![]()

CHAPTER 1

Your Place and/or My Place?

Jeffrey Hou

In cities and regions around the world, movement and migration of people have continued to shape the makeup and making of neighborhoods, districts, and communities. In North America, new immigrants have played a critical role in revitalizing many decaying urban landscapes, creating new and renewed cultural ambiance and economic networks that transcend borders. In Seattle, for instance, Vietnamese businesses have transformed a declining urban area with vacant warehouses and storefronts into a vibrant commercial center at the edge of downtown. In Los Angeles, Latina/o immigrants turn front yards and streets into social gathering places and building façades into canvases for murals and cultural icons. In Richmond, BC, Canada, an Asian night market has become a major cultural event that draws visitors throughout the region and across the US/Canadian border. Across the Pacific, guest workers in Hong Kong transform the deserted office district in Central into a site of carnivalesque gatherings every Sunday. In Taipei, the Songkran Festival has become an annual event celebrated not only by immigrants, refugees, and foreign workers from Burma, Thailand, and Cambodia, but also by local residents and civic leaders.

While contributing to the multicultural vibes in cities, movement and migration have also resulted in tensions, competition, and clashes of cultures between old-timers and newcomers, employees and employers, and individuals and institutions. In Los Angeles, Korean and Bangladeshi immigrant communities competed over the official naming and recognition of their overlapping neighborhoods (Jang 2009). In Brazil, Chinese employers and local workers clash over work ethics and lifestyles (Brooks 2011). In Taipei, migrant workers are often harassed by police and portrayed negatively in the media as threats to law and order. In North London, the fatal shooting of an African–Caribbean by the police led to days of rioting across different cities in Britain in Summer 2011. These recurring conflicts illustrate the profound challenge of increasingly diverse populations in contemporary cities.

As cities continue to serve as the main destination of transnational and intranational migrations, what role can they play in supporting the growing diverse populations? How can urban places function as vehicles for cross-cultural learning and understanding rather than just battlegrounds and turfs? How can cross-cultural interactions be constructed, enabled, or “staged” through social and spatial practices in the contemporary urban environment? As migration, diasporas, and translocality have further destabilized existing meanings and identities of places, how can we re-envision placemaking in the context of shifting cultural terrains? These are the questions and challenges that we intend to investigate in this book.

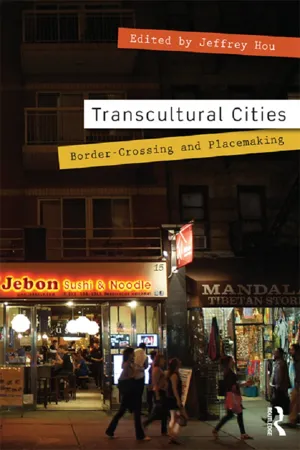

Figure 1.1 Grocery markets in Seattle's Little Saigon brought new economic vitality to an area that has long been dormant at the edge of downtown. Photograph by Jeffrey Hou.

Rise of New Multicultural Cities

Movement and migration has long been a central characteristic of civilization and human settlement (see Appadurai 1990; Hall 2000; Wood and Landry 2008). This was how Polynesians managed to settle in the countless islands and archipelagos throughout the Pacific, and how historic cities such as Rome and Xian, and megalopolises today such as New York and Tokyo, came to being. In the decades since World War II, advancement in transportation and communication coupled with economic globalization, along with conflicts and large-scale natural catastrophes, have accelerated movement and migration of people (Castles and Miller 2009). In 2010, the population of international migrants was estimated at over 213 million, or 3.1 percent of the world's population, compared with 76 million in 1960 (UNDESA 2011; UNDESA 2005, cited in Castles and Miller 2009). In the United States, the estimated number almost doubled from 23.3 million in 1990 to 42.8 million (13.5 percent of total population) in 2010 (UNDESA 2011).

Figure 1.2 El Pedorrero Muffler Shop in East Los Angeles: a case of self-made neighborhood transformation. Photograph by Jeffrey Hou.

