![]()

PART I:

INTRODUCTORY MATERIALS

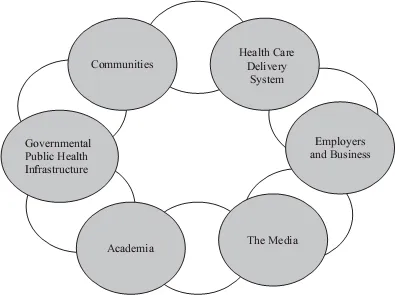

Figure reprinted with permission from The Future of the Public's Health in the 21st Century. ©2002 by the National Academy of Sciences, courtesy of the National Academies Press, Washington, DC.

![]()

Chapter 1

The Nomenclature of the Community:

An Activist's Perspective

Joshua L. Ferris

INTRODUCTION

The lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community is an extraordinarily diverse group of people. Along with the community comes an alphabet soup of names and terms. Terms such as LGBT, GLBT, queer, homosexual, and gay and lesbian can be used interchangeably. The importance of this nomenclature rests on the individual addressing the community and his or her personal identity and politics. Likewise, one should not assume that these terms completely capture everyone who identifies as LGBT. Recently, while attending a conference concerning this population, I overheard the term GLBTQQCSI (gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, confused, supportive, and intersexed). This acronym was clearly alarming, but it should not frighten people from attempting to learn and use much of the jargon associated with the LGBT community at present. This term was merely a way for the conference official to include a very diverse group of individuals. Terms are not the foundation of any community, but nonetheless vocabulary is quite relevant when attempting to address and target a community for disease prevention and health promotion.

For effective health advocates, terminology is an essential part of their ability to connect with the community. It is a matter of personal opinion for an individual to decide for himself or herself whether to use the newest and freshest terms or whether the terms he or she is using are the most effective to address the targeted population. Those working with the community tend to use LGBT or GLBT. For the sake of writing, LGBT will be consistently used henceforth, because it is a commonly recognized term and it is the preferred parlance of this book.

What is the LGBT community?

Who are its members?

What is its function in the greater societal model?

These are a few very broad and complex questions that arise for health officials when they begin to work with the LGBT community. Currently, almost everyone is familiar with the idea of someone identifying as LGBT. It may not be a personal or close relationship, but most people have heard of NBC's Will & Grace, Ellen DeGeneres, or MTV's The Real World. LGBT people are all over the airwaves and are part of most families’ televisionwatching lineup.

It could be argued that media exposure has been one of the most beneficial changes for the LGBT rights movement. People are now more comfortable with the LGBT community than they were twenty years ago. As great as this is, an unheard disclaimer accompanies all of this mainstream attention. Television is not the flagship for the LGBT community (or any group, for that matter). The fact that all of the television programs have a consistent character type only narrows the public's actual experience of the queer community. Not everyone is an upper-middle-class white man, secure with his sexual identity, who has both accepting family and friends. We must realize that these programs are for entertainment purposes and, for the most part, represent only the characters in the show, displaying very little of the true diversity of the LGBT community.

People from every race, nationality, gender, class, and political and religious affiliation are represented in the LGBT community. Gay and bisexual men tend to be categorically stereotyped as flamboyant and meticulously dressed. Lesbian and bisexual women tend to be categorically stereotyped as “butch,” flannel-shirt-wearing with short hair. These stereotypes, of course, are not at all accurate. Gay and bisexual men and lesbian and bisexual women are as different and unique as heterosexual men and women. Reducing any people to a base stereotype is incorrect and potentially dangerous. It is important to note, however, that some men and women fit very neatly into the gay and lesbian stereotype, and this is perfectly acceptable. It is just as acceptable as a gay man who plays rugby or works construction. Stereotypes, though sometimes accurate, represent only a small piece of the community.

Being part of the community is a matter of self-identification. To identify as a gay man or lesbian woman is a choice made when a person is comfortable with his or her affectional preference. To be LGBT is not to be understood as a choice; the choice lies in one's decision to identify as LGBT. There are people who choose to have sex with people of the same gender or have same-gender attractions but who do not identify as a part of the LGBT community. Conversely, there are people who identify with the LGBT community whose primary means of identification is neither sexual nor affectional preference. Identifying with the LGBT community is not limited to identities based on sexual attraction, but rather, because of an emotional attraction or mental alignment. From my interaction with parents of LGBT children, these parents feel very much a part of the gay and lesbian community.

COMING OUT

“Coming out of the closet” is a buzz phrase that most people have heard. This is the process by which LGBT people acknowledge that they are not exclusively heterosexual. Many people self-identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual based upon their sexual attraction. Others identify with the LGBT community. Two very important phases characterize the coming-out process. The first is coming out to oneself. This is the time in which many people realize that their personal attractions and fantasies are valid and that it is acceptable to express these attractions. For many, it is the first time a person says, “I'm gay.” This moment is a very serious one, because for many people it drastically changes their world. This is because most people live in a society where heterosexuality is considered the norm.

