![]()

1

Don’t Work Harder! Work Smarter!

BELLE WALLACE

We need thoughtful learning. We need schools that … focus not just on schooling memories but on schooling minds.… We need ‘a literacy of thoughtfulness’. We need educational settings with ‘thinking-centred’ learning, where students learn by thinking through what they are learning about.

(Perkins 1992: 7)

We can think of ‘smart schools’ … as exhibiting three characteristics: Informed. Administrators, teachers, and indeed students in the smart school know a lot about human thinking and learning and how it works best. And they know a lot about school structure and collaboration and how it works best.

Energetic. The smart school requires spirit as much as information. In the smart school, measures are taken to cultivate positive energy in the structure of the school, the style of administration, and the treatment of teachers and students.

Thoughtful. Smart schools are thoughtful places, in the double sense of caring and mindful. First of all, people are sensitive to one another’s needs and treat others thoughtfully. Second, both the teaching/learning and the school decision-making processes are thinking centered.

(Perkins 1992: 3)

PURPOSE

More than ever before, schools are aware that they need to work ‘smarter’ rather than ‘harder’ for two fundamental, common-sense reasons. Firstly, the daily demands on teachers mean that there is very little energy left at the end of the day to work any harder! Secondly, we are well aware that dealing with current living and working conditions requires thinking skills and problem-solving abilities, so that we can become smarter at coping with the increasing complexities that bombard us.

Hence the purpose of this text is not to suggest ‘yet another initiative’ that we must take on board, but to engage in a reflective audit of what we already do well, and then to consider ways of extending our good practice. This book is the second in a series based on the development of thinking and problem-solving skills across the curriculum (see Wallace 2001). The generic principles of working in a thinking skills paradigm are essentially the same, hence some of the core diagrams and teaching principles are repeated in this first chapter; but the application of the principles will be different for each Key Stage. Each subsequent chapter will focus on topics and activities relevant to learners at the end of Key Stage 2 and the beginning of Key Stage 3. There is a special reason for this emphasis: namely, the national concern over the apparent ‘dip’ in pupils’ achievement as they move from one Key Stage to another. Transition from one stage of schooling to the next always needs to be effected carefully and thoughtfully, but the transfer from primary to secondary school is particularly problematic with regard to continuity and avoidance of repetition.

The writers thought that in looking at middle schools we could show the transition from the more ‘generalist’ teaching common in the primary phase to the more ‘subject specialist’ approach in the early secondary phase. In addition, using examples of pupils’ work we could show the level of challenge that Year 7 pupils can manage. However, this is not to ignore the difficulty that secondary schools face when beginning to work with pupils from a wide range of feeder primary schools. To ease the discontinuity between Key Stages 1 and 2, many secondary schools are developing stronger working links with the primary phase: detailed portfolios of pupils’ work are being passed on to secondary phase teachers and the assessment of primary pupils’ levels of achievement is comprehensive and informative, making it easier for Key Stage 3 teachers to effect a smoother transition of pupils emerging from Key Stage 2.

We would emphasise, however, that the most important factor in easing the dichotomy between Key Stage 1 and 2 lies in schools working within a thinking-skills framework. This inevitably creates greater opportunity for differentiation of lesson activities, since the thinking-skills paradigm embedded in this text essentially means that teachers and pupils work together to identify appropriate and varying starting points for groups of learners.

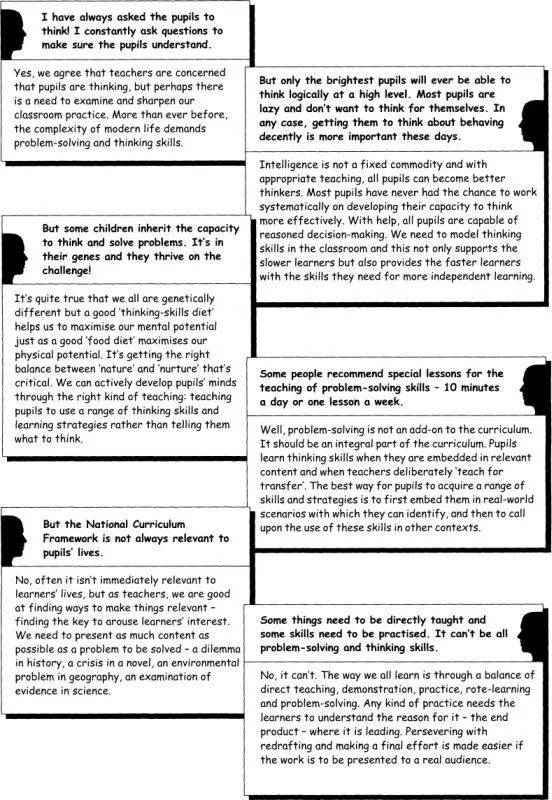

GROUP DISCUSSION

It is important to clarify the thinking-skills rationale that underpins the approach used throughout this text. The comments opposite and overleaf were raised by teachers during discussion on INSET days across the country. Reflect on this discussion and discuss any additional questions you think of with a group of colleagues.

