1: INTRODUCTION: CONFLICT AND CONSERVATION

Architectural structures which because of their specific technical features frequently survive for centuries, belong to the basic monuments of the past and the cultural development of the entire nation. At the same time they are evidence of its economic and social development. The works of architecture and town planning thus embody the history of the people that created them.

(Adolf Ciborowski, 1956)

INTRODUCTION

This introductory chapter sets out the dilemma at the heart of this book. There is a widespread agreement that urban areas must change, or they will stagnate. Yet, at the same time, there are growing pressures for preservation from both the general public – or, at least, an educated and vociferous minority – and from increasing elements of the design and planning professions. For the most part, Western cities are creations of the capitalist order, where investment fuels an economy and becomes part of the cycle of wealth creation. This capitalist imperative runs counter to the set of values based on aesthetic, environmental, non-quantitative criteria. So there is a clash of values: land and property exploitation for capital gain versus consideration of art, aesthetic and historical appreciation. There is also, in aesthetic terms, an essential tension between the old and the new, the familiar and the unfamiliar (Figure 1.1). This heightens our reactions to, and colours our enjoyment of, urban landscapes as with other fields of aesthetic endeavour. There is tension, too, between the uses of heritage to legitimate socio-political positions and conflicting ideologies of dissenting groups; hence the targeting of élite architecture to represent the national identity, and the targeting of those same structures for demonstrations or destruction. It is the nature and scale of this conflict which are major problems, remaining unresolved in theory – for there is no generally accepted theory of how to manage urban landscapes for conservation – and practice – as many post-war buildings in historic areas demonstrate. But the production and management of the changing urban landscape are processes in which conflicting ideologies are deeply embedded, and the common depiction of tension as a simple dichotomy of retain or redevelop is a gross over-simplification

Figure 1.1 Visual contrast: tension in the urban landscape: Swansea Castle and overshadowing office block (author's photograph)

The production and maintenance of the physical fabric of the urban environment absorb a large amount of the wealth of the Western world, and have done so for centuries, giving rise to the historic compositeness of many urban landscapes. Furthermore, a strong case has been made for the social, cultural and psychological significance of the townscape. Many studies show the need, in these terms, for the preservation of historic townscapes, in outward appearance at least. Economic reasons for preservation also exist and while practically strong, they are not intellectually as compelling as these other reasons. Substantial planning problems arise as townscapes age and as the social and economic conditions under which they were created change. Buildings become structurally, functionally and economically obsolete.

Adaptation of the townscape becomes necessary, but this is hard to achieve without some wastage of the investment of previous societies. During periods of great capitalist investment and development in property (for example the 1950s and 1960s in many Western countries) such wastage received relatively little consideration, pressures were high on historic sites, and the philosophy of ‘comprehensive redevelopment’ was dominant. At other times, for a variety of socio-cultural reasons, the conservationist ethic will be dominant. For example, interest in conservation in the Western world is at its highest for a century, and this can readily be demonstrated for the UK. In addition, increasingly the reality of urban development in Western societies is about the re-use of urban sites inherited from previous generations. Some two-thirds of residential developments in south-east England, for example, are within existing urban areas. This marked change of attitudes has helped to highlight the problem of accommodating the requirements of previous societies within the townscape legacy from previous generations.

There is thus a multiple problem. First, what is to be preserved? Closely allied to this is the question of who identifies the preservation-worthy buildings and areas, and whether this identification meets with the approval of the population living, working and recreating in these areas. Indeed, as a second facet of the problem, to what extent do those influencing development and those affected by it have consistent views about the area in which development is proposed? Thirdly, how is conservation/preservation to be carried out: are the buildings and areas identified in any way removed from the natural life-cycle of construction, use, obsolescence, decay and demolition? Fourthly, what is the nature and scale of changes proposed and carried out to the physical urban fabric? These are the questions addressed throughout the main body of this book.

How can this problem best be examined? Recent research in the UK has demonstrated the importance of a grouping of those involved directly and indirectly with change, the ‘agents of change’. Those directly involved are principally the owner, developer and architect; those indirectly involved include those affected by and commenting upon changes (neighbours, the public, local amenity societies); those making the decisions are the professional staff and elected representatives of the planning authority. In the UK there are two tiers of decision-making: the Local Planning Authority (LPA), usually the District Council, and central government, represented in England by the Department of the Environment (DoE). The manner in which these agents of change inter-relate is crucial to the outcome on the ground. This book draws upon a growing body of research dealing with these agents of change, their characteristics, interactions, and the outcomes in a variety of historic townscapes.

