![]()

Chapter 1

Lifelong learning and the learning society

This trilogy endeavours to analyse a wide variety of aspects of lifelong learning and the learning society. In the first volume we showed how learning underlies our humanity: humans learn because we are consciously alive and that our learning is not only cognitive but all that makes us human beings which is added to our bare animal existence is learned. In this sense, learning must be life long. In the second volume, we explored elements of the learning society and noted how the current social conditions of globalisation have given rise to the knowledge economy, which might be regarded as a learning society. We also questioned the moral basis of this society. While the first volume primarily utilised ideas from both psychology and philosophy, the second was sociological but since it is about a society, it could also have been political. If the society that we call a learning society is not a just society, then it is incumbent upon us to explore how it can become one, even if it is not a utopian one. Justice is a legal concept that can also be judged by its morality and, consequently, it is important that we examine human learning and the learning society from both a political and moral perspective. This takes us into different realms of thought and we will touch on ideas in our investigation about which vast amounts of literature has been written but this volume will not be able to explore all of it, even if I had the ability. But we should not talk about a just learning society without exploring these concepts, even without asking even more fundamental questions about learning and the learning society.

Among the aims of this volume, therefore, is one which begins to open up some of the political questions that underlay the learning society; another is to critically examine the processes that occur against ethical criteria; a third aim is to examine the interplay of politics, economics and ethics in the learning society; finally, it aims to look to ask what type of society is possible as a result of learning. Since a great deal of the argument has already been constructed in the previous two volumes, it is necessary to understand the argument thus far. Consequently this opening chapter briefly revisits the previous two volumes and, in the process, develops the ideas just a little further. The first part of the chapter returns to the first volume and briefly re-examines the theory of lifelong learning that was discussed in it and in so doing a few additions are introduced to the argument, although the fundamental position remains unchanged. Likewise, the second part returns to the sociological arguments of the second volume in which it was argued that the learning society has been generated by global capitalism: it revisits the model of globalisation and examines the interplay between these forces and the responses of international, national and regional governments and organisations. There was a brief discussion of power in the second volume, but this chapter will conclude with a more extended discussion.

It is also important to explore global capitalism even more thoroughly in order to understand the political and moral issues with which we are confronted and this we will undertake in the next four chapters of this book; thereafter, we will develop our notion of social relations and the moral good and how this is, itself a learned and learning phenomenon. Underlying the whole of the trilogy is the recognition that since humanity continues to learn, the human project is not complete; therefore, realising the learning society is a complex phenomenon which may never be finalised since the only time when it might be regarded as complete is when human beings cease to learn which, while a fascinating concept, is never likely to occur and so we are never dealing with a ffinished product’ or even a finishable one.

Lifelong learning

In this section we will examine the processes of learning, recognising that they are both existential and experiential and so we will briefly look at the nature of experience and, finally, in this section we will examine the fact that learning and experience always occur within the life-world and so we will look briefly at the nature of socialisation and culture. This is necessary because the society in which we live is also an information society and since we are exposed to a tremendous amount of information we are presented with many opportunities to learn. In the second part, we will then examine the way that the social context of human learning is constructed by looking at globalisation and the forces that influence the nature of culture.

The learning processes

Learning is an existential process that might well begin just before we are born, and probably ends when we lose consciousness for the last time. We defined lifelong learning in the first volume as:

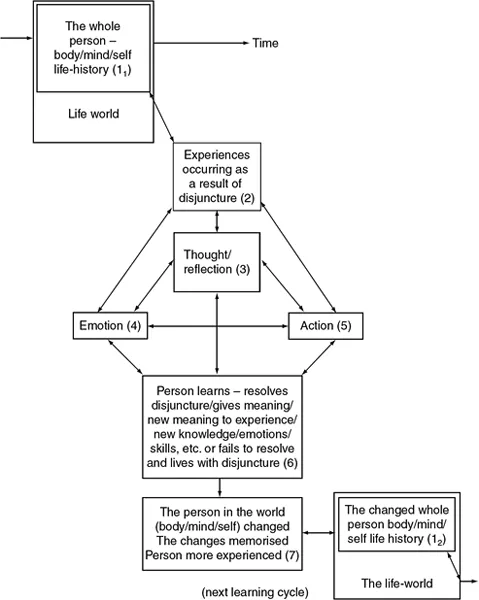

It is life long but dependent upon our experiences of the world in which we live so that it is more than just a psychological process – it is a human process and may, therefore, be studied from a wide variety of academic disciplines (Jarvis and Parker, 2005). This approach differs from many studies of learning in that it starts from the person of the learner – both body and mind – and recognises that it is from the learners’ experiences that learning actually occurs, but that those experiences are not all cognitive and that the different elements of any experience are transformed cognitively, emotively or through active engagement with the world and the ensuing learning integrated into the person’s biography. It is as a result of learning that the person is changed, becomes more experienced and grows and develops. A diagram of the learning processes was produced (Jarvis, 2006, p. 23) and the diagram below is a slight adaptation of it, made only to emphasise the learning that occurs.

