intellectual reflections on the nature of architecture in a new era, Serlio’s designs were intended to enlighten and inspire peers and clients alike. Serlio was not the first after Vitruvius Pollio, the Roman architect who wrote around the time of Jesus, to show examples of architecture, but the quality of Serlio’s drawings and the variety of subjects set a new standard. Above all, Serlio’s are books of drawings: The text is secondary.

Palladio had previously (1554) published a popular scholarly guide to Roman architecture, Le Antichità di Roma.3 In The Four Books on Architecture, Palladio, like those before him, professes to follow the traditional format set by Vitruvius in The Ten Books on Architecture. Yet while Palladio adopts the picture book format of Serlio, he comes across as a practicing architect and a former master mason erecting buildings to exacting standards. He informs and educates by reporting on ancient buildings he himself has measured and by showing his own designs – most of which have actually been built.

Only the second book gives us his renowned villas and urban palaces. But the publication as a whole projects a consistency in style and a preoccupation with balanced composition. As a result, The Four Books on Architecture was primarily understood as a representation of Palladio’s way of working. In Serlio’s writings, the author is rather academic, full of ideas but lacking practical judgment. But Palladio’s books show a master builder at work. He is occupied with matters of style and proportion and construction. He is working for real clients.

The innovative nature of Palladio’s publication was not lost on his readers. The Four Books on Architecture came to be seen as the record of a personal oeuvre and, as such, of a new way of defining architecture.

In the course of time, after many others, Le Corbusier would also follow Palladio’s example, recording his own twentieth-century work. In fact, Le Corbusier did so with a vengeance. He published the buildings, but also notebook sketches and notes, observations and ideas. New volumes of his ongoing record appeared every few years.4 They greatly reinforced a popular view of architecture as the story of gifted and successful individuals. More than ever, having one’s work published – preferably during one’s lifetime, and including cocktail napkin sketches – became the defining mark of arrival: of admission to the inner circle of those who define architecture.

Today, it is hard to exaggerate the importance of the published oeuvre in establishing what architecture means to us; the ways in which publication shapes perception, and also how we view the architect.

Such was the absolute authority of Palladio’s published work that for centuries the mere act of publication lent credibility to subsequent generations of architects.As a multitude of monographs and web sites unleashes an endless torrent of project information, the prestige associated with publication is now on the wane. Such sources less and less represent accolades of excellence, and more and more present uncritical vehicles of marketing and selfpromotion.

Yet prestige and personal vanity are the least significant aspects of published architecture. Far more significant is the fact that visual representation of the building, rather than its actual presence in the field, has come to define what architecture is – and what it is not. The number of signature buildings and places we know intimately through published or projected images far exceeds the number we have experienced in real space.We know the buildings, but not their context.Visitors experience an environment in which the building resides. Readers do not. The common references of the architectural profession reside in a common domain that is no longer a space – a city, or a country – but within the media of representation, themselves.

Here again, Palladio was a pioneer.We may assume he had his oeuvre printed to inform his peers in Rome and Florence of his contribution to the new way of making architecture. The stylistic world they were creating was neither Venetian, nor Roman, nor Florentine. Soon, it would not be solely Italian. As Palladio’s example came to inform his peers far beyond the Alps, the printed image bound together a new profession that shared an architecture without a context.

Classicism and neo-classicism bound the profession to a broader social class defined by privilege, taste and education, a class that also included lawyers, prelates, savants, statesmen and noblemen. Architects were no longer defined as Venetian or Parisian, Italian or Anglo-Saxon. Eventually, with the rise of the International Movement, the professional community acquired an identity apart; it has subsequently become increasingly selfreferential. Architecture went from identifying a locality or a culture to “-isms” that identified groups of practitioners who shared a way of making. It has finally ended up as the story of a grab bag of talented individuals, assembled however the individual historian or critic sees fit. Architects are no longer selected on the basis of their native place or people, but for their reputation within the worldwide network of cognoscenti.

If, finally, architecture is what architects do, here again it was the master architect Palladio – no doubt unwittingly – who came first, on the strength of his book: Prior to Palladian architecture, no architecture had been named after a single practitioner.

Palladio’s woodblock prints indicate no context. We remain unaware of abutting public spaces or neighbors. We see neither landscape nor topography in the representation of the villas.

