1

What is cognitive behavioural therapy?

There is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so.

Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act II, Scene 2

The description is not the described.

Krishnamurti (1996)

Chapter contents

- CBT is a structured, evidence-based treatment

- There are various schools of CBT but the treatment arising from Beck’s work is focused on here

- CBT understands problems by considering the interaction between environment, thoughts, feelings, physical sensations and behaviours

- There are three levels of thinking; negative automatic thoughts, rules for living and core beliefs. Treatment is focused on modifying these three levels of thinking and associated unhelpful behaviours with the aim of alleviating negative feelings and physical reactions associated with anxiety and depression

- The key elements of CBT include a collaborative understanding of how current problems are being maintained and the use of specific interventions both in and out of treatment sessions in order to tackle such problems

INTRODUCTION

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is a highly structured, evidence-based treatment that aims to address patients’ current problems. The treatment is goal oriented, in that goals are agreed between the patient and clinician usually in terms of improving the patient’s distressing emotional states and unhelpful patterns of thinking and behaviour. All of these may interfere with the patient’s day-to-day functioning. Each aspect of treatment is explicitly discussed and the patient and clinician work together to solve the patient’s problems using a range of interventions informed by a coherent cognitive behavioural treatment rationale and working within an agreed, short-term (average 12–18 sessions) timeframe. Central to the cognitive behavioural model is the idea of a normalizing treatment rationale. Thus, the emotional responses that characterize anxious and depressive states are seen to exist on a continuum with normal emotional reactions that we experience every day. Thus, when looking at the evidence base for CBT treatments there is a wealth of research data that demonstrate many of the cognitive and behavioural features of common mental health problems are also present in individuals who do not meet the diagnostic criteria for such problems. Examples include the frequency of reported intrusions (a feature of obsessive compulsive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder) in the general population; experiments in mood induction demonstrating a link between low mood and negative thoughts in both depressed and non-depressed subjects; the tendency for all humans when anxious to pay more attention to the object or event that is the focus of our fear, as demonstrated in threat cue detection experiments. For a comprehensive review of this literature the interested reader is directed to Williams et al. (1997). So what is the difference between a normal human response to distress and the nature of the response that is seen in mental health problems? The difference is that in mental health problems these emotional responses are seen as more intense, persistent and out of proportion with our usual responses.

It needs to be acknowledged that there are many different ‘schools’ of cognitive behavioural therapy. Gilbert (1996) identified at least 16 schools of CBT, each of which places different emphases on behavioural and/or cognitive elements and/or interpersonal factors within CBT theory and practice. For example, if the reader compares the work of Marks (Marks et al., 1983) with that of Barlow (Barlow et al., 1989) and Clark (Clark et al., 1999) in the treatment of panic and agoraphobia as an example, the treatment methods, while sharing some commonalities, also contain some divergent theoretical principles and interventions. In addition, some CBT models are more evidence based than others and it is a mistake to assume that the acronym CBT is synonymous with the idea of its treatments being evidence based. For example, a series of randomized controlled trials in the area of depression validated the original work of Beck and colleagues (Beck, 1976; Beck et al., 1979) but there is some debate over the conclusions drawn regarding the efficacy of the original CBT for depression studies (see Williams, 1997, for a meaningful discussion of these issues). Meanwhile, Young’s schema-focused cognitive therapy (Young, 1994), while drawing on some of Beck’s original theory and treatment methods has also introduced new interventions and has yet to be empirically validated. Similarly, the rational emotive behaviour therapy invented by Ellis (1962) and developed by Dryden and associates in the UK (Dryden 1995) has less supporting evidence.

This book aims to describe the basic principles of CBT theory and its related treatment methods. Most emphasis is placed on the cognitive therapy of Beck and colleagues (1976, 1979) and the British scientist—practitioners who have over the last 20 years significantly advanced the evidence base of CBT treatments for common mental health problems. A small sample of this vast literature, relevant to the disorders discussed in this book is as follows: in the field of anxiety disorders, Clark (1986), Freeston et al. (1996), Salkovskis (1989), Wells and Clark (1997). In depression, Fennell (1997), Gilbert (1992), Scott (1992), Teasdale (1993), Williams (1997). It is the work of these, mainly British, scientist– practitioners that has so greatly influenced the authors’ clinical work and thus forms the basis of the theory and practice described in this book. However, it is also important to acknowledge the significant contribution the behavioural psychotherapy tradition has made to the interventions described. Behaviour therapy would undoubtedly have been a central aspect of the clinical training of the scientist—practitioners named previously and was the initial psychotherapy training undertaken by the authors. This field includes the work of an earlier generation of researchers such as Gelder and Marks (1968), Marks (1987), Rachman (1980); and, in more recent times, Davey (1992) and Ost (1989). The book is written to encourage the reader to engage with CBT in the spirit of the scientist– practioner (Barlow et al., 1984; Salkovskis, 2002). This model encourages the clinician to approach their work with an enquiring mind and not only to use interventions that have been empirically established as valid using the scientific method, but to generate further research data by investigating the efficacy of their own clinical practice using the scientific method.

