- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Planning Under Pressure

About this book

Planning under Pressure offers managers, planners, consultants and students a comprehensive and authoritative guide to the Strategic Choice Approach, which has gradually been attracting worldwide recognition as a fresh, versatile and practical approach to collaborative decision-making under uncertainty.

Starting from basic principles, the book uses helpful diagrams and clear explanations to demonstrate practical ways of approaching daunting decision problems; of devising possible ways forward; and of working effectively towards agreed courses of action. Along he way, decision makers are helped to cope with diverse sources of uncertainty – technical, political, managerial – in a strategic manner.

In this extended third edition, the authors have added short contributions from 21 users from seven countries. These new contributors present lessons from their varied experiences in adapting the Strategic Choice Approach to guide decision-making and learning in settings ranging from the re-routing of a controversial city carnival procession to national policy for the management of nuclear waste.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Urban Planning & Landscaping1 Foundations

A PHILOSOPHY OF PLANNING

There are many ways in which it is possible to approach the challenge of planning in an uncertain world.

The approach to be introduced in this chapter is one in which planning is viewed as a continuous process: a process of choosing strategically through time. This view of planning as a process of strategic choice is, however, not presented as a set of beliefs which the reader is expected to embrace uncritically at this stage. That would be too much to expect – especially of an introductory chapter, which is intended merely to open the door for the more specific concepts, methods and guidelines to be offered in those that follow. People involved in any kind of planning activity of course build up their own sets of beliefs about the practice of planning in the course of their working lives: beliefs which they will not wish to set aside lightly. Yet experience in applying the approach offered here has shown that its fundamentals can usually be accepted without much difficulty by those planners or managers whose working philosophy draws more on their own practice than on taught beliefs. This is because, in essence, the approach sets out to do no more than to articulate, as clearly as possible, the kinds of dilemma that experienced decision-makers repeatedly face in the course of their work, and the often intuitive judgements they make in choosing how to respond.

In practice, such judgements may sometimes be accompanied by a sense of discomfort or even guilt. For the decision-makers may feel they are departing from certain principles of rational behaviour which they have been taught to respect. Indeed, the view of planning as strategic choice is found to offer more of a challenge to such idealised principles of rationality than it does to the intuitive judgements and compromises that seem characteristic of planning practice. If this point can be accepted, the reader should be able to relax in following the ideas put forward in this chapter and view them as offering perspectives that can help make sense of current practice – without necessarily demanding any revolutionary change in familiar ways of working.

THE CRAFT OF CHOOSING STRATEGICALLY

It is important to emphasise that the view of strategic choice presented here is essentially about choosing in a strategic way rather than at a strategic level. For the idea of choosing at a strategic level implies a prior view of some hierarchy of levels of importance in decision-making; while the concept of strategic choice that will be developed here is more about the connectedness of one decision with another than about the level of importance to be attached to one decision relative to others.

It is not too surprising that these two senses of the word strategic have tended to fuse together in common usage. For it is often the more weighty and broader decisions which are most obviously seen to be linked to other decisions, if only because of the range of their implications and the long time horizons over which their effects are expected to be felt. This, in turn, can lead to a view that any process of strategic decision-making should aspire to be comprehensive in its vision and long range in its time horizon, if it is to be worthy of its name.

| Planning Under Pressure: A View of the Realities |

But such a view of strategic choice can become a restrictive one in practice; for it is all too rarely that such idealistic aspirations can be achieved. The approach to strategic choice to be built up in this chapter is not only about making decisions at a supposedly strategic level. It goes beyond this in addressing the making of any decisions in the light of their links to other decisions, whether they be at a broader policy level or a more specific action level; whether they be more immediate or longer term in their time horizons; and no matter who may be responsible for them. This concept of strategic choice indicates no more than a readiness to look for patterns of connectedness between decisions in a manner that is selective and judgemental – it is not intended to convey the more idealistic notion that everything should be seen as inextricably connected to everything else.

