![]()

PART I

THE DEVELOPMENT CONTEXT

![]()

1 Introduction

Places matter

In 2009, the then UK Government published its strategy for improving place quality. This declared that ‘Good quality of place should not be seen as a luxury but as a vital element in our drive to make Britain a safer, healthier, prosperous, more inclusive and sustainable place’ (UK Government 2009: 2). The document set seven strategic objectives:

• to strengthen leadership on quality of place at the national and regional level;

• to encourage local civic leaders and local government to prioritise quality of place;

• to ensure relevant government policy, guidance and standards consistently promote quality of place and are user friendly;

• to put the public and community at the centre of place shaping;

• to ensure all development for which central government is directly responsible is built to high design and sustainability standards and promotes quality of place;

• to encourage higher standards of market-led development;

• to strengthen quality of place skills, knowledge and capacity.

Although published towards the end of the life of a Labour Government that had by then dominated British political life for the previous twelve years, the strategy reaffirmed messages from the Urban Task Force (1999), the Sustainable Communities Plan (OPDM 2003) and other earlier documents that place-making is as important as plan-making. It also echoed the call of Sir Michael Lyons (2007), in his wide-ranging review of local government, for place shaping in its broadest sense to be at the heart of local council concerns.

Since evidence from Europe (see, for example, Cadell et al. 2008, PRP et al. 2008) pointed to a stronger culture and practice of place-making on the Continent, the strategy generated important questions around the purpose and effectiveness of long-standing British approaches to managing spatial change. By that time, however, the UK economy was in severe trouble after more than a decade of continuous economic growth, and those involved in the development process were concerned more with their own survival than with the creation of great places for the future. It was therefore not the best time to make the perfectly reasonable claim that ‘Good quality development does not have to be more expensive than poor quality – and in the longer term the savings will be significant’ (UK Government 2009: 2). Within a year, the Labour Government had left office, to be replaced by a new coalition of parties with a very different agenda. A wave of public service cuts then threatened the capacity of local authorities to deliver even basic services, let alone place transformation, with Britain heading towards an era of economic austerity.

The main message of this book – that places matter and that shaping places is an essential governance activity – is not necessarily one that appears to match the state of Britain in 2012. Yet, the issues addressed here are so fundamental to delivering long-term sustainability that, in reflecting on recent experience, it is important to put down markers that can inform policy directions and likely achievements in the years to come. How place is interpreted and managed is crucial to balancing economic prosperity, social cohesion and environmental protection, which will become increasingly central to the task of governments over coming decades. Indeed, global concerns around climate change, rapid urbanisation, peak oil and economic restructuring put urban management among the most pressing issues likely to face governments of the future.

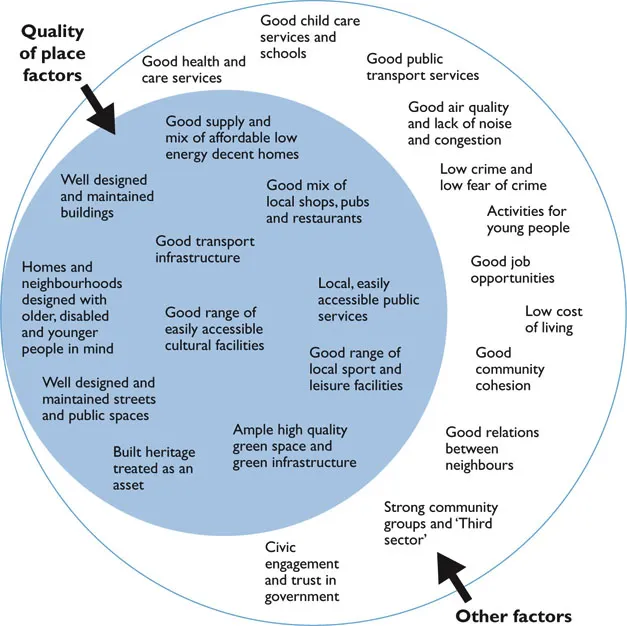

As Figure 1.1 shows, the factors that constitute ‘quality of place’ at the local level make a significant contribution to what might be construed within a broader understanding of the quality of life. As place is multi-dimensional, it is essential to emphasise that its physical and environmental characteristics are important in their own right, while also providing a platform for effective social and economic interaction. Moreover, if planning is about ‘promoting ways to advance the live-ability and sustainability of daily life environments, not just for the few but for the many’ (Healey 2010: 20), it becomes important to consider all its various dimensions, including the economic, within the broader concept of human flourishing in a sustainable context.

