- 300 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Human Resource Management

About this book

The majority of textbooks on HRM tend to focus on the administrative side of the subject and fail to examine its strategic importance. This book is intended to redress the balance and, taking strategy as its starting point, it looks at the overall role

of HRM in the organization.

The author explores strategic human resource management through chapters on managing change in strategy, structure, and culture; the role of human resource planning, and types of employment system. He also reviews some of the key issues in managing different employee groups. These themes are problem- and issue- focused and extensively illustrated throughout with case study examples. Dr Chris Hendry is the author of many reports, research papers and articles on HRM and strategic management.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One

The Making of Human Resource Management

1

Human resource management: an overview

Introduction

Human resource management (HRM) has gained rapid and widespread acceptance as a new term for managing employment. It remains, however, an ambiguous concept. People question whether it is any different from traditional personnel management, nor is it altogether clear what it consists of in practice.

This chapter sets out the background of ideas on which HRM is based. Three common interpretations are identified. HRM is then compared with personnel management, identifying the special shortcomings of personnel management and those it shares with HRM.

The chapter concludes by setting out the approach adopted in this book. This combines a view of organizations as employment systems set against the requirement to manage organizations in accordance with current business strategy.

What do we mean by HRM?

Our starting point is that HRM has different connotations for different people and does not yet constitute a unified theory. We are all familiar with such statements as ‘our human resources are our most important asset’. In some cases, acceptance of the principles of HRM goes no further than this. Others emphasize that it is about matching employment practices to an organization's strategy. A corollary of this is that, taken as a whole, employment practices should combine together to reinforce one another. Part of this is that employment decisions should not be conceived in isolation, but ideally should be integrated through mechanisms such as personnel planning. At the same time, reward systems, the way promotions are made, who gets trained and why, all have effects on motivation and say something about what kind of organization it is and what behaviours it wants to promote. HRM is about making sure such personnel practices convey a consistent message.

A third connotation is to present HRM as having a distinctive philosophy underpinning it, not just any set of values. This philosophy emphasizes securing employee commitment and motivation in organizations characterized by high-trust relations, with scope for employees to exercise influence. Management style and organizational culture then become an important focus for action in their own right. It is not enough that employment practices cohere, nor even that they should express the values of the organization. These values are of a particular kind.

These are the three common expressions of HRM. However, they cannot simply be added together to produce a complete theory or prescription. While the first proposition sits comfortably with the last, it is very easy, for example, to conceive of employment practices conditioned by a business strategy that depends on producing at lowest cost in an unstable product environment. Such a business might rely on low pay, part-time working, and hire-and-fire arrangements which enable it to respond rapidly to fluctuations in orders – in other words, to use casualization as an employment strategy. Dock work once used to be like this, as the movement of cargo vessels changed by the day. If, on the other hand, employees have craft skills and/or high levels of effort are required in a concentrated period, casualization may be accompanied by high levels of pay – as in the construction industry. By this yardstick construction firms could be said to practise a kind of ‘HRM’.

When someone talks therefore about ‘creating excellence through a culture of commitment’ and ‘managing cultures to create excellence’, while arguing also for personnel policies being linked with corporate objectives and strategic plans, we should beware. Such rhetoric obscures potentially incompatible definitions and ignores the reality of employment systems. Let us look a little more closely, therefore, at what is contained in these definitions and begin to sketch some of the potential weaknesses in the principles themselves.

Human resources are our most important asset

The idea of people as a valuable organizational asset has a sound pedigree in the economists’ theory of human capital. It means something specific that is, in principle, measurable. So, for example, human capital can be enhanced by the further investment of education and training, just as the physical capital of a factory can be by modernization. Equally, both can deteriorate through ageing, obsolescence, and neglect.

In its more general use in the management literature, where it has been more or less explicit since Peter Drucker (1954), this idea tends to get watered down into ‘motherhood statements’ about people being important to the functioning of an organization. A number of academic writers have nevertheless been influenced by ‘human capital’ theory and have developed principles for action around it. Douglas McGregor (1960) (an educationalist-turned-management consultant), in his ‘Theory X-Theory Y’, argued that the way managers treat employees will affect how much of their talent, effort, and motivation can be harnessed for the organization. In other words, how much of the human capital can be tapped.

This opened the way for the behavioural science school (represented by people such as Herzberg) to incorporate psychological theories of personal growth, particularly that of Maslow (1943), into their theories of organization. The underlying belief, which ‘organization development’ (OD) consultants turned into a programme of action in the 1960s/1970s, was made explicit in Argyris's (1964) book, Integrating the Individual and the Organization, where personal growth was represented as entirely compatible with an organization's objectives. In due course, human resource management has picked up this convenient assumption.

