![]()

Part 1

Audio Basics

![]()

| 1 | The Evolution of Audio Post Production |

| Hilary Wyatt |

An Overview

The term audio post production refers to that part of the production process which deals with the tracklaying, mixing and mastering of a soundtrack. Whilst the complexity of the finished soundtrack will vary, depending on the type of production, the aims of the audio post production process are:

- To enhance the storyline or narrative flow by establishing mood, time, location or period through the use of dialogue, music and sound effects.

- To add pace, excitement and impact using the full dynamic range available within the viewing medium.

- To complete the illusion of reality and perspective through the use of sound effects and the recreation of natural acoustics in the mix, using equalization and artificial reverbs.

- To complete the illusion of unreality and fantasy through the use of sound design and effects processing.

- To complete the illusion of continuity through scenes which have been shot discontinuously.

- To create an illusion of spatial depth and width by placing sound elements across the stereo/ surround sound field.

- To fix any problems with the location sound by editing, or replacing dialogue in post production, and by using processors in the mix to maximize clarity and reduce unwanted noise.

- To deliver the final soundtrack made to the appropriate broadcast/film specifications and mastered onto the correct format.

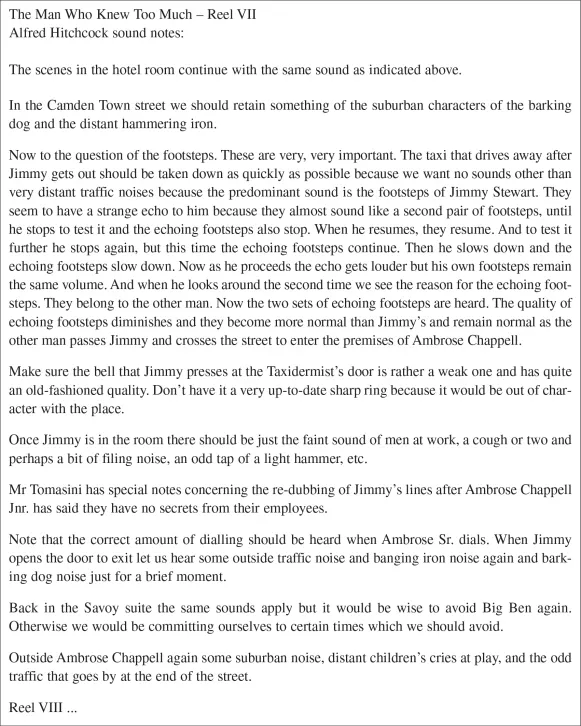

Figure 1.1 Alfred Hitchcock’s sound spotting notes for The Man Who Knew Too Much (courtesy of The Alfred Hitchcock Trust).

A Little History: the Development of Technology and Techniques

Despite the fact that audio post production is now almost entirely digital, some of the techniques, and many of the terms we still use, are derived from the earliest days of film and television production.

The First Sound Film

The first sound film was made in America in 1927. The Jazz Singer was projected using gramophone records that were played in synchronization with the picture: this was referred to as the release print. Film sound played on the current enthusiasm for radio, and it revived general public interest in the cinema. Around the same time, Movietone News began recording sound and filming pictures of actual news stories as they took place, coining the term actuality sound and picture. The sound was recorded photographically down the edge of the original camera film, and the resulting optical soundtrack was projected as part of the picture print.

At first, each news item was introduced with silent titles, but it was soon realized that the addition of a commentary could enliven each reel or roll of film. A technique was developed whereby a spoken voice-over could be mixed with the original actuality sound. This mix was copied or recorded to a new soundtrack: this technique was called ‘doubling’, which later became known as dubbing. Any extra sounds required were recorded to a separate film track, which was held in sync with the original track using the film sprockets.