The book deals deliberately with UK examples for the bulk of its argument, for it is here that much of the detailed morphological research has been carried out, and here where there is a long-established legal-administrative system to promote conservation. Many key concepts of conservation have, since the mid-1980s, been tested in court. Some cases have even reached the highest court in the land, the House of Lords; so the legal interpretations of conservation-related actions and duties are well argued. Illustrations and examples of other systems, derived from other cultures and experiences, are used wherever appropriate. The concept of conservation used here is also deliberately restricted. As will be shown in this chapter, psychological and aesthetic arguments form some of the key justifications for conservation; both professional and public attention is often directed principally at the external appearance of structures and areas. This fits well with the ‘townscape’ tradition in UK planning thought, although this emphasis on the visual aesthetic is rather different to some other national approaches (cf. Bandini 1992). In this way, this investigation uses micro-level examinations of activities in conserved districts to address the multiple questions posed above. Large-scale changes affecting the historic or architectural character of preserved areas or buildings are significant, but so, too, are the myriad individually small-scale changes that may have significant cumulative impact. Changes to conserved structures, to structures not specifically conserved but which are within designated areas, and the design of wholly new structures are all significant in this exploration of the visual/ aesthetic impacts of conservation.

ARGUMENTS FOR CONSERVATION

The growth in public support for conservation, and its increasing enshrinement in planning legislation throughout the developed world, may owe much to a growing awareness of basic reasons for conservation, and an examination of recent literature suggests that psychological, didactic, financial, fashion and historical reasons are of greatest significance.

Psychology and conservation

In his all-encompassing examination of civilisation, Lord Clark (1969) suggested that civilisation could be defined as ‘a sense of permanence’, and that a civilised man ‘must feel that he belongs somewhere in space and time, that he consciously looks forward and looks back’. Various studies in environmental psychology, particularly those of P.F. Smith (1974a, b, 1975, 1977), strongly suggest that this ‘looking back’ is psychologically very important: even, perhaps, a necessity. There is a human need for visual stimuli to provide ‘orientation’ – the observer's awareness of his or her own location in a given environment – and ‘variety’ (Lozano 1974). These needs are met, in part at least, by historical areas that have survived relatively unchanged, providing symbols of stability: ‘the visual confirmation of the past provides a fixed reference point of inestimable value’ (P.F. Smith 1974a: 903). Historical areas act as cushions against Toffler's concept of ‘future shock’ (Toffler 1970). In a wider context, Lowenthal (1985) used a detailed presentation of minutiae and ephemera to support his relating of ordinary everyday experiences to the need for some tangible ‘heritage’. Not content with expressing this need, he also showed in some detail how we use the heritage and shape it to our own ends.

There is some empirical evidence to support this theoretical work. Taylor and Konrad (1980), for example, constructed a scaling system to measure the dispositions of people towards the past, and found strong sentiments in favour of conservation and heritage. Morris (1978) analysed reactions towards slides of different types and ages of buildings, finding that contemporary buildings are dismissed as discordant intrusions, while mediaeval buildings in particular, and classical styles to a lesser extent, possess considerable historical and architectural interest. Holzner (1970) gave an interesting description of conservation in practice in post-war Germany. He noted that after wartime destruction of over one million buildings, every effort was made to repair as many of the old buildings as possible and to reconstruct them in the inherited manner. Holzner concluded that this (and, by implication, any) preservation was not rational, but that a popular social need overcame rational approaches to post-war reconstruction. This appears to be a practical and large-scale demonstration of the psychological argument for conservation, which may also be applicable in other countries, such as the case of the post-war rebuilding of Polish towns.

Many of the psychological arguments are well summarised by Hubbard (1993) in a review of behavioural research and conservation attitudes. He suggests that the conservation of the familiar is of value in, for example, stabilising individual and group identities, particularly in times of stress. However, experimental psychology has shown that although familiar townscapes and buildings are highly rated, so too are some modern structures. Further, sample groups have also shown profound ambivalence towards the historicity of townscapes and buildings: in some cases, it is outward appearance only which was perceived to be important. Hubbard also warned that perceptions of place and conservation vary between groups of different socio-cultural backgrounds: the valued landscapes of one group may thus represent different things to another, and ‘the increasing fragmentation of British society exposes the inadequacy of conservation of traditional national and local cultures’ (Hubbard 1993:370). The same is true of any multicultural society. This introduces the concept of ‘heritage’ into the conservation argument.

