![]()

1

Introduction

what is ‘development’?

[D]evelopment is a continuous intellectual project as well as an ongoing material process.

(Apter, 1987: 7)

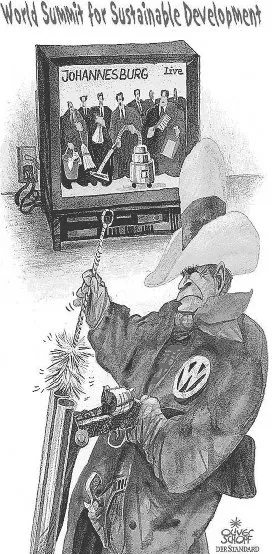

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, a number of high-profile events and processes have illustrated that the challenges of global ‘development’ are becoming an increasingly important part of international relations and world politics. After the terrorist attacks on the United States in September 2001, many people were quick to point out that poverty and inequality between nations was becoming the most important issue in building world peace and international political stability. In the context of the global war on terrorism that has followed 9/11 and the international concern to rebuild and reconstruct Afghanistan and Iraq, issues of poverty and development have again taken centre-stage. Furthermore, in the spring of 2002 at a United Nations (UN) meeting in Monterrey, Mexico, world leaders made many promises to deliver more aid and assistance to poor countries and to open their markets to trade with the ‘lesser developed world’. At the time of writing, the World Summit on sustainable development is meeting in Johannesburg (South Africa) to discuss current trends in global production and consumption and the social and environmental strains that threaten to ‘derail development efforts and erode living standards’ (Wolf-ensohn, 2002: 21). What is particularly interesting about these and similar world gatherings is that they bring together nations and peoples with often vastly different and incredibly varied levels of social and economic resources for ‘development’ to discuss common approaches and to devise collective solutions. The United States and Uganda, for example, are characterised by marked differences in living standards, with very different cultures and histories as well as often divergent perspectives on how to change the world economy and how to devise policies that improve economic growth opportunities for all peoples. In seeking to understand these kinds of differences between the ‘rich’ and ‘poor’ nations of the world, geography and geographical analysis have a particularly important role to play.

One of the major difficulties in finding common approaches, policies and solutions to these challenges is that the idea of ‘development’ is difficult to define, since the term has a whole variety of meanings in different times and places. In Malaysia, for example, debates about the nature of development and its importance to national ‘progress’ and social change have taken on a very different complexion when compared to a country such as South Africa or Sri Lanka. Even within such countries, the meanings and definitions of ‘development’ vary substantially across national territory and between different social groups or are, in a way, ‘place-specific’. As if to complicate our study of ‘development’ and its geographies even further, it might be said that the term actually has no clear and unequivocal meaning and is in a sense truly the stuff of myth, mystique and mirage. Little consensus exists around the meaning of this heavily contested term yet most if not all leaders of the world's many nation-states and international organisations claim to be pursuing this objective in some way. This book seeks to show that, by contrast, the strength of the term comes directly from its power to seduce, to please, to fascinate, to set dreaming, but also from its power to deceive and to turn away from the truth (Rist, 1997:1). Development is nearly always seen as something that is possible, if only people or countries follow through a series of stages or prescribed instructions. It is also often assumed that an organic and inherently ‘natural’ process of evolution is somehow at work, one that is both progressive and forward-moving. The assumption here is that from little acorns do giant oaks grow. Development also often means simply ‘more’: whatever we might have some of today we might or should have more of tomorrow (Wallerstein, 1994). In this book we will be delving further beneath the surface of these different definitions in an attempt to show how they have often been ‘normative’ (saying what should be done) or instrumental (serving as an instrument or means), usually pointing to things that are lacking or deficient (e.g. knowledge) or things that need to be intensified (e.g. democracy). As we shall see, at the core of development studies and also development geography there has been this very normative preoccupation with the poor and with what are often referred to as the ‘marginalized and exploited people of the South’ (Schuurman, 2001: 9).

