This is a test

- 512 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Market Revolution and its limits summarises why many economists believe that markets are best. It explores how even 'market failures' can be given market solutions, and asks why market ideas seem to have taken such a firm hold. Non-polemical in its approach, this book provides a comprehensive appraisal of the market and its alternatives, backed up with empirical international illustrations.

Shipman concludes that the 'revolution' lies in redefining the market process rather than the market outcome.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Market Revolution and its Limits by Alan Shipman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1 What markets are

The market is a means of social organisation—one way people can coexist while choosing varied routes to different personal goals. Other such means have been tried, most being regarded (at least for a time) as more legitimate organisational means with worthier ends. When social organising principles are allowed to compete, however, few have proved able to conquer or even hold their own against the market. Even those not persuaded by the elegant theories promoting the market’s efficiency properties have been forced to concede its resilience, sustained by individuals’ willingness to trade in it, with socialism resigning to market forces, and once-mighty governments and corporations submitting to market discipline.

Economists’ two-centuries-old claim that a free interplay of markets is the best way to allocate and expand a society’s material wealth is increasingly accepted as a simple truth, even as the theoretical explanations for its success grow more mathematically complicated. Interdependent groups of people can let their members choose and pursue their own objectives without exhausting the natural resources of the group, overloading (and corrupting) its political institutions or destroying its cohesion in a storm of incompatible demands.

Before examining the basis of these claims for the market and its progress in practice against other transaction types, some definitions are needed. The next section summarises the conventional microeconomic representation of a market. How such markets interact across space and develop across time are the subject of the next three chapters, after which an alternative characterisation of the market in information-processing terms is given in Chapter 5. This sets the scene for assessing alternative ways of conducting transactions, which are most easily characterised as more casehardened versions of the market ‘ideal type’.

1.1 The logic of individual transaction

The claim that markets play an unavoidable, and increasingly universal, role in social organisation has three main foundations: that market dealing is more natural, more non-discriminatory, and more capable of optimising scarce resources than any other means of allocation. This threefold contention of evolutionary fit, social justice and economic efficiency underlies the increasing depth and geographical extent to which market principles are now being applied.

Belief in the special properties of markets has also led to their adoption, both concretely and conceptually, far beyond the physical marketplace in which their workings were first observed and explained. The idea of markets for political programmes and social provisions, for natural landscapes and charitable contributions, for birth and marriage, even for ideas (and markets) themselves, has come to shape the way people think and act, in areas once regarded as well sheltered from dry cost-benefit calculation. Much of the world now finds it surprising that, only a short while ago, even the idea of labour, land and capital trading through markets was viewed with scepticism and suspicion. Markets’ rise to primacy in social organisation has two powerful components: a theory depicting it as the best means of harnessing and fairly sharing natural and human resources, and experience which seems to show that no alternative can do the job so well.

Market theory suggests that the unrestricted right to trade, at prices agreed between trading partners and accompanied by a free flow of information about the resources being traded, outperforms other allocation methods in terms maximising the quantity and choice of articles available and getting them to the people who value them most. These collectively beneficial results are shown as arising from individuals’ pursuit of their own self-interest, and so being achievable without any intervention to regulate or modify individual behaviour. Although they operate at the level of the microeconomy (deploying resources efficiently in the most socially valued tasks), markets are therefore also argued to lead to desirable outcomes for the macroeconomy in terms of output growth, full employment, productivity growth (hence rising incomes) and technical progress which, as well as promoting efficiency, introduces new products, which widens the range of markets on offer to accommodate unmet needs.

Many advocates go on to identify unrestricted (‘free’) markets as a necessary (if not sufficient) condition for social freedom and democratic politics. Leaving individual choices to determine the allocation of human effort and its products not only makes them richer, more leisured and more educated—all extensions of choice and useful preparations for political participation—but also establishes a ‘consumer sovereignty’ under which governments and bureaucracies, as well as businesses, are constrained by their own self-interest to serve the public good. Other methods of allocation are, in this conventional economic analysis, not only less able to maximise the quantity and efficiency of a society’s resources, but also less compatible with unrestricted choice in other areas of life, and more vulnerable to the imposition of choice by strong governments and special interests. Non-market methods of transaction are, in comparison, held either to sacrifice individual interests to the collective good (failing to maximise either), or to benefit some at the expense of others, with a loss of efficiency (and justice) for the system overall.

1.1.1 The market: a definition

A market exists where many differentiated, uncoordinated agents engage in voluntary exchange of a reproducible product or productive service at openly advertised prices. Prices adjust through time to keep the product’s demand and supply in balance. At any one time, in any one place, the same price is available to all agents trading a homogeneous product.

