![]()

PART ONE

UNDERSTANDING ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOUR

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Human Resource Management (HRM) is founded on an understanding of all aspects of the management of people at work. In this chapter the significance of individual differences between people is taken as the starting point for those who wish to understand the ‘human’ part of ‘human resource management’. In an era when the main source of innovation and creativity is located in the efforts, imagination and application of people at work, there is increasing employer respect for the individual’s contribution. The search for talented people as a source of competitive advantage, and the need to find employees who will come to share the values of the organization, who will make a personal contribution, however menial, to their roles, have an important part in human resource strategy.

Almost all aspects of HRM require an appreciation of significant individual differences: understanding what is innate, what is learned, what can change, what motivates people, and what relationships may productively be formed. How to find, to reward, to develop and to elicit the best performance from individuals is very much the subject of HRM, and informs the understanding of relationships at work on a larger scale and provides insights into what constitutes the potential for high performance, and how to make teams and organizations successful.

PERSONALITY

In this chapter, we will take up this theme as the bedrock for the study of HRM. We begin with a consideration of a number of ways to understand individual differences by looking at the concept of ‘personality’. Personality is the term often used in everyday language to describe the individual characteristics of people.

When we are dealing with questions concerning individual differences it is useful to consider if we are discussing differences in personality. According to Fonagy and Higgitt (1984: 2): ‘A personality theory is an organised set of concepts (like any other scientific theory) designed to help us to predict and explain behaviour.’

Many of the basic ideas about personality derive from early theorists in the psycho-analytic tradition, such as Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung and Alfred Adler. From Freud we have ideas about neuroticism and stability; from Jung theories about the traits that make up someone’s personality, and from Adler the notion of complexes, such as the inferiority and the superiority complexes. The theories are intended to be logical frameworks for integrating observations about people, and should help to produce new ideas to explain and understand behaviour. Personality theories describe the characteristic ways in which individuals think and act as they adjust to the world as experienced. These include genetic and unconscious factors, as well as learned responses to situations. Often personalities are described as a series of ‘traits’.

Carl Jung defined the personality traits that emerged from his ideas in this theory of individual differences, chief amongst which were the overall attitudes of ‘extroversion’ and ‘introversion’. These traits help to explain how an individual sees and understands the world, how the person processes information and makes decisions, which depends, Jung argues, upon the person’s thinking, feeling, sensation and intuition. These ideas have been popularized by the widespread use of the Myers Briggs inventory in occupational guidance, management development and career development.

In HRM, questions about the appropriateness of ‘specific traits’ or attributes are frequently raised in selection and assessment decisions. We discuss psychometric tests later in the book, but we should note here that researchers have identified a variety of personality traits (McRae and Terracciano 2005). There is evidence that the many individual-specific traits, such as ‘warmth’ or ‘unreliability’, can be subsumed under what are known as the ‘Big Five’ dimensions of personality, these being extroversion, neuroticism, agreeableness, conscientiousness and openness to experience.

These dimensions can be defined as follows:

1 Extroversion: extroverts tend to be sociable, relate themselves readily to the world around them.

2 Neuroticism: neurotics view the world as a frightening place. Neurotics have anxieties and are self-conscious.

3 Agreeableness: the ability to care, to be affectionate.

4 Conscientiousness: careful, scrupulous, persevering behaviour.

5 Openness to experience: these people have broad interests and are willing to take risks.

These attributes are scales in themselves, for example, extroversion–introversion, neuroticism–stability, and the balance will be a mixture of positions for any individual, along the five continua.

Many researchers such as Raymond Cattell have emphasized that the attributes of our personalities are not totally fixed. On the contrary, we are able to adapt and to change according to the situations we face, although it is anticipated any changes in behaviour would be consistent with our personality overall.

INTELLIGENCE

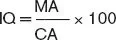

Some of the criticisms of ‘personality traits’ theories are that these theories imply an embedded set of behaviours, and that traits are described as absolutes, rather than in degrees, and can also be directed against the concept of intelligence. Where the idea of measurement did take hold, there was also the problem of the precise numbers produced being understood popularly as absolute facts. Measures such as a person’s ‘intelligence quotient’, which was originally a measure of development in children in the early part of the twentieth century, suggests a ‘scientific’, technical way to measure intelligence, through the measure:

where MA = mental age of the child, and CA = the chronological age of the child.

Very often, HR staff are asked by line managers in recruitment activities whether or not a prospective employee is ‘intelligent’ or not, for example. Just as personality is neither constant nor simply a group of independent traits, intelligence must be judged according to the environment in which the person is being asked to demonstrate it. There is also a view that there are different kinds of intelligence.