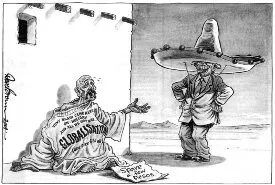

Figure 1.1 The World Summit for Sustainable Development as ‘seen’ on TV by President Bush

Source: Oliver Schopf and CWS

The term ‘development’ often refers simply to vague notions of ‘good change’, an unquestionably positive phrase that in everyday parlance is practically synonymous with ‘progress’ and is viewed typically in terms of increased living standards, better health and well-being and other forms of common good which are seen to benefit society at large. The core definition of development in the United Nations Development Programme's annual Human Development Reports revolves around the idea of an ‘enlargement of people's choices’. The term is used regularly in a wide variety of senses however, which embody ‘competing political aims and social values and contrasting theories of social change’ (Thomas, 2000: 23). Thus conflicting and contradictory views about the relationships between development and capitalism can be enfolded within popular assumptions about positive change and how to bring about poverty eradication.

A number of the major development agencies have recently tried to demonstrate that both ‘developing’ and ‘developed’ societies can be rank ordered according to common measures of progress and change such as in the case of the UN's Human Development Index (HDI). This tried to escape the limitations of previous measures by combining four variables for each country: income, life expectancy, human liberty and level of education. The definition of poverty (like that of development) remains hotly contested however, while conditions of poverty clearly vary between different areas of the world, as does the way poverty is experienced, making it more difficult to reach a ‘universal’ definition that can be agreed upon. Poverty is of course a relational issue which refers to life chances and experiences which are uneven socially and spatially, but debates about poverty have generally focused on those groups that are ‘deprived’ and lacking in social power, assets or capital rather than focusing on the associated issues of wealth and consumption. Moreover, poverty is clearly far from being a new concern, but ‘development’ is an idea that has acquired particular meanings over the past two centuries, especially since the end of the Second World War.

Figure 1.2 Fifty years of successful UN operations?

Source: UN Department of Public Information

The vision of development articulated by many global agencies however is still very much based around the idea of a linear progression, indicated as different degrees of departure from already established western ideals and experiences. As in the case of Gross National Product (GNP) per capita, the HDI does in many senses (albeit at a very crude level) point to growing gaps between ‘rich’ and ‘poor’ areas and peoples of the world, but their significance is almost cheapened by the failures of these ‘generalised’ indicators. Too often these ‘gaps’ are taken as a given in the study of development and rarely is this sufficiently problematised or questioned in studies and representations of poverty which may therefore even be responsible for deepening, reproducing and widening these gaps (Rist, 1997). None the less, even though the data give only a shallow and sometimes misleading impression, it is still possible (and necessary) to theorise about different levels of economic development in the twenty-first century (Peet with Hartwick, 1999: 9).

Figure 1.3 To what extent does the United Nations create a better world?

Source: UN Department of Public Information

Figure 1.4 Western political leaders like Tony Blair have a very positive view of globalisation

Source: © Dave Brown 2001, The Independent

In many western societies, poverty is now often considered in relative terms, where the wider social exclusion of the poor is sometimes taken into consideration. This notion of poverty is also relevant in non-western contexts where a wide range of social ‘resources’ may be available to an individual other than monetary income (Sen, 1983, 1985). None the less, it is argued here that despite some of these changes, the measures adopted by many global development organisations remain powerful examples of precisely how not to go about counting the poor (Reddy and Hogge, 2002). This book seeks to show that people experience impoverishment in and through their particular places and localities. This also needs to be considered as an important dimension of poverty in a global and inclusive definition, which does not seek to ‘objectify the poor’, to declare them a ‘problem’ and to invent a solution, but rather to convey the variety of complex daily struggles that poverty involves on a number of geographical scales, from the local to the global. What is particularly intriguing here is that despite nearly six decades of ‘global’ strategies of development, few if any of the international agencies know exactly how many poor people there are in the world and only very recently have these agencies actually begun to ask: How do poor people themselves view issues of poverty, development and well-being? (Narayan et al., 2002).

