- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Stuart England

About this book

Stuart England is an invaluable introduction to the political, religious and social history of seventeenth-century England. It provides a wide-ranging and lively account of core events, drawing on both contemporary sources and the latest interpretations by modern historians.

Starting with the legacy of Elizabeth I, and ending with the reign of William III and Mary. Stuart England covers all aspects of the monarchy, high and low politics and the culture of the people. Key topics include:

* English society and religion

* ideas of monarchy and government

* finance and parliament

* foreign policy

With comprehensive questions and analysis, exercises, diagrams and maps,Stuart England provides an excellent and indispensable guide to English history of the seventeenth century.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 The Stuart inheritance

In 1603, James VI of Scotland inherited the throne of England from his cousin, Elizabeth I. Although he had enjoyed a relatively successful reign as King of Scotland, his new kingdom presented quite a different set of challenges. England was larger, wealthier and more heavily populated than Scotland, and was a far more significant player on the international stage. It also differed significantly in its religious, political and economic make-up. James was fully aware of England’s relative wealth, a prospect that he apparently relished, likening himself to a ‘poor man’ who had finally arrived in ‘the land of promise’. However, in order to provide his subjects with effective government, he would also need to develop an understanding of other aspects of England’s make-up.

English society c. 1600

England by 1603 was a society facing considerable strain. Despite the fact that the previous century had witnessed a dramatic population rise, from around 2.8 million to over 5 million inhabitants between the 1520s and 1640s, there had been little change in the pattern of life for most people. Ninety per cent of the population still lived in rural areas and were dependent on agriculture for their means of existence. Although London was the largest city in the country, with a population of around 200,000 by 1600, there were only two other cities with more than 10,000 inhabitants, Norwich and Bristol. Five others had populations of over 5,000, namely Oxford, Salisbury, York, Newcastle and Exeter.

In particular, there was a sense of the threat posed by landless vagrants, victims of economic change, whose lifestyle meant that they were beyond the traditional control mechanisms of society. As one magistrate from Somerset warned in 1596:

In response to this threat, a series of Poor Laws was introduced. These included a range of measures designed to alleviate poverty and to punish those who sought to escape it by moving out of their home areas. William Harrison, in 1587, described graphically how such legislation was to work:

Government

Role of monarch

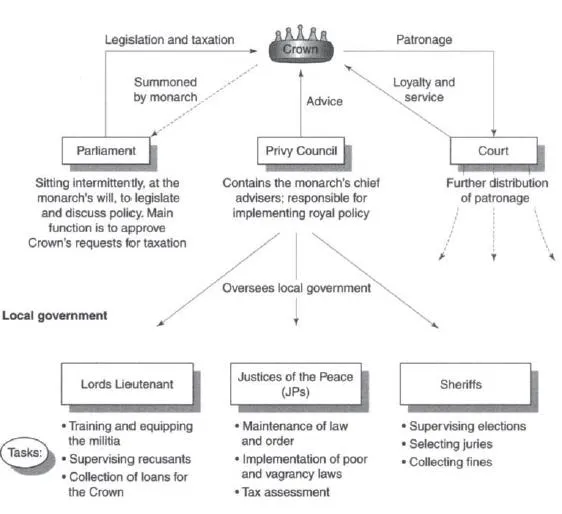

As Head of State and Church, the powers and responsibilities James inherited as King of England were enormous. Government revolved around the monarch and was its Government. As Defender of the Faith, the monarch appointed archbishops and bishops, and directed ecclesiastical policy. Judges and magistrates were appointed by the Crown to uphold its laws. The monarch directed foreign and domestic policy, chose its ministers, raised and controlled armies, and decided if and when to call the peoples representatives together in Parliament. Parliaments were usually summoned to provide the Crown with financial assistance, but the ultimate responsibility for finance also belonged to the monarch. Any financial difficulties would lead to a Crown debt rather than a national one, for which the monarch was responsible.