FIGURE 1.1 Local area factors contributing to good quality of life.

(UK Government, 2009)

Indeed, a host of debates around, for example, access to employment opportunities, educational achievement, neighbourhood quality, service delivery, mobility and community safety have consistently shown that place matters. This is why ‘The way places and buildings are planned, designed and looked after matters to all of us in countless ways. The built environment can be a source of everyday joy or everyday misery. It is an important influence on crime, health, education, inclusion, community cohesion and well-being. It can help attract or deter investment and job opportunities. Planning, conservation and design have a central part to play in our urgent drive to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and protect biodiversity’ (UK Government 2009: 2).

The purpose of this book is not to delve into each of those debates in any detail but, rather, to explore the process by which more successful places can be delivered, especially in a physical and environmental sense. This focus acknowledges the importance of the social and economic, while concentrating on what can reasonably be covered in a text of this length. Although the conception of place presented here is inevitably part of a broader picture, it is important enough to deserve clear focus. By reflecting on recent experience in shaping places, both within and well beyond the UK, the book aims to speak to those who, in the years ahead, will be centrally involved in such activity.

The search for future policy solutions is likely to prompt a fundamental reappraisal of how governments should seek to shape places and of how this will influence those beyond government whose impact on place is equally important. This highlights the importance of state–market relations, since places of real quality are generally delivered neither by the state nor by the market alone, but by some form of interaction between them. We argue that the nature and effectiveness of this interaction is at the core of understanding how places change over time and how they might be delivered more successfully.

Some schooled in the British hierarchical mode of governance (see Chapter 6) may well regard our interest in markets as indicative of a neo-liberal approach that has created places simply to satisfy the demands of the well-off, while ignoring the needs of those with limited market power. Yet, because the poor and the less mobile are often those most trapped by poorly designed and poorly integrated environments, creating well-designed and inclusive places is as much about social justice as it is about economic prosperity or environmental sustainability.1 Those who really delve into the book will therefore find strong criticism of what has come to be known as ‘market-led planning’ and discover instead something of the theory and practice of ‘plan-shaped markets’. Our essential argument is thus that effective place-making involves a style of market engagement in which city authorities are sufficiently skilled and knowledgeable to turn real estate markets to their advantage in seeking to create the kind of places in which the many can live, work or enjoy themselves. We now explain how this argument develops, as we outline the main themes of the book.

Themes of the book

Four main themes are explored in this book. The first investigates what makes places successful and, by implication, what makes them less than successful. This takes centre stage in the next chapter, which identifies five characteristics of successful places. Specifically, these highlight the importance of people to place, of connectivity and permeability, of variability in use and form, of local distinctiveness, and of sustainability, resilience and robustness. These characteristics have considerable potential to make places more valuable, not only in a narrow financial sense but also in relation to their broader social, cultural and environmental attractiveness.

Illustrations throughout the book draw attention to specific places of varying success. One of the main concerns has been to highlight lessons that can be learnt more generally from successful places, especially those in Europe and the UK that are considered by many to be exemplars. Among such case studies presented are those developed by a far-sighted landowner (Newhall), an active municipality (Hammarby-Sjöstad) and a government agency (Upton). These experiences are used later on in the book to help to establish what is involved in ‘the place production process’ (see Chapter 11).

Such valued places can be contrasted with what we term ‘default urbanism’ – the kind of second-rate places that emerge spontaneously, when no one has consciously tried to do better. Here, we emphasise the lack of collective thought and action that tends to intensify the risks of development activity and produce more disintegrated outcomes across both time and space. Unfortunately, many people’s everyday experience of place is represented by default urbanism, to the extent that those fortunate enough to live or work in more successful, sustainable or attractive places are considered the exception.

