- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Architects Without Frontiers

About this book

From the targeted demolition of Mostar's Stari-Most Bridge in 1993 to the physical and social havoc caused by the 2004 Boxing Day Tsunami, the history of cities is often a history of destruction and reconstruction. But what political and aesthetic criteria should guide us in the rebuilding of cities devastated by war and natural calamities?

The title of this timely and inspiring new book, Architects Without Frontiers, points to the potential for architects to play important roles in post-war relief and reconstruction. By working "sans frontières", Charlesworth suggests that architects and design professionals have a significant opportunity to assist peace-making and reconstruction efforts in the period immediately after conflict or disaster, when much of the housing, hospital, educational, transport, civic and business infrastructure has been destroyed or badly damaged.

Through selected case studies, Charlesworth examines the role of architects, planners, urban designers and landscape architects in three cities following conflict - Beirut, Nicosia and Mostar - three cities where the mental and physical scars of violent conflict still remain. This book expands the traditional role of the architect from 'hero' to 'peacemaker' and discusses how design educators can stretch their wings to encompass the proliferating agendas and sites of civil unrest.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

From lines of contention to Zones of connection

Healing wounds and building peace is not the exclusive responsibility of politicians. We, as architects and urban and regional planners, have a major role to play – and a matching responsibility.

(Barakat, 1998: 15)

This book traces my journey as a nomadic architect living and working in cities destroyed by war and ethnic conflict. My specific concern in this investigation is with the role of architects as potential peace-builders in the rebuilding of such cities. The case studies of reconstruction that form the central part of this book chronicle my search for social resonance in the design field, specifically to uncover the roles that architects can play across the broad terrain of post-disaster reconstruction.

Since I began my research on a range of cities destroyed by civil conflict more than a decade ago, the issues of war, terrorism, trauma, amnesia, memory and reconstruction have grown exponentially in the public consciousness. This comes about largely as a result of a tragic global increase in post-Cold War, intra-ethnic and religious warfare and the related catastrophic outbursts of targeted urban conflict and violence. These conflicts include (but are not limited to) the bombing of Belgrade in 1999, the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on 11 September 2001, the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan in March 2001, the destruction of Kabul later that year and, in 2005, the demolition of urban and industrial infrastructure in Baghdad.

While some progress is being made in isolated ethnic conflicts, such as the imminent removal of the Green Line barrier across the island of Cyprus and its capital city, Nicosia, newer, larger and even more aggressive barriers are being erected (and in some cases, such as Jerusalem, re-erected) to partition cities in other parts of the world from Lagos to Ahmedabad. The possibility of urban warfare has also become a daily threat through the over-dramatized reporting of ‘global terrorism’. Somma comments:

War no longer is something abnormal. The subject of war and the city and the various combinations possible between the two terms, war against the city, the city at war with the rest, the city at war with itself, risk becoming mere academic disciplines and fields of speculation.

(Somma, 2002: 1)

Two related sets of decisions face professionals working in the field of post-war reconstruction. The first rests in the political process of forming new structures of governance in the reconstitution of a ‘civil society’; the second decision rests in the type of reconstruction to be followed, that is, will a city be rebuilt along a traditional or a modern style? The first decision relates to whether efforts will be made to integrate the former warring groups under one or several territorial umbrellas, or whether residential segregation will be maintained. This decision is essentially political, but it has critical social implications, and implications for the nature of the planning and design processes to be adopted, the focus of this book.

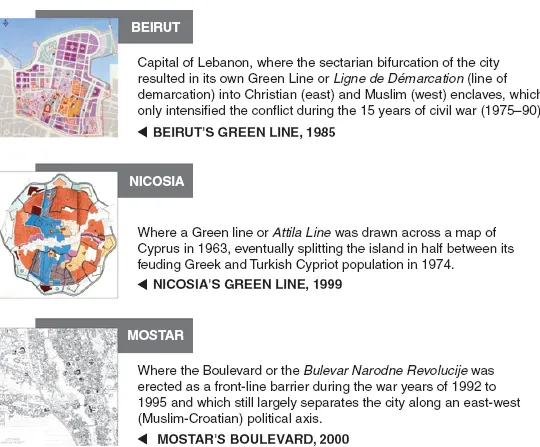

In the following chapters I examine three case studies: the post-war cities of Beirut, Nicosia and Mostar, and the attempts by urban planners and architects in these cities to reconstruct the urban fabric after the conflicts ended (figure 1.1). My emphasis is upon the socio-spatial effects of war, rather than a detailed analysis of the historical causes of conflict. My aim is not to provide a template for reconstruction: this would be naive and misguided, given the cultural and political peculiarities of each city under examination, and, indeed, of all cities. This investigation is, instead, used to propose a flexible framework to allow architects and other design professionals, such as planners, urban designers and landscape architects (all of whom are referred to here under the collective name of ‘architects’), to engage in the processes of social, economic and physical reconstruction. My findings target design professionals wishing to be involved (or who are already involved) in the post-conflict field and/or already engaged in international development projects. They are also of great relevance for design educators, for it is in our universities that the seeds of professional ethics and responsibility need to be sown.