THE GENERIC COGNITIVE BEHAVIOURAL MODEL

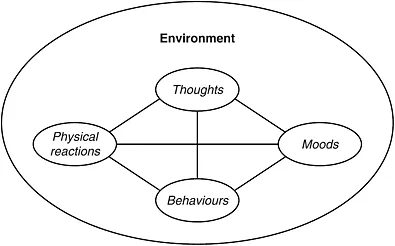

The starting point for making sense of CBT is to consider its generic principles. Thus, at a very basic level CBT looks at the inter-relationship between five elements: environment, thoughts, feelings, physical sensations and behaviour. This is usually described as a vicious circle and it is this metaphor that is used as a basic treatment rationale when first introducing patients to CBT as a model. In CBT, all disorder-specific models such as panic disorder (see Chapter 8), are presented as a vicious circle with these elements represented. The scientist—practitioner model would encourage the clinician, wherever possible, to use a disorder-specific model to introduce the patient to the CBT treatment rationale. This will be discussed later in the book.

However, in order to understand the fundamental principles of CBT it is useful to think about first principles. Thus, in its most generic form the CBT model can be represented, as it is by Greenberger and Padesky (1995), as a vicious circle connecting events in the environment with our thoughts, feelings, physical sensations and behaviour. This is illustrated in Figure 1.1.

THE THREE LEVELS OF THINKING (COGNITION) IN CBT

Within the CBT model there are three levels of thinking (in CBT textbooks this is referred to as cognition), which over the last 30 years have been defined, described and elaborated in a variety of ways. Key texts for the interested reader are by Beck and colleagues (1976, 1979) and Beck (1995) and Padesky and Greenberger (1995). The language used to describe these levels of thinking can seem complex and confusing to both clinician and patient. Therefore, here there has been an attempt to simplify the language and the following terms have been used to label the three levels of thinking:

- negative automatic thoughts (NATs)

- rules for living

- core beliefs.

From a theoretical perspective these three levels are connected and this is best explained using a metaphor. If we were to consider the three levels in terms of a fountain then the core beliefs would represent the powerful bore that forces the water out of the ground. The rules for living would represent the founts of water that directly emerge from the bore and give the fountain its form and shape. Finally, the negative automatic thoughts (NATs) would represent the hundreds of droplets of water that are thrown off as each fount, driven by the power of the bore, reaches its full height. Expressed in psychological terms the core beliefs represent our fundamental sense of self and are key to how we see ourselves, others and the world and are associated with high levels of emotion. The rules for living act as principles that guide an individual’s behaviour and govern how we act and interact in the world in a way that builds and further develops our sense of self, i.e. who we are. The NATs are the direct product of both our core beliefs and rules for living and represent how we make sense of our experiences in everyday situations. We will now consider each of these levels in more detail.

Figure 1.1 Five aspects of your life experiences (© 1986 Center for Cognitive Therapy, Newport Beach, CA)

First level: negative automatic thoughts (NATs)

The first level is usually referred to as negative automatic thoughts (NATs). At this level cognitive theory identifies two aspects to thinking:

- thought content, that is, what we think

- thought processes, that is, how we think.

These will now be considered in turn.

What we think: thought content

In Beck and colleagues’ model (1976, 1979) NATs are defined as an individual’s appraisal of a specific situation or event. As such this level of cognition represents what is going through an individual’s mind in a particular situation and may be associated with pleasant, unpleasant or neutral feeling states. Within the CBT model the NATs that the clinician is most interested in are those that are most closely associated with high levels of negative feelings such as anxiety, low mood, guilt, shame and anger and the like. Hence the use of the label NATs. NATs can occur in two forms:

- as words

- as images or pictures in the mind’s eye.