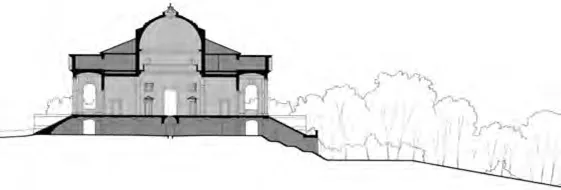

In the case of the Villa Almerico-Capra, best known as the Villa Rotonda, Palladio informs us that the site offers beautiful views in all directions, that the building is placed on a small hill with easy access. But he informs us neither of the masterly way he orchestrated the approach to the building nor how he provided it with access to the surrounding estate. In fact, he shows only a building plan, a section and a façade.

This is typical of the entire representation of his oeuvre: Palladio tells us about his clients. He recounts how noble and important they are: emphasizing that he reports on real buildings built for real people. But the buildings themselves are represented as abstract models divorced from site or context.

Palladio does not deny that a building should be well placed in relation to a road, a hill, a river or the orbit of the sun. In the tradition of Vitruvius, he devotes several pages to the issue of choosing a good and healthy site. But the architecture that Palladio was conveying to his peers in Rome and Florence had to do principally with the geometry and composition of buildings. The actual topic of The Four Books on Architecture is how to compose good buildings.

The non-site-specific graphic presentation of architectural objects made Palladio’s work eminently useful for distant designers and clients. It was left to them to decide how to adjust these models to accommodate environments and cultures of which Palladio could scarcely have dreamed.

We still live with the ambiguity of this legacy. Architects up to the present day habitually provide minimal information about site or context: as little as they can get away with when the setting is ordinary. Architectural photographers, editors and authors routinely keep us in the dark about surrounding everyday environment. In urban and suburban settings, Palladio’s example is followed to the letter, and for the same reason: the ongoing conversation in which published buildings participate is not local. It is a dialogue carried out within a distantly scattered network of peers. Architecture, from Palladianism onwards, has largely been a matter of exquisite signature objects. Site and context are brought to bear to the extent that they serve to heighten the audience’s appreciation of the dexterity of the author.

Paradoxically, contemporary architects simultaneously participate in another decidedly non-Palladian tradition, in which the building grows from the landscape, as opposed to being set as an object in it. This wrightian site-driven way of consciously shaping and placing form – subsequently adopted by Alvar Aalto, Sigurd Lewerentz and Alvaro Siza, among many others – connects to the age-old tradition of hands-on master building and vernacular building in immediate connection to the land and its local material resources. This is also part of our architectural sensibility. It further increases the tension between the local act and the global dialogue in which our publications engage. Photographs of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Falling Water cannot adequately convey how the building relates to the land. And the more such architecture specifically responds to the rise and fall of the land, to rock outcroppings or specimen trees, the less the design becomes exportable. This is one reason why emulation of Wright is so often disappointing: A building conceived in dialogue with the land does not travel as easily as a building whose parts relate only to one another.The first must be conveyed as a way of working, the latter can be transported as an object.

The well-sited object that is expertly placed in context – rather than grown from it – comes from a venerable and widespread tradition. The most conspicuous example is monumental architecture, which throughout history has tended to establish symmetrical selfcontainment. In a humbler vein, much of the North American rural and suburban tradition is one of wooden boxes erected along streets or in the landscape. In earlier times, they were impermanent, lifted from their foundations and rolled on logs to new locations as need arose.

The Palladian approach places itself within this tradition. If Palladio’s wood print images suggest models, his architectural purpose was likewise to objectify the building, to distinguish it from the landscape.

Perhaps none of Palladio’s buildings is as self-contained as the Villa Rotonda. It is sited with great sophistication. From the gate at the public road, the visitor is led through a narrow driveway cut through a rim of the hill, sloping upwards. Ascending on axis between the walls, one first sees the building’s monumental façade straight on. It is elevated, tightly framed by the walls of the entryway. [Fig. 1.1.] As one attains the level of the building, space opens to the left and right. Although the monumental steps of the portico lie directly ahead along the axis followed, one cannot continue straight ahead: the driveway splits and turns to access them sideways. This dramatic approach establishes a firm major axis for the perfect multiple symmetry of the building and the uniformity of its four elevations.5

1.5 Villa Rotonda, section showing the basement floor with access to farmland below the retaining wall. Based on an illustration in Camillo Semenzato’s The Rotonda of Andrea Pallad...