Collectively, these movements and migrations have resulted in fundamental changes in global political, economic, and social and cultural systems (Roseman et al. 1996). Demographically, for example, international migration has increased ethnic diversity in immigrant-receiving countries (Castles and Miller 2009). Furthermore, in many North American and European cities, the new ethnic diversity is not limited just to the traditional sites of settlements in core downtown areas, but is instead widely dispersed to the suburbs, creating a complex patchwork of new ethnic enclaves (see Qadeer 1997; Krase 2002; Li 1999). Similarly, it was observed that the patterns of migration have diversified to include intra-regional migration within and between the Asia-Pacific, Latin America, and Middle East (Castles and Miller 2009). In terms of social and political consequence, Holston (1998: 51) argues “as new and more complex kinds of ethnic diversity dominate cities, the very notion of shared community becomes increasingly exhausted,” and “the notions of formal citizenship” becoming increasingly problematic.

In recent writings on migration and urbanism, various terms and concepts have been proposed to illustrate these growing phenomena. Geographer Curtis Roseman and others (1996) used EthniCities to characterize cities with a variety of people having distinctive cultures and origins. Anthropologist Arjun Appadurai (1990: 7) suggests ethnoscapes to describe “landscapes of persons who constitute the shifting world in which we live.” Urban designer Noha Nasser (2004b) uses “Kaleido-scapes” to describe the landscapes of migrant groups as “a hybrid urban morphology that combines local vernaculars with global (or imported) elements.” Borrowing from Salman Rushdie, planning historian Leonie Sandercock (2003: 1) put forward Mongrel Cities to conceptualize the new urban condition “in which difference, otherness, fragmentation, splintering, multiplicity, heterogeneity, diversity, plurality prevail.”

But beyond simply concepts and descriptors, how can we develop a framework for not only understanding but also for actions that facilitate active making of space and places to engender diversity, hybridity, and cross-cultural learning and understanding? How can we as individuals and as designers and planners actively support the making of Mongrel Cities, ethnoscapes, and kaleido-scapes to better serve diverse communities? Before we launch into our proposed framework, it is useful to revisit some of the past and current attempts under the rubric of multiculturalism.

Multiculturalism and the Planning Challenges

In the late twentieth century, growing migration and new settlements have given rise to multiculturalism as a new cultural and institutional paradigm. In countries including Canada, Australia, the Netherlands, and Sweden, multiculturalism has been enshrined into social policies that recognize identities and equal rights of different ethnic groups since the 1970s (Castles and Miller 2009; Parekh 2000; Sandercock 2003). Specifically, the Canadian Multiculturalism Act of 1988 defines multiculturalism as a policy designed to preserve and enhance the multicultural heritage of Canadians while working to achieve the equality of all (Qadeer 1997). Significant spending has been provided to support “maintenance of various cultures and languages” (Sandercock with Brock 2009). At the city level, municipal governments in Frankfurt, Rotterdam, Vancouver, and several Australian cities have adopted multicultural policies to serve their diverse citizens (Sandercock 2003; Thompson 2003). In the UK, developed in the wake of racial riots in 2001, the community cohesion agenda has promoted “neighborly mixing as a means of tackling racism and problematic race divides” (Wise and Velayutham, 2009: 5). In the United States, the rise of multiculturalism reflects shifts in cultural discourses, as minority groups (defined by race, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality) question the long-standing norm and assumption of melting pot and seek recognition for their distinct cultural identities and practices—in what Cornel West (1990) describes as “new cultural politics of difference.”

In the field of urban planning and design, there has also been an awakening of sorts to the multicultural reality of today's cities (see Sandercock 1998a, 1998b, 2003; Burayidi 2000a; Qadeer 1997). Increasingly, planners and city administrators are being asked to develop cultural competency in working with diverse communities and constituents, as they are confronted with competing expectations about municipal services and patterns of urban growth (Pestieau and Wallace 2003). Sandercock (1998a: 16) argues that planners need to develop “a multicultural literacy more attuned to the cultural diversity, and to redefine and reposition planning according to these new understandings.” She further suggests that an open and communicative planning process is needed, which requires planners to have “life experience, communicative skills and, in multicultural or multiethnic contexts, cross-cultural understanding” (Sandercock 2000: 23). Similarly, Umemoto (2001: 17) argues that designing and facilitating planning processes to accommodate cultural differences requires planners to “extend their thinking into other epistemological worlds.” More than just an ethical responsibility, Burayidi (2000a) argues that multiculturalism has become practically necessary.