As we shall see, the notion of development thus represents a great variety of definitions, theories and approaches, but it can also be considered something of a hosting metaphor that contains within it ‘crucial connecting assumptions between growth and democracy’ (Apter, 1987: 7). In the chapters that follow we will be exploring the ways in which development also often serves as a heuristic device, as something to stimulate thought or discussion, a way to propose strategies, theories and ideologies of how to overcome and eradicate poverty. Before we set out on this journey it is worth remembering that development is one of the most complex words in the English language and its varied intellectual history or genealogy can confuse and limit its contemporary usage in myriad ways (Williams, 1976).

PEOPLE, PLACES AND PROGRESS: THINKING SPATIALLY ABOUT DEVELOPMENT

This is the power of development: the power to transform old worlds, the power to imagine new ones.

(Crush, 1995: 2)

One of the most intriguing and useful discussions of the meaning and significance of development was written in 1997 by Majid Rahnema, who once served as a minister in the government of Iran in the 1960s and later headed a UN development programme in Mali before engaging in debates about ‘alternative’ development in his later career:

I remember very well that, for example, in my own country, dozens of researchers have set out to find an equivalent term in Persian. There were many concepts that spoke of “good life”, “solidarity”, “prosperity”, “blossoming”, “the happiness of living together”, and “the beneficial flow of life”. These words were far from hollow, fossilized or pompous.

(Rahnema, 1997a: 6)

Rahnema is referring to the political and economic climate of the 1960s when Iranians searched for an equivalent term in Persian. ‘Dozens’ of researchers have since set out to understand how the idea of development could be made relevant to their particular historical and geographical contexts. In particular, Rahnema recalls how, in the case of the Arab and Persian world, the term frequently acquired and was imbued with these positive characteristics while debates around the meaning of ‘development’ were far from empty or ‘hollow’: ‘they stirred people's hearts, spoke to them, resonant as they were of everything that gave meaning to their dreams and the well-being of a happy community’ (Rahnema, 1997a: 6).

Thus, while the Middle East does not usually figure prominently in debates about global development, Rahnema shows how the meanings of development in the Iranian context also stirred people's hearts, dreams and imagination. This raises fundamental questions about the relations between people and places that we need to examine further. Debates about development have resonated with people and communities in a variety of places and spaces around the world over a long period of time. One objective of this book is to formulate a view of development which focuses on the relationships to households and communities and not only (as often happens) on ‘formal’ institutions such as the state, the transnational corporation, the international development agencies or non-governmental organisations (NGOs). This is a very difficult balance to maintain consistently, since development operates across so many spatial scales and involves different degrees of formality simultaneously.

Geographers have often focused on deprived and poor areas and have raised questions about different regions and inequalities, adopting a range of different approaches over the past six decades. What we will focus attention on in this book is the interactions between different spaces and places and the ways in which these interactions have been stretched and extended at different times and through different processes. In this sense, our consideration of space, place and scale can offer alternative organising principles around which to think about development. In particular this book is aimed at intermediate and advanced level undergraduate students studying development, and on one level it sets out to offer a thematic and historical critique of development, arguing that we thus need to understand the variety of relationships between people and places by examining historical relationships at the global level. On another level, it is argued that such an exploration needs to be grounded, to be seen as rooted in the ‘everyday’ practices, movements and behaviours of individual people based in particular places.

It is worth remembering that there is also no easy definition of place here, since we are referring to such a complex diversity of peoples, cultures and localities. Places are not bounded however, but are ‘open’ and linked to a ‘space of flows’ and they can also be seen as something that is ‘made’ by the media or understood as a context for social and political relations (Holloway and Hubbard, 2001). People and places have all too often been disregarded in the rush to form grand theories of econ...