So this view of planning as a process of strategic choice implies that planning can be seen as a much more universal activity than is sometimes recognised by those who see it as a specialist function associated with the preparation of particular sorts of plans. At the same time, it allows planning to be seen as a craft, full of subtlety and challenge; a craft through which people can develop their capacity to think and act creatively in coping with the complexities and uncertainties that beset them in practice.

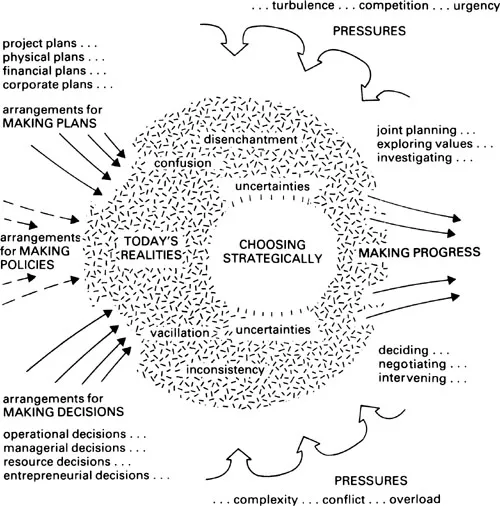

ORGANISATIONAL CONTEXTS OF STRATEGIC CHOICE

This relatively modest interpretation of the word strategic means that the view of planning as strategic choice is one that can be applied not only to decision-making in formal organisational settings, but to the choices and uncertainties which people face in their personal, family and community lives. For example, any of us might find ourselves involved in a process of strategic choice in addressing the problem of where and when to go on a holiday next year, or how to sell an unwanted vehicle, or how to deal with a difficult request from a relative or friend. Of course, the craft of choosing strategically becomes more complicated where it involves elements of collective choice – of negotiation with others who view problems and possibilities in different ways. Indeed, most of the more demanding problems to which the strategic choice approach has been applied have involved challenges of collective decision-making, either in organisational or inter-organisational settings; and this can have the effect of blurring many of the familiar distinctions of task and discipline around which organisational structures are usually designed. For the skill of choosing strategically through time is one that can become just as essential to the manager or executive as to those in more formal planning roles. This point is illustrated schematically in Figure 1, through which is presented a view of planning under the practical pressures of organisational life. It is a view in which an organisation's arrangements for making plans and those for making day-to-day decisions, tend to merge together into a less clearly bounded process through which progress is sustained. This is a process of choosing strategically in coping with difficult problems, amidst all the complex realities – or perceptions of reality – which contribute to organisational life.

The larger and more complex the organisation, the more it is to be expected that decision-making responsibilities will have become differentiated according to a multitude of operational, managerial or entrepreneurial roles. The more likely it is too that specialised plan-making functions will have been developed in an effort to maintain a co-ordinated, longer-term view isolated from everyday management pressures. However, no plan-making activity will remain valued within an organisation unless it can provide support for the more difficult and important of the decisions people face; and it is a common experience that carefully prepared plans can quickly lose their relevance under the pressures of day-to-day events. The combined pressures of urgency, competition for resources and turbulence in the world outside can soon lead to disenchantment and confusion in the arrangements for making plans; while the pressures of complexity, conflict and overload can lead to vacillation and inconsistency in the making of day-to-day decisions. To counter the resulting personal and organisational stresses, those responsible for organisational guidance sometimes look towards some over-arching framework of policies or aims. But, in practice, such policy guidelines can often be difficult to agree – especially when working in inter-organisational settings – and their contributions towards sorting out the predicaments of day-to-day management can be disappointingly small.

The making of generalised policies is therefore given its place in Figure 1; but it is not given pride of place. Instead, the emphasis is on the more subtle process of making progress through time by choosing strategically; and on the creative management of multiple uncertainties as a crucial means towards this end. And progress through time can itself take many forms. Immediate progress can take the form of intervening, or negotiating with others, as well as taking decisions on matters where direct action is possible. Meanwhile, progress in building a base for later decisions can also take different forms – not only investigations but also clarification of values and cultivation of working relationships with other decision-makers.