Early theorists proposed that there were two factors – general intelligence and special abilities. In the 1920s Spearman proposed that people who possessed good general intelligence (G), often also have special abilities. This line of research has continued, so that Thurstone (1938) believed there were seven factors that described intelligence, including verbal fluency, numbers, memory, speed of perception and spatial visualization. By 1973, Sternberg was considering the importance of cognitive processing as an aspect of intelligence. Howard Gardner (1983) is a modern theorist who has set out a theory of multiple intelligences (MI). He argued there were seven: linguistic, logical-mathematical, spatial, musical, bodily-kinesthetic, interpersonal and intra-personal. He later added existential intelligence (covering knowledge of self) and naturalist intelligence.

Philip Vernon and other researchers concluded that intelligence is best seen as a hierarchical model. This follows Spearman’s ‘G’, as being capable of being broken down into a number of major factor groups, which can be further divided into minor group factors. One conclusion that can be drawn is that intelligence measurement should therefore take account of ability in many fields, not just the IQ test, numerical, logical and linguistic abilities.

Aspects of intelligence are often contained in the attributes measured by the various personality tests. For the HR practitioner, these tests are useful guides in selection, talent management and decisions on promotion, but they are only a guide (see Chapter 11). Whatever analytical perspectives are applied, the important considerations are that the person is considered as a whole individual, not merely as a collection of disconnected attributes.

Emotional intelligence is of the utmost importance in many types of work. There is a need for ‘emotional labour’ in work that has a personal service element, for example in sales roles, airline flight attendants, and in retail work. At a deeper level, this is taken for granted as a part of some professional roles, where emotional intelligence (EI) is combined with experience, gained over many years, in roles such as school teachers, nurses, and in the legal profession. Many senior managers would also say this is essential in any leadership role.

It is especially important for human resource managers who necessarily spend much of their time listening to the views, proposals, problems and complaints from line managers and their subordinate staff. These aspects of their work also require emotional competencies. This is significant, owing to the expansion of the service sector of the economy: ‘Emotional intelligence refers to the capacity for recognising our own feelings, and those for motivating ourselves and for managing emotions well in ourselves and in our relationships’ (Goleman 1998: 317).

Intelligence quotient (IQ) and emotional intelligence (EI) are not in opposition, but are different sets of competencies. EI requires knowing one’s own emotions, managing emotions, motivating oneself, recognizing emotions in others and handling relationships successfully (Goleman 1996: 43). EI skills can be developed and those who possess such skills are more likely to be effective, having ‘mastered the habits of mind that foster productivity’ (Goleman 1996: 36).

GENERATIONAL DIFFERENCES

Changing demographics due to longevity and a lower birth rate in most developed economies are encouraging an understanding of the different mindsets of people who were born and educated and worked in different eras, but who are still active in the workforce. These are, of course, perceptions of generational differences.

The four different generations that were working together at the turn of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries created an unusual situation. These were described by the Society for HRM in the USA (2004) as in Table 1.1.

TABLE 1.1 CHARACTERISTICS OF FOUR GENERATIONAL GROUPS

Veterans | Plan to stay with the organization long term Respectful of organizational hierarchy Like structure Accepting of authority figures at work Give maximum effort |

Baby Boomers | Give maximum effort Accepting of authority figures at work Results-driven Plan to stay with organization long term Retain what they learn |

Generation X | Technologically savvy Like informality Learn quickly Seek work–life balance Embrace diversity |

Generation Y | Technologically savvy Like informality Embrace diversity Learn quickly Need supervision |

Source: Burke 2004.

These are very rough classifications, and there have always been generational differences, owing to the different perspectives of the young and the old, which may lead to stereotypical views of the young and the old. The counter to this view is to define generational differences in terms not so much of age, but of the shared social and economic experience in different epochs, affecting the lives of people born at different periods of time (Mannheim 1952). There is some evidence that the particular circumstances of different countries (for example in the Far East and in Europe) have created different attributes of the different generations (Parry and Urwin 2011).

For HRM, the significance of different generational values and sources of motivation could be a source of inter-organizational conflict. For example, the SHRM (2004) survey in the USA reported 24 per cent of HR professionals witnessing this conflict on a frequent basis (P2). However, differences between generations may also provide a valuable balance to work teams and points of contact with customers.

MOTIVATION

Motivation may be defined as an inner force that impels human beings to behave in a variety of ways and is, therefore, a very important part of the study of human individuality. Because of the extreme complexity of human individuals and their differences, motivation is very difficult to understand, both in oneself and in others. Nevertheless, there are certain features of motivation that may be regarded as generally applicable:

1 The motivational force is aroused as a result of needs that have to be satisfied. Thus, a state of tension or disequilibrium occurs that stimulates action to obtain satisfaction.

2 The satisfaction of a need may stimulate a desire to satisfy further needs (for example, ‘The more they have, the more they want’).

3 Failure to...