eBook - ePub

Nero

About this book

The reign of Nero is often judged to be the embodiment of the extravagance and the corruption that have, for many, come to symbolise ancient Rome. David Shotter provides a reassessment of this view in this accessible introduction to Nero, emperor of Rome from 54 to 68 AD. All the major issues are discussed including:

• Nero's early life and accession to power

• Nero's perception of himself

• Nero's domestic and international policies

• the reasons for Nero's fall from power and its aftermath.

This new edition has been revised throughout to take account of recent research in the field.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

FAMILY AND POLITICS

The emperor, Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, was the last ruler of the Julio-Claudian dynasty (31 BC–AD 68). His death, precipitated by military rebellion in the western half of the empire, was viewed with great relief by many members of the senatorial order; it demonstrated too that the ‘secret of empire was out, that an emperor could be made elsewhere than at Rome’ (Tacitus Histories I.4) and it prompted some at least to consider alternatives to the concept of dynastic succession (see Appendix II); Nero, by his behaviour, was seen as hastening the end of the dynasty, but he was viewed more as a product than as the cause of a flawed system.

Dynasticism in Roman politics went back beyond the principate of Augustus; it had been amply demonstrated in the factional manoeuvrings that had characterized the politics of the late republic as groups of nobles joined together to climb the senatorial career ladder (cursus honorum) and thereby win honour and glory for themselves and their families. Gradually, however, such ambitions came to appear too self-indulgent, particularly when the factions began to harness elements of the Roman army in their support. This was the route to chaos and civil war, and by the first century BC it was becoming clear to many that the republic needed the guidance of a central ruler; the real debate surrounded the nature, status and ‘conditions of service’ of such a person. The crudeness, for example, of the methods of Julius Caesar alienated many amongst the senatorial order; to them, he became a ‘king’ (rex), that most hated figure of Rome’s past. Yet many ordinary people valued the strength and apparent security of his patronage; to them, the arrival on the scene of a new Caesar (Octavian – the future emperor, Augustus) was a guarantee of the continuity of what they had come to value in the dictatorship of Caesar (49–44 BC). The blatant illegality of Octavian’s rise to power was, to many, a small price to pay for this.

Octavian’s eventual primacy was guaranteed by his and Agrippa’s defeat of Antonius and Cleopatra at the battle of Actium in 31 BC; a war-weary world was not looking for further conflict – rather the return of stability, a restored republic. Augustus Caesar set about this restoration partly by institutional change and adaptation, and partly by the patronage which his prestige (auctoritas) and the wealth of the newly conquered Egypt enabled him to organize. However, in one significant respect there was little real change: the late republic had had only a tenuous institutional control of its army, and it was this that had enabled its incumbent commanders to use the army to further their own ambitions. Although by various reforms Augustus brought to the army a greater measure of stability, he did little to solve the central dilemma; the army under the early principate belonged to the respublica only in so far as the emperor was the embodiment of the respublica. Thus, while under a strong princeps there might appear to be no problem, a weak or uninterested princeps, such as Nero seemed to be, demonstrated that control of the army and the hazards which accompanied this were every bit as dangerous to the fabric of the state as during the ‘old republic’.

Augustus’ personal success depended upon his prestige, his patronage and control, his personality, and his success in tackling some of the problems by which people had been troubled. However just as crucial to his success were the facts that he devised a system of control that suited him and his times, and that he achieved this gradually; it is little wonder that the historian Tacitus reflects upon the apparently surreptitious nature of the growth of Augustus’ dominance.

However, Augustus’ and the republic’s real difficulty lay in planning for a future in the longer term, and in devising a scheme which would preclude a return to the extravagances of factional strife which had formerly caused so much trouble. Augustus’ preferred solution lay in the construction of a scheme of dynastic succession. The chief difficulty inherent in this or any other scheme was, as Tacitus shows, that the Augustan principate was widely seen as just that, and that people associated peace and stability with Augustus alone; for many, he had after forty-four years assumed a kind of immortality which his ever-youthful appearance on the coinage seemed to confirm.

Augustus had emerged from the battle of Actium as a magistrate with a special mandate; whether this position was to be transmitted, and if so, to whom, were problems to be resolved. It is evident, however, that not everybody believed that Augustus’ ‘special role’ should be extended to someone else after his death; Tacitus reports that, as Augustus’ end approached, a few talked of the blessings of libertas (‘freedom from dominance’), while in the reign of Tiberius (AD 14–37) a historian named Cremutius Cordus was put to death on the grounds that in his Annals he had praised Marcus Brutus and dubbed Gaius Cassius ‘the last of the Romans’ (Tacitus Annals 1.4, 2; IV.34, 1). Later, in the midst of the civil war which followed Nero’s death, his successor, Servius Galba, eloquently put the case for the rejection of a dynastic succession policy in favour of the choice of the best man available (Tacitus Histories 1.15–16; see Appendix II).

It may be assumed that Augustus’ view about the succession had its roots in his own past: although Tacitus specifies an occasion when Augustus discussed the possibility of his powers passing to a man outside his own family, it is clear that his general determination was that he should be succeeded by a member of his own family – the Julii, extended by his marriage to Livia into the Claudii.