What do you think?

REFLECT

Teachers have always been concerned that learners were ‘thinking’, but there are a number of perennial problems that plague us as teachers. Let’s reflect on these.

The National Curriculum Framework encompasses a massive amount of content that must be covered in a certain time.

We agree – The content in the National Curriculum Framework is extensive,

but – a great deal of it is very repetitive and many learners repeat skills and content they have already mastered. If we can reduce the amount of unnecessary repetition, then we create more time for using the content in a problem-solving way.

There are specific subject skills and strategies that we need to teach and demonstrate and this can’t always be done in a problem-solving’ way.

We agree – Demonstration, whole-class teaching and rote-learning are important learning techniques,

but – we need to give the pupils the reasons why we use these techniques, and then embed what the learners are learning in a problem-solving exercise as often as is possible.

I need to repeat things often because learners don’t remember.

We agree – Learners do need to ‘revisit’ ideas as a base for further extension and they also need to practise skills in order to perfect them,

but – if we spent more time encouraging learners to reflect upon and consolidate their initial learning, then they would mentally crystallise what they had learned and would be able to recall it more easily.

We need to repeat things because learners don’t transfer knowledge and skills from one subject to another.

We agree – Transfer of knowledge and skills across subjects is a perennial problem,

but – transfer of knowledge and skills does not happen automatically. We need to consciously teach for transfer and help learners not only to see the cross-curricular links, but also the links with everyday life.

COMMENT

Recently, there has been the realisation in national government that the National Curriculum Framework needs to emphasise the importance of the development of problem-solving and thinking skills across the curriculum. It is apparent that many pupils are failing to reach the higher levels of achievement, especially the more able pupils who should be attaining the highest levels (Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted) 1994). Memorisation of content is not enough: the highest levels of achievement require problem-solving strategies and the thinking skills needed for dealing with higher order questions. To address this need, teachers across the country are regaining the confidence to address the process of the curriculum alongside the content.

However, the writers stress that ‘problem-solving and thinking skills’ are not just for very able pupils: ‘When the fresh breeze of problem-solving and thinking skills blows, all leaves rustle.’ Teaching children a range of problem-solving strategies and thinking skills enables all pupils to learn more efficiently.

Undoubtedly, good teachers have always taught with the aim of developing pupils’ thinking skills, but this has often lacked coherence and consistency: and with the increase of administrative work and curriculum content, those teaching techniques that we all know are good practice have been pushed to one side. However, the climate is right for us to take stock of how we teach and to extend and consolidate existing good practice.

It is important to stress again that extending and consolidating a problem-solving and thinking skills approach across the curriculum provides the less able with a framework for the ‘mental scaffolding’ they need to develop their potential. The more able are equipped with a set of problem-solving strategies that enables them to work more independently on small-group or individual activities.

However, classroom activities that systematically develop thinking encourage and promote greater differentiation of pupil response: but when the ethos of the class is that everyone matters and can contribute to the whole, then it is acceptable to show different strengths and weaknesses.

Theoretical background to the model of problem-solving and thinking skills used throughout this text

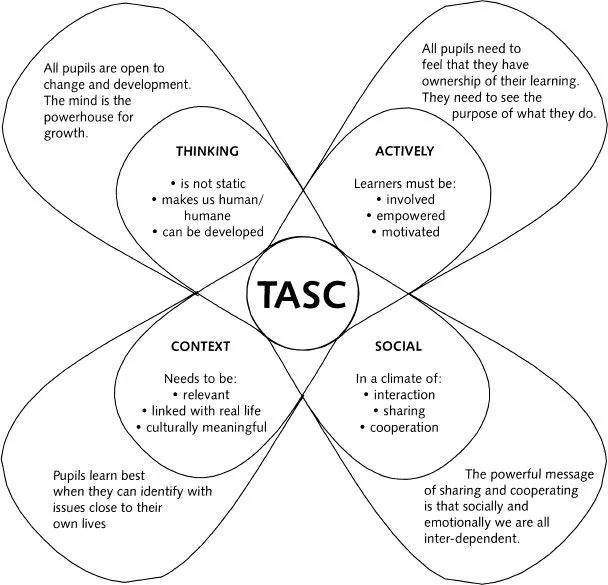

In the mid-1980s, Belle Wallace and Harvey B. Adams surveyed the main thinking-skills packages that were already published and they visited key areas in the world where there were major thinking skills projects in operation. Then, adopting an eclectic approach that embraced the most successful elements of the range of thinking skills projects they had evaluated, they conducted an action research project with groups of disadvantaged learners and their teachers over an intensive period of ten years. Strategies and methodologies were trialled, evaluated and reflected upon by the researchers, the participating teachers, a group of educational psychologists and, importantly, the pupils. The key to the success of the action research project lay in the quality of the reflection, consequent rethinking and trialling of the thinking skills and problem-solving strategies being used. This process culminated in the publication of TASC: Thinking Actively in a Social Context (Wallace and Adams 1993), which sets out a generic framework for the development of a thinking and problem-solving curriculum.

The major t...