An agent is an individual or cohesive group which takes and implements decisions to buy or sell, these being the two sides of any exchange.

Differentiation, of what agents currently have and of what they currently want, creates the conditions for mutually beneficial exchange between them. Agents will exchange units of one product for units of another if they believe this will come closer to satisfying their wants. The existence of many buying and selling agents ensures that each has a wide choice of agents with which to exchange. The differentiation among buyers and sellers, and their number, ensures that transactions are uncoordinated. Exchange can then take place without any elements of monopoly (co-ordinated selling) or monopsony (co-ordinated buying).

By product is meant any raw material, manufactured good or consumable service which one agent can supply in return for specified products from another agent. It is here defined to include two sub-categories often used as synonyms: good (a manufactured product) and commodity (a raw material which has undergone little or no processing).

Productive services arise from a special type of product which enters into the process of creating other products, but is not itself contained in them. The two most usually examined in economics are labour (the working-hours produced by employees who trade in the labour market) and capital (which trades in the financial markets as loans and share subscriptions, or in the capital-goods market as plant and machinery). Following convention, these will subsequently be referred to as ‘factors’, and the services they perform as ‘factor services’.

The term resources will be used to denote all products and factor services—all items which, because they have value to someone, command a positive price on the open market. Resources whose value arises from a stream of future income or utility, rather than a one-off burst of either, will also be referred to as assets in what follows.

A product is reproducible when its production process can continue indefinitely without permanently exhausting any of the resources that go into making it, and hence without its price trending inexorably upwards as supply is irreversibly run down. This makes production and transaction into endlessly repeatable ‘flow’ processes. A product’s supply may run out between one production run and the next but always being replenishable if demand still exists. Transactors need this assurance in order to form stable expectations of future prices, and avoid destabilising price movements due to panic buying or speculation.

Units of a product or productive service are homogeneous when they are sufficiently similar to be treated as interchangeable with other units of the product. Homogeneity ensures that buyers and sellers can decide whether (and how much) to exchange solely on the basis of the price being offered. Resources which are not fully interchangeable will trade in different markets at different market-clearing prices.

Exchange involves the voluntary transfer of resources from one agent to another, in return for other resources or for the legal entitlement to them. (In what follows, the terms exchange, transaction and trade will be used interchangeably.) Legal entitlement can include money, a product with little or no intrinsic value which is recognised as a medium of exchange, allowing flows of one product in exchange for another to be displaced in time or space. The special properties of money, which has replaced direct exchange (barter) in almost all market-based societies, are considered further in section 1.5. In general, the sale of a good involves its permanent physical transfer from buyer to seller, while the sale of a service (including productive services) involves the temporary transfer from buyer to seller of the product or factor that provides the service, for a specified time or until a specified amount of the service has been received. All forms of exchange entail the permanent or temporary transfer of mutually recognised property rights, which are defined and examined in more detail in section 1.4.

Price denotes the rate at which one product or productive service is exchanged for another. It is expressed as a sum of money or, where barter still occurs, as a ratio of physical amounts of the resources being exchanged. An agent’s demand is the amount of any product or productive service they wish to buy at a particular price, and supply is the amount they wish to sell at a particular price. These individual schedules come together to determine the market demand and supply, which set the equilibrium (market-clearing) price at which agents actually trade.

1.2 The market: a representation

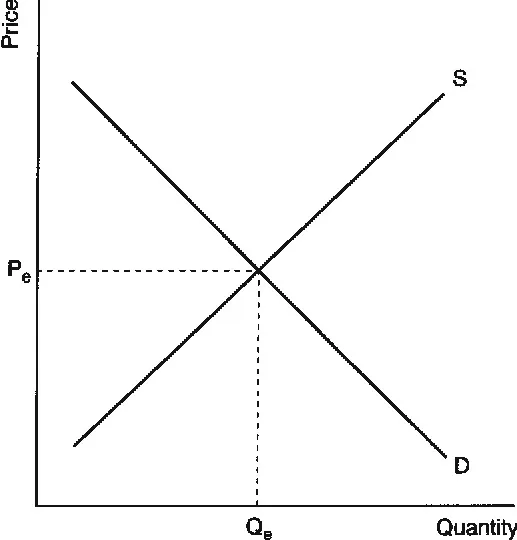

The concept of demand and supply gives rise to possibly the most familiar picture in economics, reproduced with some embarrassment as Figure 1.1. Market demand for a resource is shown as a declining function of its price, and market supply as an increasing function of its price. Both functions apply within a market period, the time it takes for all resources brought to the market to be exchanged and consumed, and for the supply of products—and the consumer wants that they sat-isfy—to be regenerated by another production run.