Each disorder-specific CBT model identifies different themes in terms of the content of NATs (and rules for living). Thus, for example, in panic disorder (Clark, 1986) the content theme in NATs is a catastrophic misinterpretation of bodily sensations where danger is imminent and typical NATs are:

- verbal or words, e.g. ‘I’m going to faint’, ‘I’m having a heart attack’

- an image or picture in the mind’s eye, e.g. image of self collapsing in the supermarket and people standing over you staring at you and not helping. Imagery is a key cognitive component of anxiety disorders.

How we think: information processing biases

In Beck’s original model (Beck, 1976; Beck et al., 1979; Beck et al., 1985b) these information processing biases are referred to as ‘thinking errors’ or ‘cognitive distortions’. Within Beck’s clinical model, the content of each NAT is said to contain information processing biases and particular types of information processing bias can be identified in relation to depression and anxiety. The most important ones are as follows.

When mood is depressed:

- thought processes are more negative and often focuses on past events: ‘I’ve never been good at my job’

- thought processes are more black and white: ‘if there’s any mistakes in that essay it’s not worth finishing’

- we have difficulty thinking in specific terms and tend to make overgeneralizations, using one specific incidence to jump to a general usually negative conclusion about ourselves, other people or events in our lives: ‘my boss didn’t like that work; he probably won’t like anything I do’

- we more easily recall negative memories from the past and it is harder to recall positive memories

- our thinking about past events can become ruminative, that is we turn the same thing over and over again in our minds repeatedly

- we are more much sensitive to criticism and see this where perhaps it is not intended, tending to take things personally whether they are meant this way or not.

When mood is anxious our thought processes are:

- more negative and often focuses on future events: ‘if I go for this interview I’ll make a fool of myself’

- automatically looking for what is potentially threatening or dangerous to us

- only focusing on the threat at hand with a narrow perspective and not taking in other information

- overestimating the risk in a situation

- underestimating the likelihood of our dealing with the situation

- focusing on the worst possible outcome often stretching weeks, months or years into the future

- dominated by worry about future events and we turn the same thing over and over again in our minds.

Generally, nowadays, these are referred to as information processing biases and this is the term the authors will use in this book. The categories defined by Beck in his original work are derived from clinical observation. Over the last 30 years ongoing research in the field of cognitive science has developed evidence to support Beck’s clinical observations and further elaborate how information processing biases maintain mental health problems. Examples of this research evidence exist (see Williams et al., 1997 for a comprehensive review) to support the idea that in anxiety and depression, how information is processed is biased in a way that means only certain types of information are taken on board or are given more attention and weight. These processing biases are viewed as central to the maintenance of emotional disorders by keeping the focus of attention on negative or threat-related information and not attending to or discounting contrary information. For an excellent text on the clinical application of this aspect of cognition, see Harvey et al., 2004. For example, staying with the cognitive model of panic disorder (Clark, 1986), there is research evidence (for an interesting discussion, see Barlow, 2004) to show that patients with panic disorder more readily detect and pay attention to changes in bodily sensations than non-anxious controls. Thus, if the panic prone individual experiences a sensation of light-headedness, they not only detect this more quickly than non-panic-prone individuals, but they are more likely to appraise this as dangerous and threatening and they will conclude ‘I’m going to faint’. They are more likely to do this than ignoring the sensation or ascribing a more benign explanation to the sensation, such as ‘it’s just a feeling, it will pass’. In the literature this is referred to as threat cue detection (Barlow, 2004; Williams et al., 1997) Similarly in depression, research evidence shows that not only is the content of thought negative but also a key processing bias that is central to the maintenance of depression is black and white thinking (see Williams et al., 1997).

Anxiety and depression are discussed separately here, however, in the reality of clinical practice where patients frequently present with comorbid anxiety and or depression then patients may experience a combination of these symptoms. This area represents the cutting edge of current CBT research. As the literature in the field of information processing biases and their role in the maintenance of mental health problems expands, some researchers are calling for the development of what is termed transdiagnostic models that take into account the clinical observation that these information processing biases are common across a range of anxiety disorders or in comorbid presentations of anxiety and depression. These information processing biases are discussed further in Chapters 8 and 9.

Patient example

Julie, who has a diagnosis of panic disorder, experiences panic attacks on a daily basis. When a panic attack happens Julie experiences a range of physical sensations including palpitations, breathlessness and dizziness. She perceives these symptoms as being dangerous and reports the following NATs that within the cognitive model of panic disorder (Clark, 1986) would be described as a catastrophic misinterpretations of the bodily sensations . Examples of these ...