![]()

1

Why Digital?

Introduction

Lasse Svanberg

The cinema – storytelling in a flow of consecutive images which meet in secret, poetic understanding – is an ancient artform, the celluloid film strip just its latest technical phase. Latest, not last. We will soon be filming without film and without tapes.

(Swedish film critic Bengt Idestam-Almquist, When Cinema Came to Sweden, published 1959)

This quotation is 45 years old, published at a time when the first 2 inch VTRs were introduced, revolutionizing the way television was made and transmitted. Yet – with incredible foresight – these few lines describe exactly where we are today. More and more feature films are being shot not on film, but on digital video media. At the same time videotape is beginning to disappear as a recording medium in the television industry (at least in news gathering), being gradually replaced by faster and more cost-effective hard disc and solid state solutions. And our need for ‘storytelling in a flow of consecutive images which meet in secret, poetic understanding’ is greater than ever before.

I recently retired from the Swedish Film Institute after 34 years of public service as ‘tech scout’, meaning that it was my responsibility to look ahead and inform others – through seminars and ‘Technology & Man Magazine’ (Teknik och Människa, T&M) – of what could be reasonably expected from technical developments in the near future, in terms of new work tools, methods and ideas for the production of moving images.

Nobody knows (or can know) with certainty on which media we will be shooting moving images 20 or even 10 years from now. The techno-cycles are getting shorter and shorter in the Digital Age, the lifetime of recording systems, standards and work procedures is being reduced. Let me therefore start by looking back. As Swedish poet Alf Henriksson said: ‘In order to know where we are going, we have to know where we have been.’

The History

‘The Digital Age’, how often have you heard this phrase during the past decade? When did it start? (And when will it end?) Most people seem to associate the Digital Age concept with the global breakthrough of the Internet and the World Wide Web (1995–2000) – the fastest breakthrough in the history of technical innovations. The film and TV industry, however, started its process of ‘digitalization’ when the first microcomputers arrived in the early 1980s, initially used for process control in film labs, lighting control in film studios and automatic control of animation cameras. Digital audio was introduced in the mid-1980s and the first digital VTR in 1989. LucasFilm presented its revolutionary EditDroid and SoundDroid in 1983. The first half of the 1990s brought with it an avalanche of technical innovation and radical changes in the form of (among others) digital offline non-linear editing and digital special effects, the latter creating digital SFX ‘factories’ in California which mass produced space monsters, intergalactic mass destruction, man-eating dinosaurs, earthquakes, tornados, fires and other natural catastrophes in a previously unseen image quality and quantity.

Film is Dead!

Cinematographic film has been declared dead many times in history, both as a recording and distribution medium. First, when television was introduced in the early 1950s. Why go to the movies when you can see moving pictures in your own living room – for free (in the United States)! Then when portable professional VTRs became available. Why shoot on film when you can shoot on videotape and immediately see what you have recorded?

In 1972 I went to Hollywood to make a special issue of T&M Magazine on ‘Video Film’ (that was at the time when Vidtronics were big on videotape-to-film transfers). I met, among others, the legendary Director of Photography Lee Garmes (one of the DoPs on Gone With the Wind), who had just finished shooting his first feature on videotape, Why? (a suitable title since film transfers looked pretty bad at that time). Garmes stated, without hesitation: ‘I hope I will never see a piece of film again.’

‘Film is dead!’ was cried out even louder when home video hit the market in a big way in the early 1980s.Why go to the movies when you can rent VHS cassettes of all new films, for less than the price of a cinema ticket and in a gas station or videoshop near you? Yes, it killed large numbers of smaller cinemas in suburbs and in the rural communities, but the cinema industry as a whole prevailed.

When the Japanese launched analogue HDTV in the late 1980s, American director Francis F. Coppola became so enthusiastic over the HDTV-to-film transfers he saw in Tokyo that he went home to San Francisco and created an all-electronic film production system named SLEK (So Long Eastman Kodak). His company went bust while Eastman Kodak still thrives (although eagerly diversifying into the digital domain). The HDTV-to-film transfers, however, looked quite good, good enough to make raw stock manufacturers a bit worried. HDTV was, however, analogue at that time, which turned out to be a very expensive cul-de-sac for the Japanese and European electronics industry, and it took almost 10 years before a somewhat sustainable digital HDTV alternative was presented as a feature film recording medium. Sony and Matsushita bought a major part of the Hollywood studios (Columbia and Universal) in the mid-1990s and ‘hard-sold’ HDTV-based film production techniques to Hollywood filmmakers. Unsuccessfully. It was only George Lucas who at that time did not want to see a piece of film again.

Why then has a ‘stone age’ technology like the photo-chemical film process managed to survive all these attacks from the electronics industry?

• Film has, for more than one hundred years, been a well-established world standard both in production, distribution and exhibition (and there are no real world standards in the world of electronics).

• Film history has also set the standards for screen-writing, storytelling techniques and dramaturgy.

• Cinema film is still the waterhole that attracts the biggest creative buffalos (and a few hyenas), because of its superior audiovisual impact (the large screen, the captive audience) plus the international glamour and artistic prestige which still characterizes the elite in the film industry, both on national and international levels.