Early Editing Systems

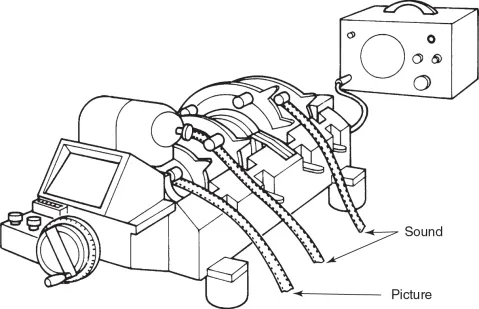

Systems were developed that could run several audio tracks in sync with the picture using sprocket wheels locked onto a drive shaft (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 A film synchronizer used for laying tracks (courtesy of A. Nesbitt).

The synchronizer and Moviola editing machines were developed in the 1930s, followed by the Steenbeck. The fact that shots could be inserted at any point in a film assembly, and the overall sync adjusted to accommodate the new material, led to the term non-linear editing.

Dubbing/re-recording

Early mixing consoles could only handle a limited number of tracks at any one time – each channel strip controlled a single input. Consoles could not play in reverse, nor drop in to an existing mix, so complete reels had to be mixed on-the-fly without stopping. This meant that tracks had to be premixed, grouping together dialogue, music and fx tracks, and mixes took place in specially built dubbing theatres. Each of the separate soundtracks was played from a dubber, and it was not unusual for 10 machines to be run in sync with each other. A dubbing chart was produced to show the layout of each track.

Early dubbing suffered from a number of problems. Background noise increased considerably as each track was mixed down to another and then copied onto the final print – resulting in poor dynamic range.

The frequency range was also degraded by the dubbing process, which made each generation a poor copy of the first. To improve speech intelligibility, techniques were developed which involved modifying the frequency response of a signal. However, the lack of a uniform standard meant that many mixes were almost unintelligible in some poorly equipped theatres. To tackle the problem, The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences developed the ‘Academy Curve’ – an equalization standard which ensured that all engineers worked to the same parameters, and which standardized monitoring in dubbing theatres and cinemas. This standard was maintained until the 1970s, when film sound recording was re-appraised by the Dolby Corporation.

By the end of the 1930s, the film industry had refined all the fundamental techniques needed to produce a polished soundtrack – techniques that are still used to some extent today.

Post Sync Recording

It became standard practice to replace dialogue shot on set with better quality dialogue recorded in a studio. American producers needed a larger market than just the English speaking world, and so post synchronization techniques were developed to allow the re-voicing of a finished film in a foreign language. A picture and sound film loop was made up for each line. This loop could be played repeatedly, and the actor performed the line until an acceptable match was achieved. A chinagraph line marked on the film gave the actor an accurate cue for the start of each loop. This system of automatic dialogue replacement or looping is still in use today, although electronic beeps and streamers have replaced the chinagraph lines. Footsteps and moves were also recorded to picture, using a post sync technique invented by Jack Foley, a Hollywood sound engineer. This technique is still used on many productions and is known as foley recording.

Stereo

The first stereo films were recorded using true stereo to record dialogue on set. Unfortunately, once the footage was cut together, the stereo image of the dialogue would ‘move’ on every picture cut – perhaps even in mid-sentence, when the dialogue bridged a cut. This was distracting and led to the practice of recording dialogue in mono, adding stereo elements later in post production. This is still standard practice in both TV and film production.

In 1940, Walt Disney’s Fantasia was made using a six-channel format which spread the soundtrack to the left, right and centre of the screen, as well as to the house left, right and centre channels. This echoed the use of multichannel formats in use today, such as Dolby Surround, Dolby Digital and DTS.

The desire to mix in stereo meant an increase in the number of tracks a mixer had to control. Mixing was not automated until the late 1980s, and the dubbing mixer had to rely on manual dexterity and timing to recreate the mix ‘live’ on each pass. Early desks used rotary knobs, rather than faders, to control each channel. The introduction of linear faders in the 1960s meant that mixers could more easily span a number of tracks with both hands. Large feature-film mixes often took place with two or three mixers sat behind the console, controlling groups of faders simultaneously.

