![]()

Chapter 1

What Is Formal Ethics?

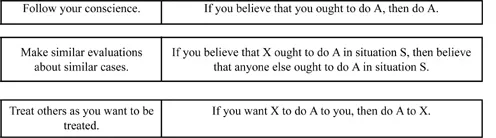

The goal of moral philosophy is to help us to think better about morality. In pursuit of this goal, philosophers sometimes appeal to formal principles like “Follow your conscience,” “Evaluate similar cases similarly,” and “Treat others as you want to be treated.” This book is about such principles.

Formal ethics is the study of formal ethical principles. It tries to formulate such principles clearly (and without absurd implications), organize them into a defensible system, and show how they can help us to think more rationally about morality.

Our first task is to clarify the distinction between ethical principles that are formal (like “Follow your conscience”) and ones that are material (like “Don’t steal”). Is there a clear distinction here? How can we draw the distinction? To answer these questions, I’ll first explain the notion of a formal logical principle; then, by analogy, I’ll explain the notion of a formal ethical principle.

1.1 Formal Logical Principles

Formal logic is the study of formal logical principles.

Philosophers have disputed this argument for many centuries:

If God doesn’t want to prevent evil, then he isn’t all good.

If God isn’t able to prevent evil, then he isn’t all powerful.

Either God doesn’t want to prevent evil, or he isn’t able to.

∴ Either God isn’t all good, or he isn’t all powerful.

Practically every aspect of this argument is controversial: the plausibility and truth of each premise, the interpretation of key terms, the usefulness of arguing such matters, and so forth.

As far as I know, there’s been no dispute over whether the conclusion follows from the premises, that is, whether the argument is valid. Rather, the dispute has focused on the premises. The validity is clear. If we had doubts about this, we could work it out (using the logical machinery from any logic text)—as we work out a multiplication problem to check the answer.

Our argument is valid because its form is correct. We can express its form by using variables, which are letters that abbreviate phrases. Here’s the form in English and in symbols:

| If W, then G | |

| If A, then P | |

| Either W or A. | |

| ∴ Either G or P. | |

These use statement variables (like “W” for “God doesn’t want to prevent evil”) and logical terms (like “if-then”). The result is a formal logical principle—a principle of inference expressible using only variables and logical terms. Formal logic studies such principles.

The variables and the logical terms change between systems. In prepositional logic, the variables stand for statements and the logical terms are “if-then,” “and,” “or,” “if and only if,” and “not.” With syllogisms, the letters stand for general terms and the logical terms are “all,” “no,” “some,” “is,” and “not.” Quantificational, modal, and deontic logic bring more changes.

Formal logical principles are correct (valid) or incorrect (invalid). Most beginners at logic are poor at distinguishing the two;1 but the experts largely agree. We can generally show incorrect principles to have clearly absurd instances. Consider the fallacy of affirming the consequent (on the left):

| If A then B. | If I’m in Texas, then I’m in the US. |

| B. | I’m in the US. |

| ∴ A. | ∴ I’m in Texas. |

This principle is wrong, since it lets us infer false conclusions from true premises—as on the right. Here both premises are true; but the conclusion is false, since I’m in Chicago. So we reject the fallacy as leading to absurdities.2

The appeal to concrete instances generally shows whether a logical principle is correct. We test a principle by trying to demolish it, and reject it if we find absurd instances. We accept it (at first tentatively) if we look hard and find only acceptable instances. We may later develop further methods to check validity.

Philosophers of virtually all viewpoints accept roughly the same principles of logic.1 These philosophers may use wildly different premises and conclusions; but disputes over validity—whether the conclusion follows from the premises—are rare.

A few logical principles are disputed. Logicians differ, for example, on the validity of this inference:

| It’s possible that it’s possible that A. | |

| ∴ It’s possible that A. | |

Other logical disputes deal with the law of the excluded middle; classical logic versus intuitionist and multi-value logic; standard quantification versus free logic; conflicting modal systems (especially T, B, S4, and S5); and the Barcan modal formulas.

These disputes have little impact on philosophical arguments. I counted 178 such arguments (most from actual philosophers) in my Symbolic Logic textbook (Gensler 1990). Only five of them (3 per cent of the total) depend for their validity on controversial principles.2 Disputes over logic seldom make a difference to the validity of our arguments.

Disagreements intensify when we ask about the meaning and justification of logical principles:

■ Is logic about sentences or about abstract entities like propositions? What kinds of things are true or false? What is truth?

■ What does valid mean? Does it mean that it’s logically impossible for the premises to be true while the conclusion is false? Does logical impossibility make sense?

■ What is the scope of logic? Does logic include set theory? Is there a “logic” of imperatives only in an extended sense?

■ How are the basic principles of logic to be justified? Do they express metaphysical truths about reality? Or language conventions? Or self-evident a priori truths? Or empirical truths?

Such issues fall, not under logic, but under philosophy of logic.

The ultimate basis of anything—even logic—is controversial. What is the meaning and justification of my claim that this is a pencil? That there are other conscious beings? That there’s a God? That Hitler acted wrongly? That 5+7=12 ? That our basic logical principles are valid? Such questions raise endless battles. Even logic isn’t exempt from disputes over foundations.

“Foundations” suggests the image of a basement that needs to be built before the rest of the building. Until we build the foundation, we can’t do logic or ethics (or math, or science, or religion). A different image is that we already live in the building, find it secure, and needn’t worry about what supports it. Foundational questions are unhelpful speculations.

Both images are misleading. Foundational questions influence practice and are important in their own right (since the unexamined life isn’t worth living), but they’re highly speculative. We can do logic or ethics without resolving the foundational issues; but we could probably do them better if we resolved the issues.

To sum up:

■ Formal logical principles are largely uncontroversial. We can test such principles by searching for absurd instances.

■ We have to fudge the previous statement somewhat, since there are genuine disputes over formal logical principles. But these disputes touch few of the arguments that we use.

■ The philosophy of logic (about the meaning and justification of formal logical principles) is very controversial.

1.2 Formal Ethical Principles

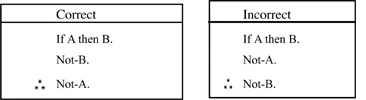

Formal ethics is modeled after formal logic. Formal logic studies formal logical principles—principles of inference expressible using only variables and logical terms—like modus tollens:

Similarly, formal ethics studies formal ethical principles—expressible using only variables and constants1—where the constants can include logical terms, terms for general psychological attitudes (like believe, desire, and act), and other fairly abstract notions (like ought and ends-means). We can express our earlier examples using only variables and constants:

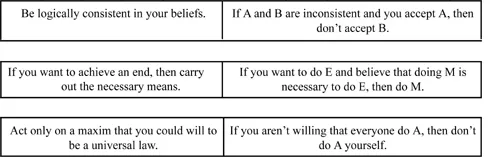

Material ethical principles (like “Don’t steal”) can’t be analyzed this way, since they contain concrete terms (like “steal”). Here are some further formal ethical principles:

These variable-constant formulas are crude and lead to absurdities if taken literally. We’ll refine the formulas later.

If my analogy with formal logic works, we’ll find that:

■ Formal ethical principles are largely uncontroversial. We can test such principles by searching for absurd instances.

■ We may have to fudge the previous statement somewhat.

■ Metaethical issues about th...