- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Architect's Guide to Feng Shui

About this book

Cate Bramble has devoted her career to highlighting the differences between 'feng shui-lite' as a fashionable pursuit in contrast to the original intentions of the Chinese masters. Here she presents the authentic principles in a technical, no-nonsense pocket book specifically for architects.

As clients become more demanding and the competition for projects heats up, the architect is well advised to have many strings to their bow. This practical guide includes line illustrations that present the principles of feng shui, the Chinese art or practice in which a structure or site is chosen or configured so as to harmonize with the spiritual forces that inhabit it, and their application in architecture through planning principles, services, building elements and materials, in an accessible, easy reference format. The feng shui-savvy architect can also benefit from feng shui's ability to match structures and land, and the peculiar capacity of authentic feng shui to forecast development-related concerns including cost overruns, quality issues - even worker injuries and trade disputes!

The author explains feng shui from archaeological sources and evidence of practice in the east, contrasting it with what passes for feng shui in the west. She analyses the practice in terms of such concepts as western systems theory, viewshed, space syntax and the 'pattern landscape' theory of urban planning. For the first time, the Sustainable implications of feng shui design are explained with reference to the latest developments in behavioural and cognitve sciences, evolutionary biology and other western viewpoints.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture GeneralChapter 1

Introduction: global perspective

Macrocosm to microcosm

The jewel that we find, we stop and take it

Because we see it; but what we do not see

We tread upon.

Because we see it; but what we do not see

We tread upon.

Christopher Alexander in A Pattern Language (1977) and The Timeless Way of Building (1979) says there is only one way to create human structures that express our humanity and aliveness. Perhaps that explains why Benoit Mandelbrot saw fractal structures only in classic architecture.1 There must be something to an ancient building if it has managed to sustain us for thousands of years and still compels innovative thinkers to return to its fertile roots.

We want to believe that cities developed almost accidentally, according to political and commercial interests. We acquire that idea from our culture, which understands life as linear history against the traditional view of life as cyclical myth.2 Yet, cities as we understand them are a very recent phenomenon for human communities. The current idea developed from something the Greeks called the polis (which functioned like an extended family) but did not form what we would identify as a ‘city’ before the European Middle Ages. Before then, and all around the world until quite recently, cities were an expression of the sacred.

Figure 1.1

Viewed from above, Gaudì’s Casa Milo looks as organic and timeless as any natural setting. From a model in DesignWorkshop Lite.

Figure 1.2

The Dome of the Rock provides the squared circle of a traditional building. From a model in DesignWorkshop Lite.

James and Thorpe (1999), in Ancient Mysteries, wonder why our ancestors shared the urge to reshape the planet for reasons that do not look quite sane to us. Mound building, straight and wide paths that run for kilometers to nowhere, stone monuments that chart the movements of celestial objects, cities that align to the cardinal directions and whose buildings can be used as astronomical instruments are part of our human heritage. Wheatley (1971), in The Pivot of the Four Quarters, showed that urban design expressed in a variety of Asian literature and architecture, and in some nineteenth-century American towns, conveyed the same designs. What were our ancestors thinking?

Human urban design in many places and times has conformed to the same mythic vision because it most profoundly expresses what makes us human. The planning of human habitations has generally been meant for a larger spiritual purpose—and generally an unconscious one.3 Traditional habitation seeks to mirror nature's ways as a form of respect, and human cultures provide mythic justification for these acts. Buildings everywhere used to be imbued with magic, carefull oriented to the heavens and nearby spiritual features of the land, and integrated with the world at large.

Planetary rotation helped us define cardinal directions which, along with the centre, ‘here’, assumed importance for humans more than 10000 years ago. Cardinal and intercardinal directions impose cultural structure on nature and serve as a memory aid that strengthens and transmits modes of thought over generations. Humans first mapped the heavens, identified the celestial landscape with land formations, and arranged their dwellings and cities according to the scheme. Settlements were built to invoke these features. Designing on this scheme revealed the underlying movements of the universe.

Myth provides the ultimate technology because it uses our brain and its capacity for memes and memeplexes to encode extremely sophisticated information and transmit it far beyond our own time. A culture's myths make it possible for its members to acknowledge reality (nature). Myth served as the original way to encode traditional knowledge, including the science of a culture.