Augustus’ extended family had an abundance of potential heirs, but death and suspected intrigue dealt severe blows to his plans for them. Marcellus (his nephew) died in 22 BC, while his stepson, Nero Claudius Drusus, died in 9 BC from complications following a fall. Augustus’ adopted sons, Gaius and Lucius Caesar, succumbed respectively in AD 4 and 2; in AD 7 Agrippa Postumus was exiled for an offence, the nature of which it is now hard to unravel. In the meantime, in 6 BC, frustration at the state of his life drove Tiberius (Augustus’ other stepson) into retirement on the island of Rhodes; four years later, Tiberius’ wife and Augustus’ daughter Julia was exiled following the discovery by her father of a host of adulterous relationships with men with very prominent names, including Iullus Antonius, Appius Claudius Pulcher and Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus.

It appeared by AD 4 that a succession policy based upon Augustus’ family was near to collapse; in that year the princeps adopted Tiberius and Agrippa Postumus jointly as his sons, and required Tiberius to adopt his nephew, Germanicus. Augustus had compromised; while it might no longer be possible for him to be succeeded by a member of the Julian family, he could ensure that his faction would re-emerge in the next generation. The strife between Julians and Claudians appears murderous, but ironically it provided an important ingredient to the success of the Augustan principate for, with two factions – Julians and Claudians – firmly anchored within the system, there was a place in the principate for the factional rivalry which had been an inherent feature of the old republic. Augustus and his Julian family, with its promotion of new families, were the heirs of the populares of the republic, while Livia’s connections and the sternly traditional outlook of her son Tiberius made him and the Claudian family a natural rallying point for the descendants of the old optimates. In this way, it was guaranteed that factional feuding amongst the nobility became part of the principate, rather than continuing on the margins as a danger to the new system.

Tiberius succeeded Augustus in AD 14, and thus Augustus’ special mandate had been transmitted to a new generation. The act of transmission, however, conveyed the principate on to new ground; all the powers and honours that Augustus had enjoyed were, despite Tiberius’ protests, conveyed to him en bloc; he had not, of course, won them, and his title to them came purely by way of the auctoritas of Augustus.

Tiberius’ sensitivity over this is demonstrated by Tacitus (Annals I.7, 10) when he writes of the anxiety of the new princeps to counter the gossip that he owed his position to Livia’s ambitions and her influence over her senile husband.

The respublica had become a hereditary monarchy, and in the words of Galba in AD 69, Rome had become the ‘heirloom of a single family’. Galba’s solution to this situation lay in what Tacitus (Life of Agricola 3) referred to as the reconciliation of principate and liberty. As demonstrated in the political fictions of the late first and early second centuries AD this meant that the incumbent princeps chose as his adopted son and successor the man who by the consensus of his peers in the senate appeared to be the best available. In this way, it seemed, the post of princeps effectively became the summit of the senatorial career ladder, and every senator could – in theory at least – aspire to it. As we have seen, there is evidence that at one time Augustus had given thought to this, as Tacitus mentions the names of four such senators who were considered by Augustus as possible successors.

It was believed by some that Augustus would have preferred in AD 14 to have been able to elevate Germanicus Caesar (the son of Nero Drusus) who had married his granddaughter Agrippina. In any event he clearly intended that Germanicus should succeed Tiberius, and required his adoption by Tiberius despite the fact that Tiberius had a son of his own – Drusus – from his first marriage to Vipsania, the daughter of Marcus Agrippa. The evidence suggests that Tiberius intended to honour this requirement, but the plan was dashed by Germanicus’ premature death in AD 19.

Germanicus and Agrippina had had three sons – Nero, Drusus and Gaius (Caligula) – and three daughters – Agrippina, Livilla and Drusilla. The elder Agrippina and her older sons (Nero and Drusus) were removed as a result of the intrigues of Lucius Aelius Sejanus, the prefect of the Praetorian Guard, who was himself put to death in AD 31, apparently for plotting the death of the surviving son, Caligula. Of the daughters, Tiberius arranged the marriage of Agrippina to Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, consul in AD 32, a man with a good republican pedigree and a poor reputation; these were the parents of the future emperor Nero.

Although Tiberius did not formally adopt a successor, the inevitable choice lay between his natural and adopted grandsons – Tiberius Gemellus and Gaius Caligula. In March of AD 37, Caligula succeeded Tiberius, and within a year Gemellus was dead, possibly as a figurehead of a plot of ‘Claudian’ senators to remove Caligula. Caligula’s interpretation of the principate marked a sharp contrast to those of Augustus and Tiberius; perhaps inheriting character traits of both his mother and his father, Caligula, instead of seeing himself as bound into the senatorial governing machine, actively promoted a personality cult, built around himself, together with living and dead members of his family. All of them were commemorated on Caligula’s coinage; his sisters, indeed, were portrayed in quasidivine form as ‘The Three Graces’. It is likely that this alienated many, and perhaps added force to the circulating stories which suggested that the emperor encouraged worship of himself as a living deity. It is hard to say how far this was true, but the totality of the evidence suggests a monarch whose ideas were absolutist, and who perhaps saw the Hellenistic kings of Asia Minor as his nearest role models.

