![]()

1 | Organization and Architecture |

THIS BOOK IS ABOUT INNOVATION and the innovation process, particularly the development of innovative new products. What is innovation? Many decades ago, Joseph Schumpeter offered a now-classic definition of an innovation as something new or improved. Specifically, he defined innovation as the new combination of productive means as follows: (1) the introduction of a new good—that is, one with which consumers are not yet familiar— or a new quality of a good; (2) the introduction of a new method of production; (3) the opening of a new market; (4) the conquest of a new source or supply of raw materials or half-manufactured goods; or (5) the new organization of any industry (Schumpeter 1934).

A far simpler definition is offered by Stephan Schrader (1996). He defines the term by drawing the distinction between an invention and an innovation. Taking off from this, imagine a picture of a small town somewhere in the Wild West of America in the mid-nineteenth century. In the center is a railroad, Schrader’s example of the invention of the time. But it is only an invention. Taking the analogy further, he argues that we don’t know where the railroad goes. We can only guess at the unknown region to which it might travel. It is an invention that represents some technical progress, but it is not in and of itself an innovation.

In 1883, the director of the U.S. Patent Office declared that the office “may well be closed since all the important discoveries have been made.” He, too, spoke of inventions, not innovations, but Schrader uses this to get us closer to a definition of innovation.

This was a small error, because a few years later, in Europe, a patent was filed for an invention that has probably had an impact unlike any other in our lifetime: the automotive engine.

But just as the director of the U.S. patent office had erred, so too did Carl Benz and Gottlieb Daimler underestimate their invention. They assumed that the motorcoach would replace the horse-drawn carriage. But they never assumed that the automobile would transform our way of life. (Schrader, 1996, p. 5)

Benz and Daimler failed to realize the impact of the motorcoach because they thought about it only as an invention, not as an innovation. It is an important distinction because it speaks directly to the question of whether the innovation process can be planned—a central aspect of our discussion in this book.

Innovation is invention and application. Or, put differently: innovation is invention and exploitation. Thus we come to the question posed: can innovation be planned?… Planning now refers to two dimensions. The first is the dimension of the invention. Can one plan an invention? Can one predict the directions in which scientific knowledge and technical progress will develop? Second is the application of the invention. Can one predict the purposes for which an invention can be used and how the invention will become important?…

Just about each invention had been anticipated, perhaps not 100 years in advance, but certainly at least a few years or even decades before, as in the case of the atomic bomb or the microchip.

So, here planning is possible, even if one cannot forecast the precise day or year when the appropriate breakthrough occurs…. Predictability thus exists to the extent that the probability of certain inventions can be accelerated by resource deployment and favorable basic conditions. (Schrader, 1996, p. 6)

Another invention—the personal computer—shifts the focus of the question and raises another issue that figures prominently in our book: namely, the role of uncertainty in the innovation process.

Suddenly, the focus is no longer on the technical invention, but the use of the invention is at the center. Hence, it is about its exploitation, its utilization…. And so we are into the domain of innovation, where the largest unpredictability exists: the domain of an invention’s utilization. Humans use their inventions differently than planned…. In the 1940s, one could probably foresee the enormous potential for efficiency with computers. No one counted on computers being used later for keeping recipes or as gaming equipment for children and adults….

The planning of innovations has two dimensions: the invention and its utilization. One thinks, intuitively, that it is with the invention that major uncertainty lies. But that is not correct at all. Big, basic uncertainties often exist with respect to utilization. Technical progress is still relatively foreseeable. The employment of an invention is substantially more difficult to predict.

Now let us look at how this works out in practice. What is actually planned in the context of innovation management? Here you may be surprised. Enterprises have relatively good capabilities when it comes to forecasting technological developments. There is a systematic monitoring of technology, watching of trends, and so on. This technicians manage. They appreciate inventions….

But we have neglected the innovation process. We ask, therefore, the final question: Can innovation processes be planned? For the operations manager, this is a major challenge. We can steer and arrange processes quite well that we understand. But an innovation is different. It is tied to the creation of something new. It is difficult to define tasks because we do not yet know which ones will be required….

