![]()

Part 1

The global dilemma

![]()

1 | The dilemma of mobility |

| Nicholas Low and Kevin O’Connor |

Introduction

Transforming Urban Transport confronts head on the dilemma faced by a world wedded to mobility: the danger of continuing along the fossil-fuelled transport path and the real difficulty of replacing private vehicle solutions in time to avoid dangerous climate change. There are major barriers to change and it takes time and strategy to overcome them. But there are also solutions and ways forward, some of which we explore in the chapters to follow. It is the purpose of this chapter to sketch out the argument of the book. Many of the ideas are not new, but the way we present the problem and bring together strategies to overcome it represents a new perspective and reveals more about the necessary social and institutional change than has hitherto been attempted.

In earlier work (Low and Gleeson, 2003: 17; Low, 2002) we have argued that transforming transport will occur through a process of ‘ecosocialization’ following Karl Polanyi’s ‘Great Transformation’ in which the social contradictions of capitalism were partially resolved through a movement of social protection that culminated in welfare states (Polanyi, 1957). In the same way a movement of environmental protection is attempting to resolve the environmental contradictions of capitalism. There is evidence from around the world that this is happening. But will it move fast enough? In truth the task of transforming transport on a global scale is vast. We see the same cities cited again and again as evidence of change, and as models of good practice – for example, Portland, Vancouver, Curitiba, Zürich, Freiburg, Copenhagen, and sometimes Seoul and Singapore – yet none of the transport systems even of these cities can measure up to a rigorous analysis as ‘sustainable’. And the vast bulk of cities and new urban development worldwide remain determined by the paradigm of automobility. Even the impoverished nation of Pakistan is building roads and flyovers to accommodate the tiny minority of aspiring motorists (Imran, 2010). The dilemma is so profound and the roots of unsustainable transport run so deep that both urgency and a degree of pessimism are warranted if we are to view the problem of change in its true light.

The rise and fall of automobility

We characterize the vision driving transport policy during most of the twentieth century – and still persisting – as automobility, a conception of transport that came to infuse thinking about cities and their future worldwide. In the latter part of the twentieth century, city building proceeded on the assumption that the spatial relationships among the various activities going on in urban regions were best left to the individual choices of persons and firms under the discipline of a land market. The need to move between activities, for so long organized by collective transport systems, could now be met by individual mobility.

The form of transport that most perfectly matched the individualistic ideal of the free market was the private motor vehicle. Private cars greatly increased the choice of where to live and work, and freed labour from the tyranny of proximity to workplaces. As a mode of travel the car combined speed, flexibility and control over personal space (Pooley et al., 2006). For firms, private trucks could deliver goods ‘just in time’ to meet demand wherever, whenever they were wanted, unlimited by timetabled services at railheads or ports. In this way the crude rigidities of collective transport could be avoided. In real terms too, this form of mobility became cheaper as the cost of cars and trucks, and the cost of fuel, fell steadily – despite oil price spikes in the 1970s. The consequent flexibility of movement provided a flexibility of locational choice for firms and individuals in tune with the flexibility of markets for goods and services.

A knowledge industry employing hundreds of thousands of consultants and scholars was built around making and justifying the infrastructure needed to allow the ideal of ‘free movement’ to be pursued. Engineers not only perfected efficient road design but also developed the traffic, land use and travel behaviour models that would come to define the problem to which engineering mega-projects were the solution. The ‘project sublime’, able to slice through mountains, lightly span great distances, keep traffic flowing and tunnel between the pipes and foundations under cities impressed politicians and the public. All transport problems, it seemed, would yield to engineering solutions – while defining the problems in the terms that engineering would solve.

But these compelling ideals turned out to be a mirage. Although it seemed that transport relied upon individual choice, cars and trucks run on publicly constructed roads. Pure market principles were violated in the spatial unevenness created by the selective network effects of the location of the highest quality roads and railways. Rights to travel entail ‘specific often highly embedded and immobile infrastructures’ (Sheller and Urry, 2006: 210). Collective transport continued in use, filling the gaps where individual transport failed. Traffic congestion increased. Urban environments filled with vehicle fumes and noise, and in some places vast areas of parking lots took over the public space. Land use planning controls limited the locations of some activities in most cities. Road traffic caused deaths and injuries worldwide on a scale greater even than the scourge of malaria. Finally, individual transport was only ‘cheap’ when its external impacts were ignored. So the market-technical ideal was never really approachable. Today, with the looming fact of global warming and the need to stop burning fossil fuel, and with the rapid depletion of oil – the source of cheap transport – the mirage has dissipated further so that individual motorized mobility will need to be re-thought as a means of connecting activities in urban regions in the twenty first century.