At first Caligula placed his succession hopes upon his sisters and their husbands, but he soon became disillusioned with them. When he was assassinated in January of AD 41 he left no named heir, and among some of those involved in the plot to kill him there was probably a leaning to a proper return to the republic in preference to a continuation of the principate. However, the Praetorian Guard played its hand, and ‘nominated’ one of the last surviving members of the Julian and Claudian families, Germanicus’ younger brother, Claudius. It remains uncertain whether the ‘choice’ of the Guard was as fortuitous as is suggested by the classical sources. It is possible that Claudius was at least a figurehead in the plot to remove his nephew, and may even have been an active participant.

Although Suetonius records an occasion when Augustus appears to have appreciated that there was more to Claudius than met the eye, the imperial family in general appears to have found Claudius an embarrassment because of his physical infirmities and to have acted in a determined manner to keep him out of the limelight – until, that is, Caligula bestowed upon his reclusive uncle a suffect consulship in AD 37.

Until then his life had revolved around the study of history, from which his own principate was to show that he had gleaned important lessons – especially about the development and administration of Rome’s empire. At home, however, he did not emerge as the ‘republican’ figure that some, perhaps, had expected. In the event, though less capricious, he was as centralist as Caligula – and perhaps in a more thoroughgoing way. However, the positive aspects of Claudius’ thinking were for many – senators, in particular – overshadowed by the intrigues and scandals which peppered his reign, most of which arose out of the emperor’s apparent inability to stamp his authority on those in his immediate ‘court circle’.

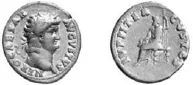

Plate 1 Aureus of Nero (AD 65), showing the seated figure of ‘Jupiter the Guardian’ (IVPPITER CVSTOS). The coin may have been issued to commemorate Nero’s escape from Piso’s conspiracy.

The emperor’s third wife, Valeria Messalina, who bore him two children, Britannicus and Octavia, was put to death in AD 48 following her bigamous marriage to a young senator, named Gaius Silius. It may not have been an accident that Silius’ father and mother had been close associates of Germanicus and the elder Agrippina, particularly in view of the fact that Messalina’s fall opened the way for the younger Agrippina to become Claudius’ fourth wife; this marriage took place early in AD 49, and the rise of Agrippina’s son now began to achieve real momentum.

2

NERO’S EARLY LIFE AND ACCESSION

Julia Agrippina was the fourth of the surviving children of Germanicus Caesar and the elder Agrippina, and the eldest of their three daughters; Germanicus’ marriage to Agrippina and Augustus’ insistence in AD 4 that he be adopted by Tiberius ensured that in the popular mind this family was viewed as representing the true line of descent from Augustus. The younger Agrippina was born on 6 November AD 15, while her parents were on the Rhine, where her father commanded the eight legions of the two Germanies. Tradition has put her birthplace at Ara Ubiorum (Cologne), which was later, in AD 50, promoted to the status of colonia, and renamed Colonia Claudia Ara Augusta Agrippinensium. Thus the former tribe of the Ubii were henceforth to be known as the Agrippinenses.

As we have seen, the family’s fortunes during Tiberius’ reign seemed to plumb ever-greater depths, with the death of Germanicus in AD 19 and the attack which was launched in the 20s by Sejanus on the elder Agrippina and her sons. This culminated in their deaths in prison – Nero (the oldest son) in AD 30 and the elder Agrippina and her second son, Drusus, in AD 33. In the meantime the younger Agrippina was in AD 28 married to Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus (who became consul in AD 32), while in AD 31 Caligula and his two other sisters were taken to reside with Tiberius in his isolated retirement on the island of Capreae. Caligula survived to become princeps upon Tiberius’ death in AD 37; his youngest sisters were in AD 33 given good marriages – Drusilla to Lucius Cassius Longinus, and Julia Livilla to Marcus Vinicius; these men had shared the consulship of AD 30.

The sisters and their husbands were to play prominent parts in the brief principate of Caligula (AD 37–41). His favourite sister was Drusilla; Gaius had annulled her marriage to Cassius Longinus and married her instead to Marcus Lepidus, a man closer in age to herself. It was upon her that e...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Family and politics

- 2 Nero’s early life and accession

- 3 The new Augustus

- 4 Empire and provinces

- 5 Hellenistic monarch or Roman megalomaniac?

- 6 Opposition and rebellion

- 7 The end of Nero: civil war

- Conclusion

- Appendix I: Principal Dates in Nero’s Life and Reign

- Appendix II: Galba’s Speech to Piso

- Appendix III: Nero’s Golden House

- Appendix IV: Glossary of Latin Terms

- Appendix V: Accounts of Nero’s Life and Principate

- Select Bibliography

- Index of Persons and Places

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Nero by David Shotter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.