So the term ‘planning’ will be used in this book to refer generally to this more loosely defined process of choosing strategically, in which the activities of making plans, decisions and policies can come together in quite subtle and dynamic ways. But with a wide variety of ways of making progress to be considered, the process can soon begin to appear as one not so much of planning but of scheming – to introduce a term which has a similar literal meaning but which carries very different undertones in its everyday usage. Whereas the notion of planning may invoke a sense of idealism and detachment, the notion of scheming tends to suggest working for sectional advantage in an often devious way. So there is a case to be made that people involved in planning must learn to become effective schemers; and furthermore that it is possible to exercise scheming skills in a responsible way. Those who are troubled about social responsibility in planning – including both the authors of this book – may wonder whether there must always be a divide between responsible planners and irresponsible schemers; and, if so, whether it must always be the latter who will win. The concept of responsible scheming need not be considered a contradiction in terms. Indeed, it is towards the search for a theory and a practice of responsible scheming that the strategic choice view of planning can be said to be addressed.

It is, however, one thing for an individual to embrace a philosophy of planning as strategic choice; and quite another thing for a group of people working together to share such a philosophy as an unequivocal foundation for their work. Experience has shown that there are some settings where a sense of shared philosophy can indeed emerge – either where a set of close colleagues have learnt to work together as a coherent team, or where they discover that a common professional background allows them to proceed on shared assumptions as to how decisions should be made. Yet those whose work involves cutting across organisational boundaries must expect often to find themselves working alongside people with whom they do not share a philosophical base. So it is important to think of the philosophy presented in this chapter as a helpful frame of reference in making use of the more specific concepts and methods to be introduced in this book, rather than as a necessary foundation from which to build.

Indeed, it is a common enough experience, when working with strategic choice concepts, that people of quite diverse backgrounds can make solid progress towards decisions based on shared understandings, with little or no explicit agreement at a more philosophical level. Often it is only through the experience of working together on specific and immediate problems that they find they are beginning to break through some of the philosophical barriers which may have inhibited collaboration in the past.

DILEMMAS OF PRACTICE

The view of strategic choice presented in this book gained its original impetus from the experience of a particular research project, which offered unusually extensive opportunities to observe the kinds of organisational processes indicated in Figure 1.

The setting of this research was the municipal council of a major English city – Coventry – which, between 1963 and 1967, agreed to act as host to a wide-ranging project on the processes of policy-making and planning in local government, viewed as a microcosm of government as a whole. This seminal research was supported by a grant from the Nuffield Foundation, and has been more fully reported elsewhere (Friend and Jessop, 1969/77). Over the 4-year period, the research team was able to follow a wide range of difficult issues including the review of the city's first development plan; the redesign of its urban road network; the reorganisation of its school system; the renewal of its housing stock; the finance of public transport; and the scheduling of capital works. The researchers were able to hold many discussions with the various politicians, administrators, planners and professional experts involved, and to observe the processes of collective decision-making in which they came together – not only in the departmental offices and the formal meetings of Council and its committees, bu...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Contributors to Chapter 13

- Authors’ preface to the third edition

- Foreword to the third edition

- Authors’ preface to the second edition

- Authors’ preface to the first edition

- Foreword to the first edition

- A quick access guide

- 1 Foundations

- 2 Working into problems

- 3 Working towards decisions

- 4 Orientations

- 5 Skills in shaping

- 6 Skills in designing

- 7 Skills in comparing

- 8 Skills in choosing

- 9 Practicalities

- 10 The electronic resource

- 11 Extensions in process management

- 12 Invention, transformation and interpretation

- 13 Learning from others

- 14 The developmental challenge

- Access to further information

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Planning Under Pressure by John Friend,Allen Hickling in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.