Over the years this has attracted much criticism, since it plays down, for example, the imbalance in power between the mass of individuals and that exercised by the few in the name of the organization. The problem comes back to the idea of people as ‘assets’ and ‘resources’ which John Morris (1974) tellingly exposed in his pointed distinction between ‘human resources’ and ‘resourceful humans’. Human resources are the readily manipulated footsoldiers of organizations; resourceful humans are the managers and others, but particularly managers, who initiate. The best test of resourcefulness, then, is to go out and start one's own business.

We need not accept this conflict in quite such a stark way. It is clear organizations, by definition, ‘organize’ people and that the majority of people work within organizations. The recently popularized idea of ‘intrapreneurship’ (Kanter, 1984) suggests the importance of giving space to resourceful, entrepreneurial individuals within the organization, and ways of doing this. ‘Intrapreneurship’ depends precisely on opening up a gap between the pressures of organization and the individual, not on ‘integration’.

Thus, writers like Kanter are concerned with how to mobilize people's talents to advantage the organization, but do not take on board an overt set of values about personal growth, nor other explicit elements of a theory of HRM. The issue of integration has resurfaced in criticisms of HRM, nevertheless, and we will consider these later.

Looked at historically, then, the early adoption of the title, ‘human resource(s) manager/director’, in a handful of American companies during the 1970s, before any theory of HRM had been elaborated, was probably nothing more than a statement about the importance of people to an organization (Janger, 1977). By the mid-1980s in the USA, and in the UK by the late 1980s, the more widespread use of such titles harboured larger ambitions.

Matching employment practices to business strategy

The first major theoretical advance came in the classic statement of HRM by Fombrun, Tichy and Devanna (1984). Building on Alfred Chandler's (1962) argument that structure should follow strategy or an organization will be otherwise less efficient, two theorists of business strategy, Galbraith and Nathanson (1978), extended this to argue that HRM systems should similarly be adapted to match the requirements of strategy. Fombrun, Tichy and Devanna (1984) then fleshed this out, adding various elements of personnel policy:

Just as firms will be faced with inefficiencies when they try to implement new strategies with outmoded structures, so they will also face problems of implementation when they attempt to effect new strategies with inappropriate HR systems. The critical managerial task is to align the formal structure and the HR systems so that they drive the strategic objectives of the organization (p. 37).

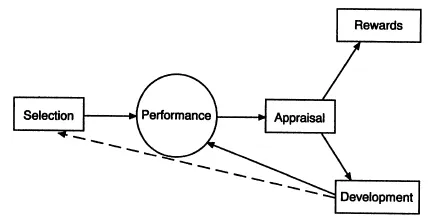

The key human resource (HR) systems for them were selection, appraisal, development (including training), and rewards. These had the potential to channel behaviour towards specific performance goals, if they were properly aligned with one another – as their model of the human resource cycle suggests (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The human resource cycle. (Source: Fombrun, Tichy and Devanna, 1984)

In a further elaboration, they introduced the idea of organizational culture, or what they termed the ‘dominant value’. HR practices implicitly or explicitly create characteristic organizational cultures, and reinforce one another insofar as they support a particular culture. As a result, ‘culture’ becomes the crucial intervening variable.

There is one significant omission from their model, however, which will be all the more evident when we look at the contribution of the Harvard school to the theory of HRM. They omit industrial relations, or employee relations, as a major focus of managerial activity. Fombrun, Tichy and Devanna (1984) are principally concerned with the ‘new labour force’ (p. 8) of managers, professionals, and white-collar workers – the changing occupational balance in favour of whom is one of the important contextual factors that makes HRM desirable. The focus is on selection, appraisal, development, and rewards almost exclusively in relation to staff.

This omission is symptomatic and can be linked to other elements of their thinking. Compared with the Harvard school, there is little sense that choices might be contested or need to be negotiated. Although they imply culture involves a choice, it is implicitly determined by whatever direction business strategy is taking. Managers are not challenged to reassess their personal values and those the organization embodies – either by other employees or by the authors themselves. Indeed, sometimes there is a feeling that choices are made and decisions taken without human intervention.

For Fombrun, Tichy and Devanna business strategy precedes any other considerations, and HR systems are contingent upon strategic need. Although other contributors to their edited volume develop particular aspects of HR systems with varying degrees of attention to the nature of managerial choice and employee influences on this, they are generally all wedded to this contingency model. They and their imitators are thus active in devising frameworks that link different strategic circumstances to sets of HR practices. We shall look at these in more detail in Chapter 4.