Didactic: teaching, learning and conservation

The notion that there is a moral duty to preserve and conserve our historic heritage, to remember and pass on the accomplishments of our ancestors (Tuan 1977:197), is a common argument. The main reason underlying this moral duty appears to be pedagogic: the physical artifacts of history teach observers about landscapes, people, events and values of the past, giving substance to the ‘cultural memory’ (Lewis 1975). However, Faulkner (1978) showed that the historical heritage can be divided into the heritage of objects and that of ideas, with the implication that one may be conserved without the other. ‘This inevitably leads us to the question of architectural design and whether we can . . . separate the design from the building, and claim the design as a concept has a separate existence from the stones of which the building is built’ (Faulkner 1978:456). If so, then the handing down of the heritage could easily be achieved by the comprehensive recording of buildings or areas. Preservation of the actual fabric becomes no longer an absolute necessity in original or rebuilt form.

Finance and conservation

It has long been recognised that at least some aspects of conservation can be profitable. Hence an increasing number of country house owners began opening houses and grounds as tourist attractions, beginning with the Marquess of Bath at Longleat in 1949. Indeed, Lord Montagu of Beaulieu wrote a book with the significant sub-title ‘How to live in a stately home and make money’ (Montagu of Beaulieu 1967).

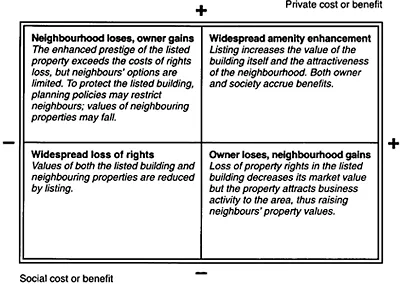

Yet because of the involvement of central and local governments in identifying structures and areas for conservation, and in imposing constraints upon owners, the economics of urban conservation become complex. Nevertheless, key issues of gains and losses can be represented quite simply (Figure 1.2).

While being property which is owned and managed like other real estate, government claims via ‘heritage tenure’ of its cultural quality, which it proposes to conserve for the public, contemporary and prospective, means that the owners of the property can only manage it subject to constraints. . . . But the costs of conservation are by comparison localised. They fall on the owners and occupiers of the property and also on the community of the administrative area in which the property happens to be.

(Lichfield 1988:201)

The key issues of the cost implications of conservation, and the nature, extent and distribution of gains and losses, can to some extent be assessed through standard techniques of cost-benefit analysis. Research for the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors took a qualitative view of the financial impact of listing buildings, and from interviews gave a series of reasons why such recognition of historic value may increase or decrease building value (Chartered Surveyor Weekly 1991:19) (Figure 1.3). However, political ideologies do distort considerations based purely on financial data, raising issues such as the following conflicts:

owners of heritage property should not be denied the rights available to others, so that any loss incurred should be compensated by the rest of the community; but where this loss is accompanied by increase in value to other owners, a betterment charge should be levied, to offset the burden on the rest of the community;

since the benefit is for posterity, the community finding the compensation should be that of the future, so that the cost to the contemporary generation should be met out of long-term loans to be paid off by future generations.

(Lichfield 1988:209–10)

Figure 1.2 Gains and losses in a financial analysis of conservation (adapted from Scanlon et al. 1994)

In practice, these dilemmas are little addressed. More practical considerations are more influential. For example, much impetus was given to conservationists by the 1973 oil crisis and subsequent concerns for energy efficiency. Local groups campaigned against numerous demolitions on the grounds that buildings were capable of economic re-use. However, at that time, mainstream economic arguments centring on the functional efficiency of maintenance, layout and adaptability dominated. Older buildings were expensive to restore and maintain, and could not provide accommodation to contemporary standards (Dobby 1978).

Attitudes have now shifted further towards the ‘green’ arguments. The concept of ‘embodied energy’ is now more widely accepted: calculating the energy cost of building an existing structure and modifying it, compared to the energy cos...