![]()

Suicide

The problem

1.1. Introduction

- Every year, almost one million people die from suicide; that's one death every 40 seconds.

- In the UK, the suicide rate for men is three times that for women.

- Those aged between 25 and 44 years are most at risk.

- Social factors shown to influence suicide rates include unemployment, divorce and religion.

- Having a mental health problem makes a greater contribution to a person's risk of suicide than any social factor, with 9 out of 10 suicides experiencing mental health problems.

- The risk of suicide is particularly elevated for individuals experiencing depression, psychosis, traumatic stress, substance misuse or personality disorder.

- Experiencing multiple ‘co-morbid’ mental health problems further compounds this risk.

- A history of previous suicide attempts remains one of the most important and clinically relevant risk factors, which persists throughout an entire lifetime.

1.1.1. Rate of suicide

- Every year, almost one million people die from suicide; that's one death every 40 seconds.

- Over the past 60 years, the rate of suicide in the UK has remained stable at between 7 and 13 deaths per 100,000 persons.

- Suicide rates are relatively higher in Scandinavia and former Soviet Republics and lower in Mediterranean countries.

- Social factors shown to influence suicide rates include unemployment, divorce, substance misuse and religion.

According to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates, each year approximately one million people die from suicide and 10 or 20 times more people attempt suicide worldwide. This represents one death every 40 seconds and one attempt every 3 seconds, on average (www.who.int/whosis).

In the UK, suicide is the third largest cause of death. In 2008, there were 5706 suicides, an increase of 329 (6%) from the previous year. However, over the past sixty years, the total number of suicides in the UK has changed little. In 1950 there were 4660 self-inflicted deaths, a difference of only 20% from 2008. Despite slight variation each year, the suicide rate over this time period has remained between 7 and 13 persons per 100,000 persons since 1950 (ONS, 2010).

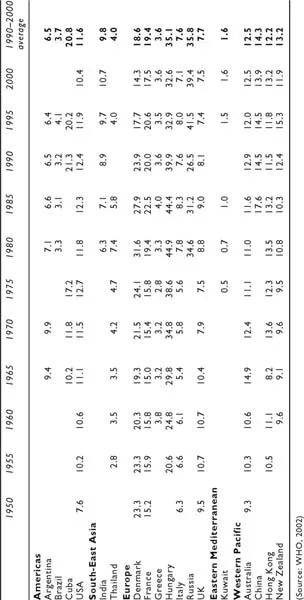

The rate of suicide varies widely across and within the different continents of the world. Table 1.1 provides the suicide rates per 100,000 of a small selection of countries from the various Regional Offices of the WHO. Within some regions, all countries seem to maintain similar rates. For example, in the Western Pacific region, which includes Australia, New Zealand, China and Hong Kong, all countries have average suicide rates per 100,000 for 1990–2000 of between 12 and 15 persons per year. Similarly, Argentina and Brazil have an average rate of 6.5 and 3.7 persons per year, respectively. And yet, also in the Americas region, Cuba has an average rate of over 20 persons per 100,000 per year (WHO, 2004).

In Europe, variation across countries is also quite marked. For instance, Denmark has an average rate of over 18 persons per 100,000 per year, much in line with its Scandinavian neighbours. Even higher rates have been observed over the past few years in Russia and many of the former Soviet Republics, with rates of more than 40 persons per 100,000 per year. Conversely, the southern European countries of Italy and Greece have observed much lower suicide rates of 7.6 and 3.6 per 100,000 persons, respectively.

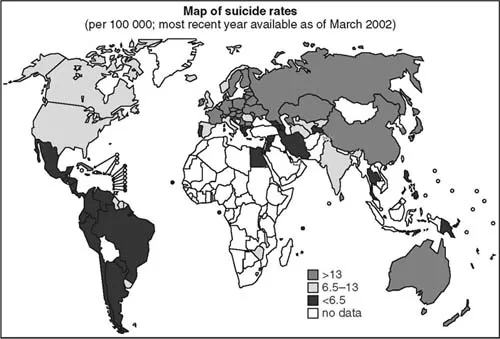

It must be noted, as seen in Figure 1.1, that little data is collected from countries on the African continent. Therefore, little can be reported on how these particular countries compare to the rest of the world.