How Government worked

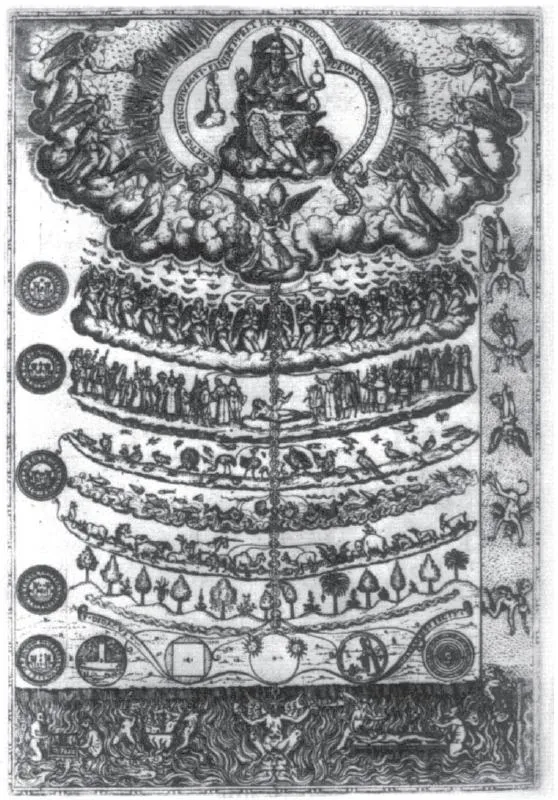

Lacking a standing army, an effective police force or a professional civil service in the localities, the Government was heavily dependent on persuasion to enforce its will. As we have seen, the idea of a Great Chain of Being was an important one at this time, and one that Government propaganda developed.‘The homily of obedience’ emphasised the monarch’s divinely appointed right to issue orders that their subjects must obey. Failure to do so would lead to anarchy: ‘no man shall ride or go on the highway unrobbed; no man shall sleep in his own house or bed unkilled; no man shall keep his wife, children, and possessions’.

The machinery of Government

The actual machinery of Government at the disposal of the monarch was relatively limited. At a central level, the most important institution was the Privy Council, which provided the monarch with advice and implemented royal policy. Great officeholders, such as the Lord Treasurer, or Secretary of State, would usually sit on the Privy Council, and were influential figures in Court as well.The Court, although not part of the Government machine as such, was also an important source of advice to the monarch, and the main channel through which patronage was distributed. A number of central courts also sat in London, which dealt, among other things, with the enforcement of the monarch’s rights and the settlement of constitutional issues. When summoned, Parliament could pass legislation and provide access to important tax revenues.

Government by 1603

While Elizabethan government was remarkably successful given the constraints under which it was operating, there were certain issues evident by 1603. One was the importance of ensuring a wide distribution of patronage, and avoiding a monopoly over it, or Government, by any one individual or group. According to one contemporary, Elizabeth ‘ruled much by faction and parties which herself both made, upheld, and weakened, as her own judgment advised’. The tensions that accompanied the rise of the Earl of Essex, and his domination of the elderly Queen’s favours towards the end of the reign, clearly illustrated the problems that could arise if this was not the case.

Finance

Responsibility for finance also lay with the Crown, and sound finances were therefore vital to its ability to provide effective government. In theory, monarchs were expected to meet the normal costs of maintaining their Court and government through their ordinary revenues. These were split into four categor ies. Traditionally the most important source was the rents from Crown lands, although customs duties including levies such as tonnage and poundage, were also significant. These sources were supplemented from the profits of justice, the Crown benefiting from fines and confiscations of land, and from feudal dues. The latter consisted of a ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. The Stuart Inheritance

- 2. James I, 1603–25

- 3. Charles I, 1625–9

- 4. The Personal Rule of Charles I, 1629–40

- 5. Political Conflict, 1640–2

- 6. Civil War, 1642–6

- 7. The Search for a Settlement, 1646–9

- 8. The European Context

- 9. The Republic, 1649–60

- 10. Charles II, 1660–73

- 11. Charles II, 1673–85

- 12. James II, 1685–8

- 13. Glorious Revolution?, 1688–1701

- Conclusion

- Appendix: Notes On Authors of Documents

- Glossary

- Guide to Further Reading

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app