Most of us have been raised in a severely heterosexist world. Heterosexism is the assumption that society by default is heterosexual and that heterosexuality is superior to any other identity. Our culture presupposes that humans are naturally heterosexual. Heterosexuals do not have to come out the way LGBT people do. Heterosexism derives itself from the assumption of heteronormativism. Heteronormative is loosely defined as the idea that heterosexuality is normal and anything else is not normal or natural. This of course sallies forth many scientific, political, and philosophical questions, such as “what is normal?” Michael Warner, in his book The Trouble with Normal (1999), looked at American heteronormative culture. Warner is witnessing LGBT people's fight for inclusion in what society considers normal. Normalization for Warner includes the legal right to get married, the fight against the stereotype of promiscuity, and the greater idea that LGBT people are trying to assimilate into normal society.

This view stands apart from the debate on assimilation versus separation. Is heterosexuality normal or is it merely the pronounced norm in society? It can be assumed that the majority of LGBT people are inclined toward assimilation. People in general want to be part of the society they are familiar with and do not want to be categorically stereotyped and stigmatized. A few people who fall along the lines of Warner's thesis believe normal society should not be the goal for which to strive. They believe LGBT people have a unique opportunity to redefine society's present relation with the entire spectrum of sexuality. Of course, this is by no means a definitive argument that all people take sides in, but rather one reserved for theorists and activists.

The second phase is coming out to people the person encounters. This process is unfortunately lifelong, and it rarely gets easier. For many people this is an extremely difficult process. Questions such as “Will my sexuality be an issue with this person?” and “Is this portion of my life relevant to the relationship I have with this person?” are prevalent. LGBT people answer these and similar questions differently all of the time. For many, it is important for people to know that they identify as LGBT, while others consider it part of their private lives. This is a matter of personal preference and should not be subjected to outside judgments.

The coming-out process is very self-empowering. It gives many people a new sense of self-confidence and personal control that they may not have felt before. Once people come out to themselves, they wonder if it will completely turn their worlds upside down. Many people feel as though they are turning their backs on the world. This varies from person to person, but it is an extraordinarily important moment in a person's life. If someone comes out to you, it is because he or she trusts you. You should try to be supportive. Realize that he or she is not a different person, but that you are now privileged to know the same person in more depth.

The period for coming out is ongoing and has no age boundaries. People will identify as LGBT when they are elderly and as early as preadolescence. The younger end of the spectrum has been something of tremendous research and focus in recent years. As the LGBT community has become more mainstream, the coming-out age has gotten younger. Adolescents for the first time are experiencing LGBT people during the time when they first start to think about sexuality. They are not so isolated as previous generations.

For those of us privileged enough to attend a university after high school, this is a moment when many people begin to realize that they are not heterosexual. It is the first time many young adults have freedom in their daily routines. This freedom allows some students to act on feelings or interests that may have been suppressed when they were in high school. Along with this freedom comes the opportunity to experience a diverse academic environment. People from all lifestyles, places, and cultures are confronting one another all of the time. This is for many LGBT students the first time they may meet other LGBT students.

Many unique factors are at work for people of color who are going through the coming-out process. When people identify as LGBT, they have then subscribed to a personalized label. Does this mean that this is one's only label? Is it the primary label? Many LGBT people of color battle this with themselves and with their communities every day. These questions are never easily answered but have become the basis of much writing and research in current years. A move in the public health sector is attempting to reconcile some of these differences. These differences are tremendously complicated by the multitude of stereotypes that follow any marginalized community.

STEREOTYPICAL LIFESTYLES

Bars and Clubs

The idea that members of the LGBT community live fast-paced and extraordinary lifestyles is pervasive. Socializing seems to revolve around bars and dance clubs, where life is everything but boring. This stereotype is present in both the heterosexual and LGBT community. For those members of the LGBT community who do enjoy going to bars and clubs, many times this becomes the community norm to them. Those people who do not enjoy crowded dance clubs or the typical bar scene are many times forgotten. A portion of this can be attributed to the media; successful television rarely reflects the lifestyle of the average person—LGBT people included.

This being said, something can be recognized about bars and clubs within the LGBT community. From the 1950s through the 1970s there were very few places to meet other LGBT people other than bars. Bars provided a safe space for LGBT people to be open about their sexuality and to meet other LGBT people. Bars, though seemingly prominent, play no different role than they do in the heterosexual community. Bars are everywhere, and some people choose to go and some people do not. Some LGBT people choose to go to heterosexual bars, and some heterosexual people like to hang out in LGBT bars. There are no standards here, and bars by no means stand as a foundation of the LGBT community.