Figure 1.1 Map of suicide rates (Source: www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/suicideprevent/en/index.html [accessed 20 July 2012])

Table 1.1 Suicide rates (per 100,000) by country

Over the past 100 years, the rates of suicide across nations have varied although the rank ordering of countries has remained relatively constant (Diekstra, 1995). This suggests that suicide rates are likely to be determined by persisting cross-national differences including traditions, customs, religions, social attitudes and climate.

Durkheim (1897) suggested that suicide rates may be influenced by the extent to which individuals are integrated within society, arguing that ‘social integration could be achieved through family support together with religious, political and work affiliations’. This theory has been extensively researched over the past 100 and more years, with supportive evidence stressing the importance of social factors such as unemployment, divorce, substance misuse and religion, in explaining national differences and trends in suicide (Gunnell et al., 1999a; Lester, Curran & Yang, 1991; Makela, 1996; Lester, 1997). Societal changes, such as economic crises or periods of war, have also been recognised as contributing to changing patterns of suicide. A number of studies have identified an association between a country's economic and societal factors with time trends in overall population suicide rates (Weyerer & Wiedenmann, 1995; Low et al., 1981; Lester & Yang, 1991).

With respect to religion and its influence over suicide, Durkheim concluded that suicide rates should be lowest among followers of those religions that closely integrate the individual into collective life. For example, among Christians, Protestants would be less protected against suicide than Catholics, due to the higher state of individualism in Protestantism. Neeleman et al. (1997) investigated whether a negative association between religion and suicide is attributable primarily to social cohesion provided by religious organisations (Durkheim, 1897) or to an association of religious belief with reduced tolerance of suicidal behaviour (Stack, 1983; Stack & Lester, 1991). Religious and socio-demographic variables were obtained from a random sample of adult participants of all 19 non-Eastern bloc European countries, Canada and USA (total n = 28,085), which took part in the 1990/1 World Values Survey (WVS Study Group, 1994). The study reported that suicide rates relate more strongly to levels of religious belief and suicide tolerance than to church membership or attendance. The findings supported the religious commitment or cognitive dissonance model, which states that ‘commitment to a set of personal religious beliefs may be more important in guarding against suicidal behaviour than social integration in religious groups’ (Neeleman et al., 1997, 1169).

It is, however, unlikely that one single factor can be clearly implicated as having sole influence over suicide rates, since the causes of suicide are thought to be complex and multi-factorial with all such factors more likely to represent fundamental societal changes (Gunnell, et al., 2003).

1.2. Suicide and social factors

1.2.1. Gender and age

- In the UK, the suicide rate for men is three times that for women.

- Historically, older people experienced higher rates of suicide, although more recently, those aged between 25 and 44 years have become the most at-risk age group.

- This shift in risk associated with age has been attributed to increases in the rate of unemployment, divorce, substance misuse and alcohol consumption in the younger age groups.

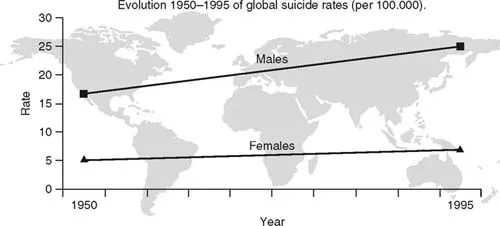

In the UK in 2008, the suicide rate for men (18 suicides per 100,000) was more than three times that for women (5 suicides per 100,000) (ONS, 2011). On a global scale, this difference in rates between males and females has been steadily increasing over the past 50 years (see Figure 1.2). The global suicide rate for females has remained almost constant at around 5 suicides per 100,000 per year. However, the rate for males has increased from 16 per 100,000 in 1950 up to 25 per 100,000 by 1995, an increase of nearly 60% (WHO, 2002).