Magnetic Recording

Magnetic recording was developed in the 1940s and replaced optical recording with its much improved sound quality. Up to this point, sound editors had cut sound by locating modulations on the optical track, and found it difficult to adjust to the lack of a visual waveform. Recent developments in digital audio workstations have reversed the situation once more, as many use waveform editing to locate an exact cutting point. Magnetic film was used for film sound editing and mixing right up to the invention of the digital audio workstation in the 1980s.

The arrival of television in the 1950s meant that cinema began to lose its audience. Film producers responded by making films in widescreen, accompanied by multichannel magnetic soundtracks. However, the mag tracks tended to shed oxide, clogging the projector heads and muffling the sound. Cinema owners resorted to playing the mono optical track off the print (which was provided as a safety measure), leaving the surround speakers lying unused.

Television

Television began as a live medium, quite unlike film with its painstaking post production methods. Early television sound was of limited quality, and a programme, once transmitted, was lost forever. In 1956, the situation began to change with the introduction of the world’s first commercial videotape recorder (VTR). The Ampex VTR was originally designed to allow live television programmes to be recorded on America’s East Coast. The recording would then be time delayed for transmission to the West Coast some hours later. This development had two significant consequences. Firstly, recordings could be edited using the best takes, which meant that viewers no longer saw the mistakes made in live transmissions. Secondly, music and sound effects could be mixed into the original taped sound. Production values improved, and post production became an accepted part of the process.

In 1953 NTSC, the first ever colour broadcast system, was launched in the US based on a 525-line/60 Hz standard. The PAL system, based on a 625-line/50 Hz standard, was introduced across Europe (except for France) in the early 1960s. At the same time, SECAM was introduced in France. This is also a 625-line/50 Hz standard, but transmits the colour information differently to PAL.

Video Editing

This was originally done with a blade, and involved physically cutting the tape, but this was quickly superseded by linear editing. Here, each shot in the edit was copied from a source VTR to the record VTR in a linear progression. Tape editing is still used in some limited applications, but the method is basically unchanged. However, just as early film soundtracks suffered from generational loss, so did videotape because of the copying process. This problem was only resolved with the comparatively recent introduction of digital tape formats.

Timecode

Sound editing and sweetening for video productions was originally done using multitrack recorders. These machines could record a number of tracks and maintain sync by chasing to picture. This was achieved by the use of timecode – a technology first invented to track missiles. Developed for use with videotape in 1967, it identified each individual frame of video with accurate clock time, and was soon adopted as the industry standard by the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers (SMPTE). The eight-digit code, which is at the heart of modern editing systems, is still known as SMPTE timecode.

Videotape Formats

Early video equipment was extremely unwieldy, and the tape itself was 2 inches wide. In the 1970s, 1-inch tape became the standard for studio recording and mastering. Because neither format was at all portable, location footage for television (e.g. news and inserts for studio dramas, soaps and sitcoms) was shot using 16-mm film. This remained the case until the U-matic ¾-inch format was released in 1970. Designed to be (relatively) portable, it marked the beginnings of electronic news gathering or ENG. Both picture and sound could now be recorded simultaneously to tape. However, it was the release of Sony Betacam, and its successor Betacam SP in 1986, which spelled the end of the use of film in television production, although 16- and 35-mm film continued to be used for high-end drama and documentary. Betacam SP also replaced the use of 1-inch videotape and became the industry standard format until the 1990s.

Dolby Stereo

In 1975, Dolby Stereo was introduced to replace the then standard mono format. In this system, a four-track LCRS mix (Left, Centre, Right, Surround) is encoded through a matrix as two tracks carrying left and right channels, from which a centre track and surround track are derived. These two channels (known as the Lt Rt – Left total Right total) are printed optically on the film edge and decoded thr...