Box 11 depicts the situation of people in their life-worlds and we shall look at this in greater detail below but we would argue that learning stems from social experience but that experience is determined to some extent by the nature of both the body and the mind in relation to each other and the external world. However, we continue to live in a taken-for-granted situation until such time as a situation causes us to question this taken-for-grantedness. Hence the arrow from box 1 pointing forwards in time that merely depicts the unquestioning process of much daily living. It is in the social situation that people are most likely to experience disjuncture (box 1), although this state can occur when people are alone, reflect on previous events, or even when they have an experience in interacting with the natural world, so that not all disjunctural experiences occur as a result of language and interaction as some social con-structivists hold (see Archer, 2000, pp. 86–117). The state of disjuncture occurs when we can no longer presume upon our world and act upon it in an almost unthinking manner; it is at this point that we have an experience (box 2) and it need not be contained within the bounds of language. Indeed, it can and does precede language in small children and in inexplicable situations (Jarvis, 1987, 1997). Experience can be transformed by thought, emotion or action (boxes 3–5), or any combination of them: the precise mechanisms of these transformations constitute considerable studies in their own right and these have not been undertaken here. Box 6 is a new addition to the diagram and it is included to underline the fact that the outcome of the transformation is that people actually learn or fail to resolve their disjuncture, but this process itself always results in a changed person, even when there is apparently no learning since the experience still affects the self of the learner (box 7). When people fail to resolve their disjuncture they can either learn to live in ignorance or with an awareness that they need to learn in order to resolve their disjuncture, or they

can start the whole process off again. But even when they have learned the process of living is on-going and so, then, is the process of learning as box 12 indicates.

Since the person is at the heart of the learning processes, it is necessary to recognise that persons are both mind and body, and that experiences do not occur only in the cognitive dimension but also in the physical and the emotional ones. Experience, itself occurs at the intersection of the person and the natural or social world and it occurs when individuals cannot take their lifeworld for granted and need to ask questions about their situation, such as – What does it mean? What do I do? What is that smell? – and so on. Experience, then, occurs in two dimensions: the dimension of the physical senses (body) and that of the mind, and in many instances these experiences occur simultaneously although for heuristic purposes we separate them here.

In all experiencing and learning, the process begins with the bodily processes of sight, smell, sound, taste and touch. In itself each sense experience is meaningless but we need to give it meaning and name it. When we can do this, and recall it then we can begin to take our sense experiences for granted and yet still have cognitive disjunctures, but in many instances our disjuncture begins with these sensations. We will all, no doubt, recall that game where we have to guess the nature of an object from a picture taken from an unusual angle, or when we are asked to feel something that we cannot see, and say what it is. These games build on the idea of disjuncture – we cannot take the taste, touch, sight, and so on for granted. Children probably have more disjunctural experiences that stem from sense experience than adults since they do not have the cognitive apparatus to give meaning to them in the first instance. It is only as we grow that we gain that knowledge to cope with them. Initially children have sense experiences that they cannot explain and so they live in ignorance of which they may be unaware in the first instance. However, as they mature so they begin to give meaning to those initial sensations of sight, smell, sound, taste, touch, and their learning moves from the senses to the cognitions and the knowledge they learn from the sensations is conveyed in language and so later learning occurs primarily in the cognitive domain and the sense experiences relegated to a secondary position. Consequently, as we mature the more our learning assumes a cognitive dimension but there are still times when we have a sense experience that we cannot explain in language – a disjunctural experience – and so we are forced to revert to the senses until we can give it meaning. In a way this was the problem that Knowles (1970, 1980) tried to deal with when he wrote his book on The Modern Practice of Adult Education – the first edition he sub-titled Andragogy versus Pedagogy, but as a result on the ensuing academic debate the revised edition was sub-titled From Pedagogy to Andragogy.Yet he never really resolved his problem and the reason was probably because he did not distinguish learning from the senses and the emotions from learning from the cognitions, and so he was unable to clarify any relationship between children’s learning and adult learning (Jarvis, 2007b). Adults continue to learn through the senses and both emotions and skills may be included here although in both cases there is also a cognitive dimension, so that they may also be placed within the diagram (Figure 1.3) as well.

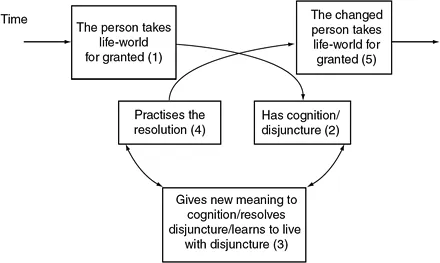

All learning begins with the sensations and so we may depict this form of learning (see Figure 1.2).

In Figure 1.2, we see that the disjuncture is caused by an inability to take the

sensation for granted: we cannot give it meaning or we are unsure about the meaning we give it, and so we need to resolve the dilemma caused by the experience (box 2). Having got an answer to our problem, i.e. we can give meaning to the sensation – as a result of self-directed learning, teaching, and so on (box 3) – we are able to practise it in a social situation. If our answer is acceptable in as much as the people upon whom we practise our answer do not contradict us in some way, then we can assume it to be socially correct even though it may not be technically correct. As we continue to practise it, so we are able to universalise it and take it for granted, until the next time that a disjunctural situation occurs. Kolb (1984) actually includes generalisation in his learning cycle, but my research does not suggest that generalisation occurs immediately following a new learning experience but only after we have tried out the resolution to our disjuncture on several occasions. If we do not resolve the dilemma, then we revert to box 2 and try again, so that the arrows between boxes 2 and 3, and between 3 and 4, are not uni-directional illustrating that there is a process of trial and error learning at both stages. At the point of taking our sensations for granted, we move to the next phase – when we discuss meaning itself rather than the sensation. Adults and older children are more likely than young children to experience disjuncture in the cognitive domain and so we can depict this learning experience (see Figure 1.3).

The process is the same as that of learning from sense experience, although in this situation the experience from which the learning began is fundamentally different, being cognitive, and depends on the fact that learning from sense experience has already occurred and is taken for granted. It is significant that primarily this is still a sense experience since we hear the sound of the words but the sounds have been relegated and the meanings take precedence. The

cognition, however, can be knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, values and even the knowledge associated with skills.

Naturally, there is also a thi...