Three case studies

Figure 1.1

THREE POST-WAR RECONSTRUCTION CASE STUDIES

The title of this chapter, ‘From lines of contention to zones of connection’, provides a context in which architects can assist peace-making efforts in the period immediately after conflict, when partition lines demarcate the boundaries of each warring territory and each party tries to consolidate its shift into its (former) enemy’s space. Once an initial political consensus is reached (and there is rarely any point in talking about connection before at least minimal consensus is reached) then the buffer zone along the partition lines becomes the area or zone with most potential for connections. A practical example of such a zone of connection is Rue Monot in East Beirut, which was aligned to the Green Line during the Lebanese civil war, but today is the most popular zone for night entertainment in the country for Muslims and Christians alike.

The main criteria for my selection of the case studies of Beirut, Nicosia and Mostar are, firstly, that all three cities have been divided by a physical partition line; secondly, that all these conflicts have been inter-ethnic in nature; thirdly, that all these conflicts are still unresolved and, finally, that the roles played (or not played) by architects in reconstruction provide a basis from which more general lessons may be derived.

The three case studies (Figure 1.1) also represent different ways that war can divide and destroy a city, historically and physically, as well as a range of design approaches to dealing with the post-war debris. They include:

• Beirut, capital of Lebanon, where the sectarian bifurcation of the city resulted in its own Green Line or Ligne de Démarcation (line of demarcation) into Christian (east) and Muslim (west) enclaves, which only intensified the conflict during the fifteen years of civil war (1975–90),

• Nicosia, where a Green Line or Attila Line was drawn across a map of Cyprus in 1963, eventually splitting the island in half between its feuding Greek and Turkish Cypriot population in 1974 and

• Mostar, where the Boulevard or the Bulevar Narodne Revolucije was erected as a frontline barrier during the war years of 1992 to 1995 and which still largely separates the city along an east–west (Muslim–Croatian) political axis.

While the dividing lines and barriers may have been removed – at least officially – as strategic checkpoints or formal walls in Beirut and Mostar, the book considers why the ethos of partition often remains in the mental maps of residents as psychological fractures and political barriers that loom even greater than they were during the original periods of conflict. For example, a West Beirut (predominantly Muslim area) resident living on the edge of the city’s Green Line commented:

Do you want me to tell the truth? I don’t consider the war over. As long as there are forces outside the Lebanese government, there is going to be a demarcation line. My perception of the situation, being an educated woman, is that the war is not over. The shelling has stopped but the war isn’t over. The mentalities are still at war.1

Unfortunately, the reconstruction strategies under investigation in the three case studies include few architectural or urban planning schemes designed to promote the social reconnection of these ethnically partitioned cities. One positive example that will be discussed, however, is the Nicosia master plan project that proposed reconnecting the city by reconstructing the buffer zone and establishing bi-communal communication between the Greek and Turkish Cypriot residents on the island. Ironically, however, the reconstruction plans of Beirut and Mostar have often undermined the goal of long-term peace. For example, the Solidere reconstruction project in Beirut explicitly excluded the Green Line area of the city from its boundaries, even though this former front line of war is right on the edge of the developable land in the reconstruction project.

The patterns of social and economic polarization manifested in physical separation in the politically contested cities of Mostar, Beirut and Nicosia provide a potential future trajectory for many North American and European cities, as will be outlined in subsequent chapters. These post-war environments of sectarian and racial turmoil, pushed right to the fault line of physical partition, can provide profound insights into the fear, separation, violence and alienation that run through most large metropolises. War-damaged cities also force us to explore urban antagonism and tolerance, and to see how designers, planners and policy-makers can contribute practically to the alleviation of racial and social segregation.

