This is a test

- 257 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Water, Sanitary and Waste Services for Buildings

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Water, sanitary and waste services represent a substantial proportion of the cost of construction, averaging 10% of the capital costs of building and with continuing costs in operation and maintenance. Nevertheless, they are often regarded as a 'Cinderella' within the building process. Parts of many different codes and regulations impact on these services, making an overall viewpoint more difficult to get.This new edition of this classic text draws together material from a variety of sources to provide the comprehensive coverage not available elsewhere. It is a resource for the sound design, operation and maintenance of these services and should be on the bookshelf of every building services engineer and architect.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Water, Sanitary and Waste Services for Buildings by A.F.E. Wise, John Swaffield in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Construction & Architectural Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Water Use,

Load and

Storage

Estimation

Over half of the potable water supplied by public water undertakings in the UK is used in buildings of various kinds. It is required for what is commonly termed domestic use, including all the various water-using activities in the home and also the supply to sanitary and kitchen accommodation in offices, schools, hospitals and elsewhere. The designer of building services requires a wide range of information on water usage. His or her concern is with the demand in classes of building and in individual buildings, with the requirements of the various water-using activities and with the patterns of use that develop in occupied buildings, all with the objective of estimating the water storage requirements and the flow loads that are likely to arise from the intermittent use of many different sanitary appliances. This requirement is by no means easy to satisfy. It demands both practical information on water usage in occupied buildings related to information about the use of the buildings themselves, and a theoretical framework within which to fit the data so obtained and to provide a basis for a design method. Statistical and probability considerations provide the necessary framework for the theoretical analysis and design procedure, but suitable practical data on water demand and patterns of use are much harder to come by. Experimental work to provide such data must be designed carefully and carried out thoroughly if it is to be at all useful. It may be necessary to monitor such quantities as the total supply to a building and its variation throughout the day, the variable flows in branches within networks of piping, the frequency of use of the sanitary appliances, and the actual quantities discharged to the drains.

It is not surprising, therefore, that the experimental investigations in this general field have been few and far between. They have been mostly carried out by national institutes concerned with building research and by universities. Designers, therefore, have been obliged to make do with very limited practical information, to use it within as sound a theoretical framework as possible, and to make up for the lack of reliable data by engineering judgement.

Water use

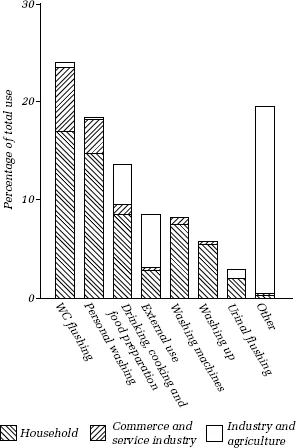

We turn now to some practical data that set the scene for considering load estimation. Tables 1.1 and 1.2 and figure 1.1 (DOE/WO 1992), the latter assuming a total use in England and Wales of 13000 Ml/day, summarize information which is not intended for direct design use but gives useful indications. Thus the consumption of water in WC flushing and for washing and bathing in dwellings suggests that these appliances merit careful attention from a load-producing standpoint. Urinal flushing is seen as a substantial consumer of water in commerce and industry. Changes in the amount of water used, for example a reduction in WC cistern capacity, would affect the overall picture in the course of time — see table 1.2. Water economy is dealt with in chapter 11 which has further information on usage.

From the design standpoint, it is necessary next to consider how the water-using activities and hence the consumption of water are distributed throughout the day. It is obvious that the influence of the large use of water by WCs is likely to vary depending on whether it is distributed evenly throughout the day or whether it is concentrated in several peak periods. The substantial use of water by urinals occurs at regular intervals throughout the day with automatic flushing. These simple examples serve to illustrate the importance of knowing something of the pattern of water-using activities in different classes of building.