Figure 1.1 Demand and supply for a typical market

1.2.1 The demand curve

Market demand is shown as declining as the price increases. Since price has been placed on the vertical axis, it would conventionally be interpreted as a function of quantity, the price that agents are willing to pay to the quantity of the product they already have. By the principle of diminishing marginal returns, agents value each extra unit slightly lower than the previous one. The price they are willing to pay—the opportunity cost of other resources they will have to give up— therefore declines as purchased quantity rises.

The market demand function is also commonly interpreted as relating the quantity that buyers wish to purchase to the price they are asked to pay. As each agent has only limited funds (or resources that can be sold to raise funds), a rise in price reduces the total amount they can buy. It also induces them to switch, where possible, all or part of their previous expenditure to a substitute product which has now become relatively cheaper. (The substitute product is traded on another market, and its price is assumed to remain unchanged.) Market demand, the total of agents’ demands at each price posted, carries over (and probably accentuates) the downward slope of the individual demand functions.

In practice, therefore, the demand function can be taken as representing either quantity as a function of price or price as a function of quantity. Economists maintain a tactical ambivalence over which is the dependent and which the independent variable. Although price is placed on the vertical axis when demand is represented diagrammatically (as in Figure 1.1), quantity is made a function of price when demand is expressed as an equation.

1.2.2 The supply curve

Similarly, there are two ways of reasoning why the supply function shows a positive relation between price charged and quantity supplied. A higher price induces each selling agent to offer more, and more agents to join in as sellers, because they now expect the sale proceeds to be sufficient to buy something else that is worth more to them. And to obtain a larger quantity, buying agents must be willing to offer a higher price at the margin, because for selling agents the principle of diminishing marginal utility works in reverse. The more of the resource that is parted with, the more valuable the remainder becomes.

If the selling agent is also responsible for producing the resource, a further reason for rising supply price arises from their need, in turn, to buy more inputs and factor services. Increased quantity requires more labour, which will make itself available only if paid a higher wage. By the principle of diminishing marginal returns to fixed factors of production, another worker will not match the productivity of those already in place until more capital has been installed for them to work with, which cannot usually be done within the market period. If there is full employment, new workers must be offered more than the current wage to induce them to move from other employers. And if it is not possible to recruit more labour in the market period either, existing workers must be paid more to induce them to do the extra work themselves.

1.2.3 Equilibrium price

The equilibrium price for this market is Pe, where demand and supply functions intersect. This is the price all buyers can expect to pay for the product, and all sellers can expect to receive. If a buyer offers, or a seller demands, any other price, ‘market forces’ will push them back towards transacting at Pe. With too high an initial price, the excess of supply over demand forces sellers to clear their stock by cutting prices. With too low an initial price, the excess of demand over supply pulls price upwards, as buyers try to outbid one another for the remaining stock. Only at Pe can the market ‘clear’ within the market period.

The whole marketable stock of the product is assumed to change hands during this period, either because it is perishable so that suppliers must sell it to recover any value, or because buyers cannot delay receiving it without relinquishing some of that value. If the product is non-perishable, sellers are free to withhold part of their stock if they believe stronger demand or thinner supply will lead to a higher equilibrium price in subsequent periods. If the product is not essential to survival, buyers are free to delay their purchase if they believe greater supply or weaker demand will lead to a lower equilibrium price. However, although these speculative shifts in the supply and demand schedules will tend to be self-fulfilling— an outward shift in the supply curve reducing equilibrium price and an outward shift in the demand curve raising it—such movements will be stabilised by profit-seeking ‘speculators’ who, anticipating future price movements, will buy up non-perishable products whose equilibrium price is depressed by temporary oversupply or withheld demand, so as to re-sell at a higher price when this lapse below equilibrium causes demand to be stepped up or supply withheld. Under this stabilising characterisation, professional speculation concentrates trade temporally within the market period, since buyers and sellers cannot expect any windfall gains from delaying their transaction into future periods.

Just as speculation stabilises prices of non-perishable products across time by keeping supply and demand curves close to their fundamental levels (shown in Figure 1.1), ‘arbitrage’ equalises prices across space. If the same product trades at several different physical locations, professional ‘arbitrageurs’ will respond to any divergence in equilibrium prices among th...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: The Market Revolution

- 1. What Markets Are

- 2. Markets As Efficient Allocators

- 3. Markets As the Route to Full Employment

- 4. Markets As Engines of Growth

- 5. Markets As Information Processors

- 6. The Negotiated Alternative: Relational Transaction

- 7. Mediated Alternatives: Administered and Informed Transaction

- 8. The Firm: Redesigning the Market

- 9. The International Market

- 10. Market Rewards: The Distribution of Income

- 11. Disinventing Government: The State Goes On Sale

- 12. Conclusion: Its Limits

- References