Figure 1.2 Evolution 1950–1995 of global suicide rates (per 100,000) (Source: www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/evolution/en/ [accessed 20 July 2012])

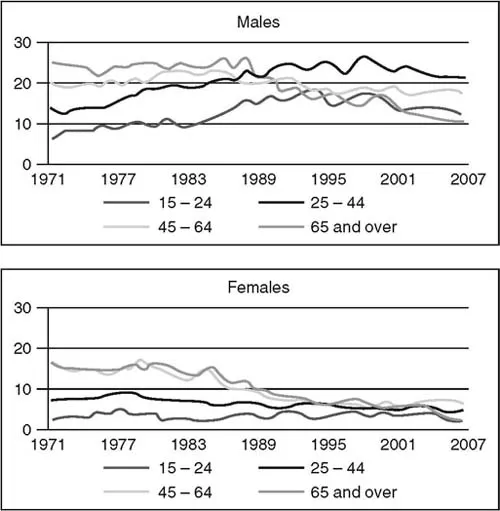

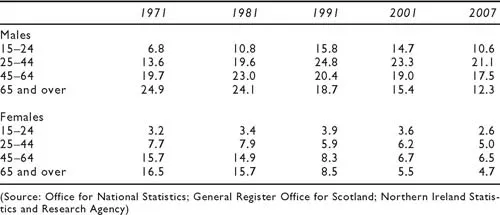

Figure 1.3 Suicide rates by sex and age (per 100,000) (Source: ONS, 2011)

Trends in suicide rates have varied by age and sex in the UK, although in each age group, males generally have a higher suicide rate than females (Figure 1.3). In the 1970s and 1980s, there was a steady increase in the rate of suicide by men across all age groups. This increase was particularly noted in the 15–44 year age group (Table 1.2), although older men maintained the highest suicide rates. During this period, older women also had the highest suicide rates for females, although the rate for females aged 45–64 years was only slightly less. In more recent decades, the suicide rate for older men has declined, with the rate for 2007 of 12.3 per 100,000 men being less than one-half of its peak. The rates for women aged 45 and over have also declined during this time. In more recent decades, there has been a decrease in the suicide rate for males across all age groups; however, the fall in the younger age groups has not been as dramatic as previous increases, leaving the 25–44 year age group with the highest rate of suicide in males. In females, the rate of suicide has also fallen in all age groups, with an especially marked decrease in the older age groups.

The difference between these rates can be explained in various ways. Schmidtke et al. (1996) suggested the lower suicide rate in females is misleading since men have a higher rate of completed suicide, whereas women have a higher rate of attempted suicide. This suggestion is underlined by Mann (2002), who observed that

men tend to use means that are more lethal, plan the suicide attempt more carefully, and avoid detection. In contrast women tend to use less lethal means of suicide, which carry a higher chance of survival, and they more commonly express an appeal for help by conducting the attempt in a manner that favours discovery and rescue.

The preferred choice of method could be influenced by gender differences in the occurrence of impulsive—aggressive personality traits, a potentially important risk factor for suicide (Dumais et al., 2005).

The shift towards a younger high-risk age group has been observed on a global scale. According to the WHO, in 1950, 60% of suicides occurred in persons aged 45 years and over. By 1998, this proportion had fallen to 45%. Several explanations have been put forward for this new high-risk age group, including increases in male unemployment, increases in the number of divorced men who had not remarried, increases in the rate of substance

Table 1.2 Suicide rates for UK: by age and sex (per 100,000)

misuse and alcohol consumption, and the changing role of women to becoming more independent, more likely to be lone-mothers and preferring to get married older (Pritchard, 1992; McClure, 2000). All of these factors may have consequential effects on the mental health of young men and the rate of suicide.