Before turning to the Harvard school, it is worth keeping in mind that although managers de facto make choices daily to do with people, they may not consciously reflect on these. The needs of the business may well be uppermost in their minds, and implicitly they may reaffirm a set of values moulded around ‘strategic imperatives’. Rarely do people review their fundamental assumptions about behaviour. There is a realism here, therefore, unintended though it is, about the extent to which managers can and do make conscious HR choices.

In a way, however, this backfires also on the idea that managers make deliberate choices about business strategy. As we shall argue in Chapter 4, making strategy and therefore determining the direction of an organization is rather more complex than these writers credit. HR theorists have in common a belief in managers being able to make deliberate choices, yet the whole question of managerial choice, in business strategy and employment systems, is far from straightforward.

HRM as a philosophy of management

If Fombrun and his colleagues represent one of the two schools of contemporary HRM in North America, Michael Beer and his colleagues at Harvard are the foremost proponents of the other. Their ideas are contained in two key books (Beer et al, 1984; Walton and Lawrence, 1985), which were written to provide the conceptual underpinning for the new Harvard core course in HRM launched in 1981 – the first such innovation to the core programme, as they point out, in twenty years.

Where others draw on the strategy literature, the source of inspiration for the Harvard group lay within the human relations/human resources movement. A number, such as Paul Lawrence and Richard Walton, for example, had been prominent as consultants and writers in OD – although the fault lines running through OD meant that Michael Beer (1976) had been a notable critic, and Lawrence (1969) had co-authored a seminal text from a structural contingency perspective. These complications of history and intellectual development aside, in their representation of HRM they put more stress on people as ‘human resources’, with their needs and potential for personal development, whereas Fombrun, Tichy and Devanna appear to give greater emphasis to HR systems.

Thus, people are at the centre of the Harvard model, with management taking decisions affecting people day in, day out:

Human resource management involves all management decisions that affect the nature of the relationship between the organization and its employees – its human resources. General management make important decisions daily that affect this relationship (Beer et al, 1984, p. 1).

They explicitly reject the idea that employment systems should be simply responsive to technical, social and economic factors, although they acknowledge that ‘most firms’ employment policies are less reflective of a coherent set of management attitudes and values than ... of the economic environment in which that organization operates’ (Beer et al, 1984, p. 101).

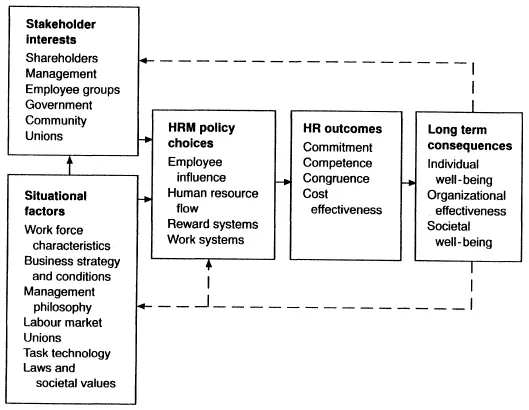

Instead, managers can and should make choices about the organizations they want to create; these choices respond to a wide range of factors; and certain choices are preferable from a moral (and, in their eyes, a practical) point of view. Thus, their model (shown in Figure 1.2) is much more inclusive, business strategy, for example, being but one among a number of situational factors (or contingencies). Employee influence is a key area of decision (or ‘choice’), and is affected by a number of other stakeholder interests than just management. By the same token, HRM practices have consequences not just for company performance but for the individual and society.

Figure 1.2 Map of the HRM territory. (Source: Beer et al., 1984)

The touchstone for HRM practices is not therefore simply whether they provide an efficient ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Series

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Part I The Making of Human Resource Management

- 1 Human resource management: an overview

- 2 The context for HRM

- 3 HRM in practice

- Part II Strategy, Structure, and Culture in Organizational Change and HRM

- 4 Business strategy and organizational capability

- 5 Organization structure and human resource management

- 6 Corporate culture and the management of organizational change

- 7 Strategic change and HRM at Barclaycard: from rapid growth to maturity

- 8 Strategy, structure and cultural change: managing retrenchment and recovery at PilKington

- Part III Basic Concepts for an Employment Systems Perspective

- 9 Manpower planning

- 10 From manpower planning to human resource planning

- 11 Employment systems: recruitment, pay, and careers

- 12 Managing the system as a whole: towards HRM (1)

- 13 Managing the system as a whole: towards HRM (2)

- Part IV Employee Groups

- 14 Managers and professional employees

- 15 Managers in an international context

- 16 Manual and clerical employees

- 17 Managing technical and organizational change at GKN Hardy Spicer

- 18 Flexible employees: flexible firms

- 19 Skills and training in the European Union and beyond

- Part V Conclusion

- Future scenarios: issues for the 1990s and beyond

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Human Resource Management by Chris Hendry in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.