The tension within cities between the ideal and the reality is replicated at the global scale. The neo-liberal governance of the global economy requires that the location of productive activities be determined by flexible supply and demand forces in the global market. Mobility provides a way to take advantage of these forces. So production now involves global supply chains connecting the activity of large and small firms often over vast inter-continental distances. Cheap mobility has solved the problem of distance, not only between producers and consumers but also between different producers and among the production facilities within corporations. The health and efficiency of the global economy, it can reasonably be said, now hinges on the cheap mobility of goods. Here too global warming and oil depletion will force the global economy to face an uncertain future. And insofar as the global economy is an economy of cities, the problems of global mobility intersect with those of urban mobility.

The idea of sustainable transport

As the ideal of automobility entered its long decline, a new ideal model started to take shape characterized as sustainable transport. Instead of starting from the premise that perfect mobility was possible and desirable within safe speed limits made available by current vehicle technology, sustainable transport starts from the premise of reducing the social and environmental damage caused by motorized mobility. This understanding recognizes that oil production will peak and decline, costs of fuel will rise, and that there will be growing demand for better public transport of people and goods. However there remain serious conceptual problems, and problems of measurement of ‘sustainability’. The new paradigm of sustainable transport and its governance – both global and local – are discussed in Chapter 4.

Dissatisfaction with automobility, or ‘hypermobility’ (Adams, 1999, 2000) stemmed from the actual loss of quality of urban environments and worries about urban sprawl, the destructive effects on rural environments caused by road building, the discovery and confirmation of ‘induced traffic’ (SACTRA, 1994, 1999; Goodwin, 1996), fears for the consequences of comprehensive plans for cities served by networks of motorways (Sachs, 1992; Davison with Yelland, 2004). In later years, to these fears were added the global problems of climate change and peak oil – the tendency of world oil production to reach a peak and then decline (Campbell, 2003; Betsil and Bulkeley, 2007; Chapman, 2007; Aleklett et al., 2010).

In an attempt to define alternatives to automobility much has been written about the idea and practices of sustainable transport (Whitelegg, 1997; Newman and Kenworthy, 1999; Low and Gleeson, 2003; Schäfer et al., 2009; Schiller, Bruun and Kenworthy, 2010). The OECD and even the car companies themselves have adopted the concept of sustainable travel or sustainable mobility (OECD, 1995; WBCSD, 2004). Plainly ‘sustainability’ embraces a multitude of conflicting interests. However, there are three aspects of the problematic on which all analysts seem to agree: the global scope of the problem, the deeply entrenched character of automobility and the need to change. It is the question of institutional change in varied contexts but of global scope that is the main theme of this book. Given the acknowledged urgency of the need for the transport sector to change, how is this to be achieved? Indeed, can it be achieved in time to avoid the most dangerous consequences of global warming?

The book addresses this question via an analysis of three themes: the global dilemma of mobility, the institutional dimensions of change, and local strategies to induce change.

The dilemma of mobility (Chapters 2 and 3)

This theme poses the dilemma shaped by practices of mobility deeply entrenched in societies and cultures worldwide, now juxtaposed with an acknowledgement of the need for massive and rapid cuts to emissions from the fuels that have driven this mobility. Understanding the dilemma, we argue, is the first step towards changing the assumptions and developing strategies.

The institutional dimensions of change (Chapters 4 to 6)

The dilemma outlined above is expressed in the institutional and cultural structures that have facilitated and enhanced the current mobilities. Hence change will only occur once the assumptions embedded in these structures are identified and understood, and the structures themselves change. Their political, social and economic persistence – the common norm – acts as a barrier to change in most societies.

Strategies for local change (Chapters 7 to 11)

Strategies for change will be multiple and variable. Strategies must start from today’s realities. To illustrate that, a selection of practical strategies is discussed. These include the governance of transport planning in dispersed and concentrated cities, the analytical techniques aimed at indicating transport need, the policies to induce change in mobility for the child, the political mobilization needed to promote change, and the way new knowledge may be mutually discussed and shared.

Shifting the world to put sustainable transport into practice and replace the dominant global model of automobility requires us to go beyond stating and restating the principles of sustainable transport and giving good examples of practice – and in a global context they are in reality all too few. If we are to change our habits of mobility in the interests of stabilizing the global climate and coping with reduced oil supply we should be clear about the basis of those habits, and find ways to help them change.