We have learned that innovation covers two activities: the invention and its utilization. Both activities are not completely plannable, but this is more so with respect to utilization than with invention. We learn from this that despite the difficulty of planning, it is incorrect to conclude that the innovation process cannot be managed. (Schrader, 1996, pp. 6–7)

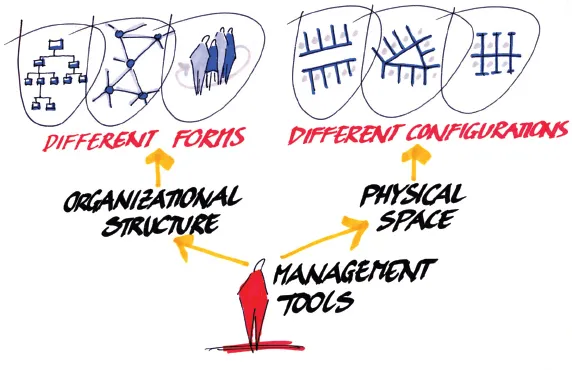

We show that both organizational structure and space are tools that can be used to manage the innovation process, as illustrated in Figure 1-1.

Every organization has a spatial dimension, and most space has an organizational dimension. People organize themselves to get things done and need space within which to do those things. We think in terms of space, and space takes on its real meaning by virtue of how it is used. Both organizational structure and space influence the interaction patterns among people, which are central to the innovation process. Bring the two together, and the manager has a better, more effective way of structuring interaction patterns that lead to innovation.

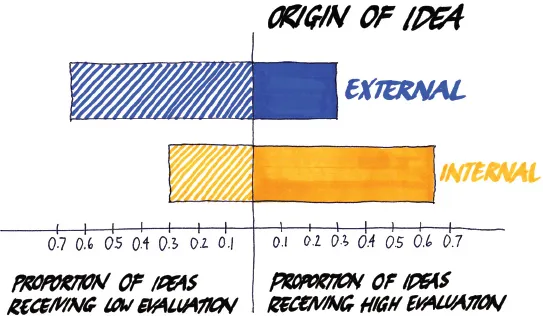

Much of our discussion focuses on communication1—for a very simple and direct reason. Earlier research by one of the present authors (Allen 1984) shows clearly the critical nature of internal technical communication in the new product innovation process. Innovation depends on invention and ideas, and this and other research finds consistently that the best source of new technical ideas for product development engineers is a colleague in the same organization (Figure 1-2).

This rich source of ideas is significantly underutilized. Why? The research highlights many reasons, paramount among them being a simple lack of awareness. In large organizations, the staff is frequently unaware of the diversity of talent among their coworkers. We have heard so many stories from so many different people of how they searched far and wide for someone with a particular type of knowledge only to find that the right person was working within their own organizations, perhaps in an adjacent building. This is one important aspect of awareness, among several others, that we address.

As products grow in complexity, their development requires the efforts of larger numbers of people. These efforts extend well beyond the engineers or scientists who are assigned directly to product development; many others support the development through formal and informal consulting and contribute knowledge and ideas to the members of the development team. Given this need for additional technical support, it becomes essential to realize the maximum benefit from the communication processes within product development organizations.

The recognition of this need launched an extended program of research directed toward improving our understanding of what governs technical communication in organizations. We quickly uncovered three factors that determine the structure of technical communication networks in organizations. The first is the structure of the formal organization, which is reflected in organizational charts. We group people in organizational units (the boxes on a typical organizational chart) because we believe that communication among them will be productive. The second is the physical structure and layout of the facilities in which the work is performed, which brings us into the realm of architecture. The third is the structure of informal relations, sometimes referred to as an informal organizational structure, that develops among any set of people working in the same part of an organization or in proximity of one another.2

In all of these technical communication structures, awareness is important. In fact, awareness is a critical factor in the innovation process because of how the nature of work has changed and the impact that knowledge now has on work.

A century ago, the impact of knowledge on work was quite different. The typical organization had a division of labor; the work of its employees was divided into multiple parts. The results of each person’s work were simply added together to create the resultant product. Only the bosses—foremen and executives—required the knowledge that allowed for a complete picture of the work. Individual workers did not need to know much more than what was specific to their individual tasks to complete their jobs.

Today, in the innovation-driven organization, the resource of knowledge is required in the work of nearly everyone. The results of each individual’s work are not brought together at the end of a linear process, but are communicated throughout the process. Further, with respect to the product development process itself, growing numbers of people are involved in generating ideas and bringing those ideas together. Innovation is complex and unfolds in many steps, both big and small. Everyone must be up-to-date with respect to information, and all must coordinate their work—both of which impose on the organizational structure in a variety of ways. The dispersion of knowledge has been greatly aided by the ability to communicate information and knowledge via the Internet and by other rapid means. But these technological tools do not themselves resolve the challenges of managing the innovation process.

Innovation today results from collaboration and collective intelligence. The innovation process transcends individuals and transcends departments, with knowledge emerging within multiple disciplines. To succeed, it requires organizational structure for the sharing of knowledge and for inspired communication to unfold in real time, and the space that makes it possible. The organizational structure must be flexible to allow for the interactions that matter, and the space too must be supportive. They ...