1.2.2. Unemployment

- Suicide is related to unemployment, especially for younger age groups.

- Being unemployed is associated with an eight-fold increase in suicide risk compared to full or part-time employment.

- The increased risk associated with unemployment may reflect an important relationship between poor social integration and suicide.

In Great Britain, male suicide rates increased during economic recession but the opposite occurred in females (Crombie, 1989; Charlton, et al., 1992). This increase was in line with most other European Community countries (Pritchard, 1992). To examine the association between unemployment and suicide over a period spanning ‘the two great economic recessions’ of the last century, Gunnell et al. (1999) identified all suicides, in 15–44 year old men and women, between 1921 and 1995. A time-series analysis of this data identified an association between suicide and unemployment in males and females aged 15–44 years. The association was observed to be most highly significant in the younger age bands for both males (15–24 years: coeff. 0.20, 95%CI 0.05–0.35, p = 0.011; 25–34 years: coeff. 0.18, 95%CI 0.08–0.28, p = 0.001) and females (15–24 years: coeff. 0.46, 95%CI 0.18–0.73, p = 0.002). However, Gunnell et al. (1999) highlight the ecological fallacy that the association found for population data cannot be used to imply that individuals who complete suicide are themselves unemployed.

In another study of suicide and employment, Hawton et al. (2001) examined all suicides aged 15 years and over in the Oxfordshire area, between 1985 and 1995. A significant association was found between male suicide rates and a measure of socio-economic deprivation, which included the proportion of unemployed persons, although this effect was attenuated when controlling for a measure of social fragmentation, which included population turnover and the proportion of unmarried persons.

Finally, Duberstein et al. (2004) reported on a case-control study of the association between suicide and social integration among those aged over 50 years. The study identified 137 suicides in two counties within the state of New York, USA, between December 1996 and January 2001. Adopting a psychological autopsy approach, the authors interviewed informants for almost two-thirds of the suicides (86, 63%) along with informants for a group of randomly selected controls matched to cases on age, gender, race and county of residence. In terms of employment status, Duberstein et al. (2004) found the risk of suicide associated with being unemployed was more than eight times that of those in full or part-time employment (OR = 8.27, 95%CI 2.90–31.61).

In summary, there appears to be support for unemployment as a risk factor for suicide. However, whether unemployment is a cause of suicide, per se, or more of an indicator of lower social integration remains to be shown.

1.2.3. Marital status

- Married people are less likely to die from suicide than single, divorced, separated and widowed persons.

- For women, being a parent of a young child may actually be the protective factor, rather than being married per se.

- Being widowed at a younger age elevates a person's suicide risk, more so than at an older age, as it is viewed as an ‘off-time’ event with greater personal adjustment required.

Another demographic factor frequently cited as linked to suicide is that of marital status, with married persons experiencing lower suicide rates than single, divorced, separated and widowed persons. The relationship between suicide and marital status has been found across various populations, including the UK (ONS, 2010), the USA (Kessler, Borges & Walters, 1999; Kposowa, 2000), Finland (Heikkinen et al., 1995) and Denmark (Qin et al., 2000). However, there may be subtle gender differences within this relationship, since being a parent of a young child appears to explain the apparent protective effect of marriage for women rather than married status, per se (Hawton, 2000; Duberstein et al., 2004). Why such differences occur between divorced men and divorced women has attracted some theoretical interest. It may be that marriage confers health advantages that divorced persons lack. Perhaps marriage offers security and social support, and as a result, the married may be happier than the divorced (Verbrugge, 1979).

Durkheim (1897) explained the relationship between marriage and suicide using the concept of social integration, referring to ‘the strength of the person's ties to society and the stability of social relations within that society, marriage being one of them’. Consequently, when a marriage ends, a sudden and unexpected change occurs in a person's social standing. The divorced or widowed person no longer feels a sense of cohesiveness and support as was once provided by...