The significance of mobility

Geographers and economists have long recognized the ‘collapse of spatial barriers’ over time and the important role of the private vehicle – passenger and goods – in shaping the development of cities in the twentieth century. The significance of that role was captured by Clark (1996: 100) when he observed that, ‘the ability to participate in an urban way of life is largely independent of location and is open to all’. There is nothing new about this outcome. Personal mobility has been growing steadily in the developed world for centuries, and that is being reprised in the emerging economies in step with the development of technology and the broadly based economic development associated with industrialization. Pointing out the institutional as well as material determinants of mobility, Gogia (2006: 359) observes, ‘the conditions of globalisation have facilitated the movement of a record number of people; individuals who are crossing international borders for work, leisure, safety and security’. Within cities, just as urban collective transport provided mobility for a wider and wider set of social groups, so too the mass production of the private car offered a type of personal mobility to the whole adult population which was formerly the privilege of the rich. Bringing mobility back to the core analysis of social life means acknowledging that mobility has at least as important a role to play in shaping social life as ‘place’, location and political boundaries, overturning what Cresswell and others term the ‘sedentarist’ basis of geography and politics (Cresswell, 2006; Kaufmann, 2005).

It is under this sedentarist assumption that mobility is conventionally seen as an epiphenomenon, a ‘derived demand’, a mere concomitant of something else such as urbanization or globalization, or a means to other activities conducted in place. Banister (2005: 224) points to the tension between transport seen as a negatively valued activity – a derived demand – and an activity with intrinsically positive values. To understand the mobility dilemma we need to bring physical mobility into the foreground. What does being able to move around quickly and freely do for the way society works? The shadow question is of course ‘how will society cope if its members cannot move around in the same way?’ We need to understand what the raw fact of vastly increased physical mobility – in simple terms the ability to travel more often and further afield – what Whitelegg (2003: 118) terms ‘the distance-intensive lifestyle’ – means for society. We need to know more about this in order to begin to comprehend what a change in mobility might mean.

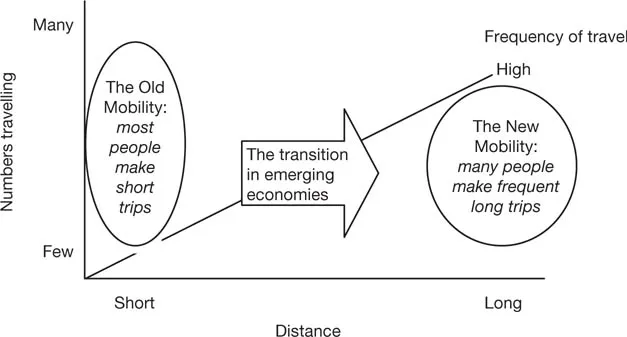

To understand the effect of mobility on society we need to recognize some of its key features. Our research leads us to define mobility in terms of three aspects. These are measures of distances travelled, frequency of travel and the proportion of the population who are travelling summed up in the diagram in Figure 1.1.

The essence of modern mobility is that high proportions of the population are travelling frequently, often over long distances. That is in contrast to the long-term historical record in which very small proportions of the population made infrequent long journeys, while the majority of the population travelled short distances frequently. Thus in the world today the experience of mobility has shifted, and is still shifting, towards the upper right hand side of the diagram. To understand mobility we need to understand this new pattern. There are a number of possible explanations that we will discuss under the conventional rubric of production and consumption.

Industrial production

Economic geographers once emphasized capital mobility as a key element of globalization. More fundamentally, it is the mobility of goods in global supply chains that is the working face of globalization. Mobility is so fundamental to production that we can perhaps think of the ‘embodied mobility’ in almost everything that is produced. Thomas Friedman (2005: 415–17) provides an example by outlining the many inter-continental links that were needed to produce and deliver his Dell notebook computer (Box 1.1).

Figure 1.1 | Distances travelled, frequency of travel and the proportion of the population who are travelling |

Box 1.1 Global trade and the Dell notebook

Thomas Friedman (2005: 415–17) tells the story of the many national and intercontinental links required to bring his Dell electronic notebook to his desk. Dell has six factories around the world spread over four continents. Surrounding every factory are supplier logistics centres that have stocks of parts supplied from all over the world. Key elements of the notebook’s hardware come from the Philippines, Malaysia, Taiwan, Germany, Mexico, Singapore, Thailand, India, Israel, and of course many different cities in China. Friedman lists them in great detail. Dell notebooks are constantly being updated and are completely redesigned about every twelve months with new hardware and software components. The key elements of the notebook come from all over the globe. This way if one supplier fails to deliver, the part can be sourced from somewhere else: ‘Every two hours, the Dell factory in Penang sends an email to the various SLCs [supplier logistics centres] nearby, telling each one what parts and what quantities of those parts it wants delivered within the next ninety minutes – and not one minute later. Within ninety minutes, trucks from the various SLCs around Penang pull up to the Dell manufacturing plant and unload the parts needed for all those notebooks ordered in the last two hours’ (ibid. 415).

Here is an example of the detailed operational planning of mobility. Friedman’s example illustrates the logistical logic in which labour skills in many places around the world are coordinated in production. The Dell notebook is just one of the thousands of commodities produced that flow through centrally planned global supply chains of this sort.

Global s...