The Gay Ghettos

In many cities you will find a neighborhood where the population density of LGBT is higher than it is in other parts of the city. Many times you will hear these areas called “gayborhoods” or “gay ghettos.” These will most commonly be found in large metropolitan areas. Most people find comfort in numbers. Many people would rather live in a neighborhood where their sexuality is not a cause for concern or question. Not every urban area in the world has a strongly defined LGBT area, but many do. The Castro in San Francisco, Soho in New York, and West Hollywood in Los Angeles are some of the most famous LGBT neighborhoods.

Politics

This population density has been one of the major factors in the development of the LGBT community as a political base in America. As LGBT people began to move closer together and form their own neighborhoods, they gained political power to elect local officials. The stereotype of LGBT people as liberal Democrats may be one of the largest misunderstandings that the community deals with. This is a stereotype inside and outside the borders of the community. With the rise of groups such as the Log Cabin Republicans, the Republican Unity Coalition, and the Lavender Greens one can easily see that LGBT people are not exclusively Democrats. One can never assume that LGBT people are diehard liberals with total allegiance to the Democratic Party.

Affluence

Another stereotype associated with the LGBT community is affluence. This has been perpetuated by the public knowledge that the LGBT community has become a very prominent target for marketing strategists. It is true the LGBT community has become a specific market for most industries, but this does not mean that every LGBT person has disposable income. In the past LGBT people typically did not have the usual expenses associated with parenthood. This allowed more disposable income for home improvement, lifestyle events, and entertainment. However, in recent years the phenomena of gay adoptions have become more frequent, and there are many studies right now about LGBT people in economically depressed communities. In the near future, the stereotype of affluence may be the first to be put to rest.

GENDER IDENTITY

Although sexual orientation and identifying with the community are important, many issues of gender arise. Some people in the community challenge the typical gender roles constructed by society. This challenge of gender has seeped into the mainstream, especially in fashion. Transgender is a word that describes people who express their gender differently from established stereotypes. This term is relatively new in the English lexicon and does not exist in The Encyclopedia of Homosexuality (Dynes, 1990). It is something of an umbrella term that tends to include people who cross-dress or anyone who displays gender characteristics different from what may be expected and considered normal by society. Transgender is part of the concept of gender identity.

For many people this idea is very difficult to understand. Gender is a very interesting idea that has been confused for a very long time with sex. Sex and gender are very different terms that describe very different concepts. Sex is determined by our genetic and physical makeup at birth. This is a scientific and medical definition. Gender, since the 1970s, has distinguished itself from biological sex as the social distinctions between masculine and feminine behavior. Generally, our society raises children in a fashion specific to the assumed characteristics of the sex of the child. Some people may have been born biologically male but they feel female. These people have the right to express themselves as who they are, and this expression should not be hindered because of their biological sex.

It is important for people to realize that gender identity is not related to sexual orientation. Sexual orientation is, as described, about the biological sex to which we are attracted. Gender identity is how we express our gender. Dealing with transgender issues is sometimes very different from dealing with LGBT issues. Many transgender people are attracted to people of the opposite gender. Not all LGBT issues are relevant to the transgender community. The issue of transgenderism will be explored in more detail in Chapter 7.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, here are a few stone-cold facts that define the LGBT community. The community is composed of people who feel that their gender and sexuality are different from that of mainstream society. It is most important to realize that all people are extremely complex, and respecting diversity is of the utmost importance. The LGBT community has no clear boundaries and is being redefined every day. Terms are changing and definitions are constantly evolving.

QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER

1. How do LGBT people that you know self-identify?

2. What are terms and acronyms used in your community to address the LGBT community?

3. Are these terms descriptive, empowering, marginalizing, community building, political, slang, or destructive to the LGBT community?

4. Are there terms used in your agency or by the agency's staff that LGBT people may think are negative or offensive?

5. What practices has your agency implemented that have, consciously or unconsciously, constructed terminology barriers that may prevent members of the LGBT community from accessing services?

6. The best method to identify a population is to ask them how they wish to be identified and use those terms. How does your agency use terminology to include members of the LGBT community?

7. How can your agency use terminology to facilitate the LGBT community's comfort while accessing services?

REFERENCES

Dynes, W.R. (Ed.). (1990). The encyclopedia of homosexuality. New York: Garland Publ.

Warner, M. (1999). The trouble with normal: Sex, politics, and the ethics of queer life. New York: Free Press.

![]()

Chapter 2

The Role of Public Healthin Lesbian,

Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health

Patricia D. Mail

Walter J. Lear

INTRODUCTION

“Public health” is thought of by many individuals, regardless of their sexual orientation, as combating contagious epidemics, educating about cancer and heart disease, providing HIV and AIDS services, and controlling health hazards in our food, water, air, ...