The contrast between successful and less successful places prompts us to explore how places come about, which is the second theme explored in the book. To understand the varied ways in which places originate, grow and evolve, we need to explore how the concept of place has been commodified, parcelled up and traded both as a financial asset in its own right and as the basis on which to exploit other economic opportunities. To investigate this, we analyse real estate markets, values and development processes in Chapters 3 to 5. Crucially, we see these as both socially and economically constructed and as highly diverse in their operation over time and space. This makes it difficult to predict, let alone manage, the kinds of places that emerge from market operations. Even so, it is apparent that the distinctive nature of real estate coupled with the unpredictability of the development process reinforces the tendency towards default urbanism.

Our third theme therefore concerns the need for collective action in place-making, and specifically the importance of governance arrangements that can promote and deliver more integrated forms of development. Chapter 6 thus examines different approaches that can be, and have been, taken towards the governance of place. Significantly, we do not assume that government intervention in real estate development necessarily produces more successful places than would market processes left to their own devices. Indeed, Chapter 6 illustrates the potential for government failure with some notable examples of where government interventions, undertaken at the time with the best of intentions, turned out to produce places of exclusion and neglect, which had subsequently to be remedied at significant public expense. How governments participate in place-making is thus just as important as whether they choose to do so in the first place. Issues around place leadership, stakeholder engagement and delivering capacity, all of which we explore in Chapter 6, are indeed critical to the potential success or failure of government attempts to reshape places.

The final theme thus concerns the interaction between public policy and private initiative, or what we call ‘state–market relations’ in land and property development. Such relations matter because places develop in a way that reflects both the dynamics of real estate markets and the dominant mode of governance at the time of their production. Significantly, we start this analysis in Chapters 7, 8 and 9 not with public policy, but by looking in turn at the strategies, actions and interests of developers, landowners, funders and investors, primarily in the private sector. This reveals widespread diversity in their performance and highlights the contrast between entrenched and more innovative behaviour.

On that basis, in to 14, we review a range of relevant policy instruments, defined by their capacity to shape, compel, constrain or incite what market actors choose to do. This final theme thus emphasises that producing more successful places necessarily involves shaping, regulating and stimulating real estate markets, while building the capacity to do so.

The book views planners as market actors whose potential to shape the built environment depends on their ability to analyse and transform the embedded attitudes and practice of a range of other market actors. This challenges planners both to be skilled in understanding the political economy of real estate development and to be successful in influencing its outcomes. We trust that the four themes covered in the book will help current and future planners, wherever they work, to meet those challenges.

![]()

2 Successful places

Introduction

Places matter intensely to human experience. Where we live, and how far we can travel daily, conditions our personal activities and interactions. Alongside this, economic prosperity or reversal displays conspicuous expression in its differential treatment of different places. Increasingly, specific notions of place are invoked in confronting climate change, with more compact cities, for example, seen as central in reducing energy consumption and making development more sustainable. The social, economic and environmental importance of place thus makes it essential to understand why certain places appear to be more successful than others.

To answer this, some commentators point to the countless unconnected and spontaneous decisions of the real estate development process (see Chapter 5), which from time immemorial have fashioned cities as if by some physical equivalent of Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’. Yet others, well aware of urban history and political economy, know that places are also shaped by the powerful forces of state power and finance capital – sometimes conflicting with each other, but more often working in collaboration. Those who look can thus recognise a ‘visible hand’ that explains the way places develop. Too often, however, developments created by the visible hand of state power or finance capital have turned into places of exclusiveness and exclusion, showing how place can readily become a physical manifestation of prevalent power relations (see Figures 2.1 and 2.2).

FIGURE 2.1 Red Road Flats, Glasgow, Scotland. Built between 1964 and 1968, Red Road Flats once housed 4,700 tenants in eight tower and slab blocks. Symbolic of social exclusion and now occupied mainly by asylum seekers, the blocks will all be demolished by 2016.

(Amanda Vincent-Rous, used under the Creative Commons licence)

FIGURE 2.2 Gated community, River Run, North Tempe, Arizona, USA. Residents of the 112 homes behind these entrance gates enjoy wel...