• Cinematographic film still holds the lead as a recording medium in terms of resolution power and is furthermore far superior as a medium for long term archiving with its guaranteed lifetime of up to 500 years (properly stored).

‘The Incredible Shrinking Game’

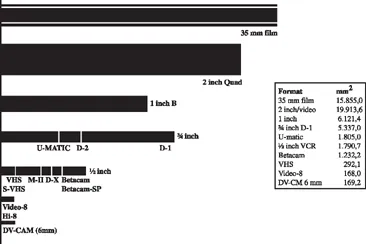

The technical developments during the past two decades have meant tremendous improvements in information packaging density and in reduction of the size of equipment. It is clearly visible in Fig. 1.1A, showing the area (in square millimetres) which one second of images and sound occupy on different information carriers, from 35 mm film and 2 inch videotape to 6 mm mini-DV videotape.

The reduction of equipment size, price and manning requirements have been especially dramatic in the television industry, as Table 1.1 and Fig. 1.1B (an almost outrageous simplification of a very complicated and 35-year-long process) show.

Fig 1.1 Area required (in mm2) to carry one second of images in different video formats and 35 mm film (Copyright T&M Magazine 1998; reproduced with permission).

Let us hope the future does not hold 0.5 man teams (although it would be considered progress by broadcast TV economists). For someone like me, who shot my first feature film in 1966 with a blimped Arriflex 35 mm camera (weighing some 20 kilos) it is actually ‘mind-blowing’ that you can today record images and sound of broadcast quality (even acceptable on the big cinema screen) with a camera that almost fits into your jacket pocket, costs no more than 3000 Euro and has built-in ‘Steadicam’. I am quite surprised that this new possibility has not changed the structure of the big broadcast TV dinosaurs more than it has. Powers of inertia, I would guess; or the old German saying at work, ‘Why make it simple, when it can be made so wonderfully complicated!’

Table 1.1 Approximate weight of equipment, minimum manning requirements and price of equipment for the acquisition of location shots in broadcast quality

| Year | Format | Weight (kg) | Manning | Price (Euro)* |

| 1960 | 2 inch videotape | 200 | 10 | 300 000 |

| 1975 | ¾-inch videotape | 20 (back-pack) | 4 | 40 000 |

| 1995 | ½-inch Beta tape | 10 | 2 | 30 000 |

| 2004 | ¼-inch (6 mm) DV tape | 0.5 | 1 | 3 000 |

* Ball-park figures.

When it comes to digital feature film production do not forget that a fully equipped and film-styled HD (high definition) video camera is just as bulky as a blimped 35 mm film camera, even bulkier if you count in the large HD monitor in the package. HD camcorders will, however, decrease in size and weight in the near future.

Silver or Rust?

The ‘video vs. film’ debate accelerated in the early 1990s. In 1995 I received an SMPTE award and the ceremony was preceded by a presentation by Lawrence Thorpe, a very powerful speaker, on Sony’s latest video camera marvel and its merits as a new filmmaking tool. Since I was the first award recipient I could not resist the temptation of turning to him (at the end of my acceptance speech) and observing that ‘fifteen years of experience as a DoP tells me that the really important thing is not what you’ve got in the camera – film or video, silver or rust – the important things is what you’ve got in front of and behind the camera’. This was followed by a dead silence and I asked myself, what have I said? Then one person started to applaud and another joined in, out of a crowd of some two hundred (probably the only two DoPs present!).

I still haven’t figured out if the silence was an expression of disapproval or total lack of understanding. A brutally simple conclusion would be that motion picture and television engineers (mostly grey-haired men) have no interest in what happens in front of and behind the camera, they are only interested in the camera itself and the engineering beauty in the technical parameters of the recording system connected to it. Why otherwise would the electronic ‘film style’ cameras that appeared at the end of the 1990s have looked the way they did?

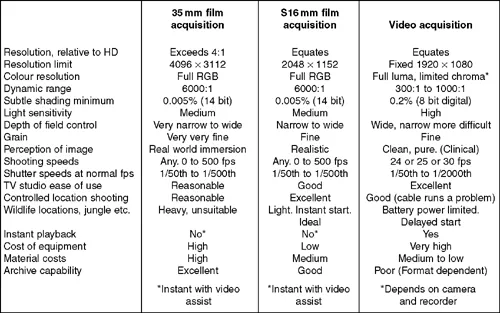

Silver or rust? I have seen dozens of comparisons between film and video as production media, most of them biased on the silver or rust side. One of the most thorough, by Peter Swinson, appeared in the February 2004 issue of the British Image Technology magazine (BKSTS), comparing 35 mm, Super 16 mm and HD video acquisition (Figures 1.2, 1.3). I leave it to you to decide whether it is objective or not. In my opinion it is not very flattering for the video alternative, especially combined with Peter Swinson’s complementary figure comparing image areas and resolution (in Ks) for film and video shooting formats.

Fig 1.2 Silver or rust? Relative merits of film and HDTV (Copyright: Peter Swinson, 2004; reproduced with permission).

Three milestones

Before dealing with the present, I would like to point out three milestones in digital film production from the near past.

Toy Story was released in 1995 as the first film ‘shot entirely in cyberspace’. It was entirely computer animated by Pixar and John ...