A number of planning approaches have been recognized or developed to meet the challenges of growing cultural diversity. For example, Sandercock (2000) sees Paul Davidoff's Pluralist Planning as a model to address the differential impacts of planning on race, gender, and class. Burayidi (2000b: 45) suggests Holistic Planning as “a means of social actions based on diversity, tolerance, and cooperation.” Ameyaw (2000: 101) proposes Appreciative Planning as a model based on mutual respect, trust, and care-based action, and “to create contexts in which planners and multicultural groups can continuously learn and experiment, think systematically, engage in meaningful dialogue, and create visions that energize action and inclusion in city planning.” In engaging the multicultural publics, Qadeer (1997: 493) notes that “the scope and procedure of citizen involvement in the planning process have to be modified to accommodate multicultural policies.” He calls for more flexibility in planning norms and practices in recognition of ethnic and social diversity (ibid.). Similarly, Hou and Kinoshita (2007) suggest informal mechanisms as an equally important tool for bridging social and cultural differences in diverse communities.

As commonly understood, multiculturalism posits that all ethnic groups in society should be able to exercise equal rights without having to give up their own culture, religion, and language (Castles and Miller 2009). In practice, however, multiculturalism and multicultural planning is far from being fully realized. While the discourse and institutionalization of multiculturalism has been important in reversing the predominant practice of assimilation, the actual outcomes in terms of embracing diversity, identities, and cultural differences remain highly contested. Planning scholar Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris (2002: 335) observes that ethnic minority neighborhoods are often described in negative terms by authorities “that wish to eliminate, control, or regulate them.” Similarly, Jacobs and Fincher (1998: 1) argue that “city governance has vacillated between celebrating and enhancing such diversity, on the one hand, and regulating and repressing it, on the other.” Sandercock (1998a: 164) notes that the multicultural city “is perceived by many to be much more of a threat than an opportunity.”

In many cities today, despite growing cultural diversity, the social and spatial barriers between different ethnic groups have persisted. In North America, as immigrants increasingly move to the suburbs, so have the racial and ethnic lines that commonly delineate the inner city (Talen 2006; Krase 2002). Using the Chinese takeaway in London as an example, Parker (2000) wrote about the unequal terms of exchange between European and Asian in both past and present. In cities such as Tokyo, Taipei, and Seoul, migrant communities are largely invisible and unrecognized in the everyday landscapes and the cities’ social policy. In many European countries, immigrants and refugees are largely confined to the outskirts of cities, creating pockets of concentrated poverty and joblessness, setting the context for negative perception of these communities. In Paris and other French cities, these pockets of migrant settlements became sites of a series of civil unrest in 2005.

Figure 1.3 Except for a few businesses and weekend gathering, the Filipino guest workers remain largely invisible in Taipei. Photograph by Jeffrey Hou.

As institutionalized social policy, multiculturalism has been challenged by critics of different ideological orientations. Hall (2000) notes that multiculturalism has been contested by the conservative Right as well as the liberals, for threatening the cultural purity of the nation on the one hand and the universalism and neutrality of the liberal state on the other. Expressing a libertarian view, Welsh (2008: 16) argues that “racism and multiculturalism are forms of tribalism that promote separation of individuals based on racial, ethnic, and/or linguistic characteristics.” He states that, in the context of the United States “the sharp differentiation of ethno-racial blocs in culture and politics may function to reproduce elements of racist social patterns” (ibid.: 2). In place of multiculturalism, Hollinger (1995) suggests a “post-ethnic” perspective that favors voluntary over involuntary affiliations and promotes solidarity of people with different ethnic and racial backgrounds.

Facing the complexity of today's migration, movements, and social change, the model of multiculturalism seems no longer sufficient or adequate. Scholars such as Martin and Midgley (2003) argue that both assimilationists and pluralists have failed to grasp the dynamic reality of immigrants and immigration. Furthermore, as the boundaries of nation-states become more porous, Nasser (2004a) argues that the presence of transnational cultures presents a challenge to the traditional claims of citizenshi...