Petroglyphs at Teotihuacán orient the city on an east–west axis with respect to the sky and can be used for astronomy (one pair of markers indicates the Tropic of Cancer). The Talmud says that if a town is to be laid out in a square (which identifies what is made by humans), its sides must correspond to the cardinal directions and align with Ursa Major and Scorpio (Eruvim 56a). The practices of al-qibla, built into the Ka'aba and all mosques, orient east and west sides to sunrise at the summer solstice and sunset at the winter solstice. The south faces of mosques and the Ka'aba align to the rising of Suhail (Canopus). Spatial configurations like these form part of many cultures’ scientific systems, but Westerners often cannot breach their cultural framework and accept this understanding of the world.4

Jauch (1973) in Are Quanta Real? considered that cyclical movement, a common feature in traditional and mythic thought, helps humans understand the enormity of the universe—including their own insignificance—as well as reality. (Cyclical thought, in Jauch'sopinion, is eminently useful today as a heuristic technique simply because it works so well.) Traditional building provides a way for humans to be constantly reminded of their insignificance, just as myths typically celebrate the deeds of those who humble themselves. The mythic model articulates a respectful interaction with nature to draw upon its inspiration and power.

Figure 1.3

The Globe Theatre of Elizabethan England features classic shapes aligned for good viewing, and acoustics. Moreover, the bulk of the building lies at the back. From a model in DesignWorkshop Lite.

Cosmology and the city

The city of Shang was carefully laid out, it is the centre of the

four quarters; majestic is its fame, bright is its divine power; in

longevity and peace it protects us, the descendants.

Our architecture and other cultural artefacts unconsciously reflect ideas of cosmic order and embody our values and social reality. They also have the potential to inspire our species’ more troublesome instincts to conform to specific customs. Studies indicate that our instinctive urges can be guided merely by the presence and arrangement of nonhuman beings, landscape, and architecture.To the ancients, subtly persuading humans to be their best meant creating habitations in harmony with nature. The ancients assessed all probable consequences of erecting a structure on the balance of nature and designed for the relationship between a building and the cosmos. Out of Greek geometry a few centuries ago Western culture fashioned the concept of ‘ sacred geometry’ to supply a spiritual plan for monumental architecture.5 However, thousands of years earlier Chinese culture devised its own system—a radically different approach to addressing the same issues.

Careful planning in traditional building was essential—especially with capital cities, which assumed the responsibility for the welfare of a state. What you see in the planning of a traditional city—and especially in the planning of premodern Chinese cities—flows from what Mircea Eliade identified as the sacred practice of building.6

Reality is a function by which humans imitate the celestial archetype

Trinh Xuan Thuan in Chaos and Harmony (2001) sees the universe applying certain laws to create diversity. Harmony supplies the pattern and chaos supplies creative freedom. All the high cultures of Asia and most of the high cultures of the premodern world built their cities as a terrestrial celebration of the universe.

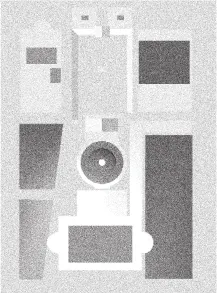

Figure 1.4

A large complex like Knossos follows the classic shapes, but it also brilliantly conveys the genius of the society that constructed it. From a model in DesignWorkshop Lite.

Figure 1.5

The Pantheon complex is aligned symmetrically but follows the patterns humans expect. From a model in DesignWorkshop Lite.

The traditional worldview of Chinese culture supplies a profound cosmology for generating symbolism. A Chinese city was built only after a considerable list of requirements was satisfied. Local influences (xingqi), dynamic powers of what an ancient Roman might call the genius loci or ‘spirit’ of a place, were determined before construction in accordance with the shape of local terrain and the stars and planets wheeling overhead. No expense was spared to ensure that the city conformed to traditional design principles. Space–time is paramount in the traditional ideology of Chinese building, which resides in the ‘Kaogong ji’ (Manual of Crafts) section of the Zhou li. The site and date for groundbreaking had to be confirmed by heaven in advance. In the Book of Odes one Neolithic ruler consults tortoise shells to obtain information whether a particular area offers the appropriate place and time for construction.

Humans mimic the macrocosm and the microcosm by conducting themselves so that they main...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Chapter 1 Introduction: global perspective

- Chapter 2 Expert rules

- Chapter 3 Protoscientific and pseudoscientific conventions

- Chapter 4 Calculations

- Chapter 5 Planning

- Chapter 6 Environmental assessment

- Chapter 7 Human factors

- Chapter 8 Crime and its relation to the environment

- Chapter 9 Structures

- Chapter 10 An overview of the theory of time and space

- Chapter 11 Form and shape theory in time and space theory

- Chapter 12 Services

- Chapter 13 Overlooked and overblown issues of drainage, water supply and storage, ventilation, electrical supply and installation, lighting, and soundChapter Overlooked and overblown issues of drainage, water supply and storage, ventilation, electrical supply and installation, lighting, and sound

- Chapter 14 Building elements

- Chapter 15 Resources

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Architect's Guide to Feng Shui by Cate Bramble in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.