Table 1.1 Water use as percentage of total use in major sectors (based on DOE/WO 1992)

| Activity | Household (55% of total use) | Commerce and service industry (15% of total use) | Industry and agriculture (30% of total use) |

| WC flushing | 31 | 35 | 5 |

| Personal washing | 26 | 26 | 1 |

| Drinking, cooking and food preparation | 15 | 9 | 13 |

| Washing machines | 12 | 8 | — |

| Washing up | 10 | 2 | — |

| Urinal flushing | — | 15 | 2 |

| External use | 5 | 4 | 17 |

| Other | 1 | 1 | 62 |

Table 1.2 Domestic consumption from studies in south west England (Hall et al. 1988)

| Consumption (litres per head per day) | ||

| Activity | 1977 | 1985 |

| WC flushing | 32.5 | 32.6 |

| Personal washing | 35.9 | 41.1 |

| Drinking and cooking | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| Washing and cleaning | 12.4 | 14.0 |

| Laundry | 13.4 | 18.2 |

| Waste disposal units | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| External use | 5.1 | 9.1 |

| Other use | 5.6 | 11.3 |

| Total | 110.0 | 131.6 |

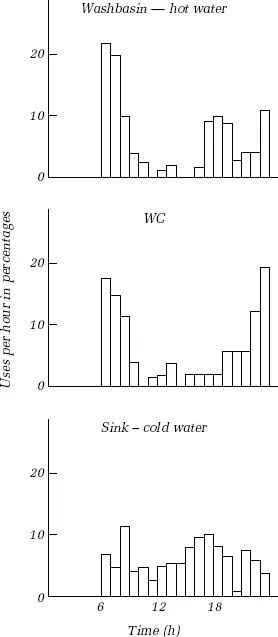

Few data are available and perhaps the most extensive investigation was carried out in a block of flats in London, using instrumentation and also involving the use of questionnaires (Webster 1972). Figure 1.2 illustrates in a simplified form some of the data obtained on the pattern of water-using activity throughout a typical weekday in the larger flats studied. The major activities in this study were washing, using the WC and preparing a drink, and these consistently accounted for about 80 per cent of the total. Broadly speaking there were three main periods of use of the sanitary appliances, both in the larger flats (two and three bedroom) which were in the main occupied by families with one or two adults working and in some 55 per cent of which there were children, and also in the smaller flats (single bedroom) where many occupants were retired. These periods were from 06.00 to 09.00; from 17.00 to 20.00; and from 21.00 to 24.00. Use of the sink was rather more uniformly distributed throughout the day than use of the WC and washbasin. It is to be noted that these records relate to use of the water supply outlets, and that many of the uses would not have involved filling the basin or sink with water — although there is no direct evidence on that aspect. The latter is more significant as far as the estimation of hydraulic loads on the soil and waste pipe system is concerned, a point to be discussed later. As a detail not recorded in these illustrations, the questionnaire showed that, for this sample, bathing was distributed throughout the week and there was no evidence of a particular period when use of the bath was favoured.

Figure 1.1 Estimated total water use in England and Wales

Note: Results in terms of average number of uses per hour as percentages of uses for the day

Figure 1.2 Examples of average weekday water use in flats

More recently, a small-scale diary survey was carried out by Butler (1991) with 28 households of one to five people living in houses in the south east of England. The sample had a 50 per cent managerial/professional content as against 15 per cent in this group nationally. All had access to a WC, basin, bath and sink, with other appliances available to a less extent. This work, done over seven consecutive days in the middle of December 1987, showed that, as with the study reported above, appliances generally were used most frequently during the weekday morning peak, defined here as 07.30–08.30. The washbasin and the WC in particular were most used in this period, with sink use more uniformly distributed throughout the day. Weekend use generally was more uniformly distributed and less onerous. It was, therefore, recommended that data for a weekday peak should continue to be used for practical design. Table 1.3 summarizes the main numerical ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Water use, load and storage estimation

- 2 Requirements and regulations for water

- 3 Water installations

- 4 Principles of soil and waste pipe installations

- 5 Design of soil and waste pipe installations

- 6 Solid waste storage, handling and recovery

- 7 Rationalization of services

- 8 Fluid flow principles and studies

- 9 Unsteady flow modelling in water supply and drainage systems

- 10 Noise

- 11 Water conservation

- 12 Soil and waste drainage underground

- 13 Rainwater drainage

- 14 Plastics and their applications

- Appendix 1. Notes on Standards

- Appendix 2. Notes on sizing storage and piping for water supply

- Notation

- Bibliography

- Index