Post-war odyssey

My exposure to the infinite dilemmas of post-disaster reconstruction began as a result of a trip I made as one of eighteen postgraduate students at Harvard who took part in a design workshop sponsored by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture in 1994. The workshop, held in Istanbul, focused on the reconstruction of Mostar, a small Ottoman town in Bosnia destroyed by the civil war in the former Yugoslavia. I arrived at the workshop that summer knowing little about Bosnia, the war and how, or even if, architects could be useful in the social reconstruction process after the catastrophe of civil war. Ironically, while we were making seductive drawings of glass and steel structures to replace the fallen Stari Most Bridge, the city was going without water, sanitation and adequate housing for the thousands of refugees then flooding into Mostar. I found one example during my fieldwork in 2000 particularly disconcerting. In Mostar millions of dollars were allocated to the reconstruction of the Stari Most Bridge while the Neretva River flowing beneath contained untreated sewage and hospital waste, making it a public health hazard for the city’s residents. In that same year, it was hard to ignore the fact that only 2 kilometres outside the city of Mostar a growing number of war refugees were living in steel container crates.

In time we came to a less naive understanding by listening to personal narratives of war and studying photographs and films of the ruins wrought by conflict in the city. Our growing realization of the stark reality of the violence and destruction of war contrasted sharply with our highly romantic design attempts to reconfigure the city. This experience in Mostar ultimately set me on an investigative path to find more effective models for post-war reconstruction and to understand how architecture can contribute to the social reconstruction of divided societies through the physical reconstruction of urban landscapes and infrastructure.

Subsequent research and project visits to other war-damaged cities suggested to me that many architects working in the field of post-war reconstruction limit their professional roles to reacting to the physical symptoms of destruction without attempting to understand the root causes behind the conflict. ‘Symptoms’ here are defined as the immediate damage inflicted on cities during periods of sustained conflict, such as damage to the physical infrastructure of their services, utilities and buildings as well as the destruction of iconic or historic structures such as their bridges and religious monuments.

Now, in 2006, more than a decade after my introduction to the destroyed city of Mostar, I continue to reflect on the responsibilities and rights of architects, in both theory and practice, to intervene through design projects within, or on behalf of, communities tragically affected by violence, segregation, urban dysfunction and partition. For example, I have asked myself whether architects should adopt an interventionist stance by taking a professional stand against the violation of human rights and legal injustices caused by civil conflict, and by seeking to use their design expertise to minimize the chances of future conflict? Or is it more ethical to await official commissions for projects to repair the urban fabric destroyed by war? Increasingly, I have come to see the latter as an unprofessional option. However, it is a very common view and was forcefully expressed in a statement from a group of planners and architects I interviewed in Belfast. When I asked about the role of design professionals in the social reconciliation of their still highly fractured city, one senior academic remarked: ‘What does planning have to do with alleviating sectarian conflict?’2

During my explorations in Beirut, Mostar and Nicosia, I similarly became disillusioned with the activities of many foreign architects invited to work as experts in the postwar field. Generally, they had little experience of working in divided political and physical landscapes and, as a result, tended to produce (and impose) quick-fix design strategies that are attractive to international donors but which invariably denied or, in some cases, accelerated the underlying causes of conflict. It became increasingly disconcerting to observe what might be called the foreign architect’s fetish for rebuilding ‘cultural heritage icons’. Such an obsession is displayed by local and foreign designers who assume that the immediate reconstruction of the historic core of a war-devastated city (or a historic bridge, such as the Stari Most Bridge in Mostar or Martyrs’ Square in Beirut) will restore the city, almost immediately, to its prewar identity and community spirit. Such stances often ignore the fact that the surrounding urban tissue, infrastructure and social fabric are lying in chaos all around them. These architects – and their commercial, political or international patrons – rarely focused on the ‘leftover’ zones, especially the dividing lines of conflict or the often abandoned and neglected peripheries of the central zones of cities such as Beirut, Mostar and Nicosia.

Related to this deficiency of social and physical analysis in the post-war design field, many design projects in Mostar have concentrated on culturally significant structures, such as the rebuilding of mosques in the old city (Stari-Grad). Similarly, in Beirut, Solidere, the private development company rebuilding the Beirut central district, used ‘cultural heritage’ arguments to validate its selective reconstruction of Roman archaeological sites in the city’s former downtown. This effectively distracted attention from the same company’s demolition of much of Beirut’s historic centre. The p...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- 1 From lines of contention to zones of connection

- 2 Architects and war

- 3 Archetypes

- 4 Beirut – city as heart versus city as spine

- 5 Nicosia – reconstruction as resolution

- 6 Mostar – reconstruction as reconciliation

- 7 From zones of contention to lines of connection – implications for the design profession

- 8 Architects without frontiers – implications for design education

- Bibliography

- Further Reading

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Architects Without Frontiers by Esther Charlesworth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architektur & Architektur Allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.