![]()

PART I

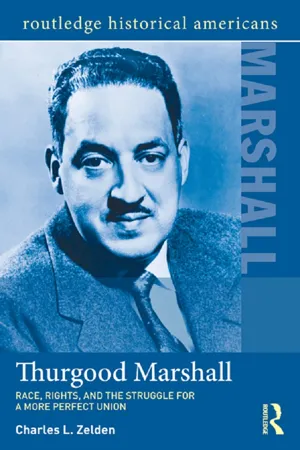

THURGOOD MARSHALL

![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE EDUCATION OF THURGOOD MARSHALL

Thurgood Marshall was born into a world in which race mattered, a world in which the color of your skin defined who and what you were to the world at large. Education, talent and skill, willingness to work hard and to be a good citizen, all this meant little if your skin color was dark. As an African American in the American South of the early twentieth century, Marshall grew up in a world that by law and custom imposed strict limits on his life choices. He was limited as to where he could live, work, and eat; his public associations and behaviors were sharply circumscribed; government existed not to serve his needs and wants, but as an agent of control and suppression. His was a world full of constraints and burdens, of threats and restrictions, all on account of his race.

It was not supposed to be like that. Following the Civil War, three constitutional amendments promised African Americans freedom, citizenship, and the right to vote, backed by guarantees of equal protection of the laws, due process of law, and the power of Congress to enforce those constitutional guarantees “by appropriate legislation.” Nor did Congress shirk its enforcement duties; between 1866 and 1875, Congress passed two civil rights acts and three enforcement acts all designed to carry out those constitutional promises. This was in addition to four Reconstruction acts that provided military force in support of civil authorities as Congress attempted to reshape the South’s social, political, and racial structures.

At first Reconstruction seemed to work. In 1867 and 1868, blacks across the South allied with white Republicans to elect large numbers of delegates, approximately a third of them black, to new state constitutional conventions. These Republican-dominated conventions, in turn, wrote extremely liberal constitutions recognizing full civil rights for black Americans. Hundreds of thousands of blacks quickly registered to vote; and in subsequent elections they exercised this right, often voting for black candidates. Ultimately, some fifteen hundred African Americans were elected to office; sixteen of them to Congress; more than six hundred to serve in the state governments organized under the Reconstruction state constitutions; and the rest holding local and county offices.

Yet by the time of Thurgood Marshall’s birth in 1908, these gains were largely gone. The vast majority of Southern whites would not accept the concept of racial equality or its legal consequences. As early as 1866, white terrorist organizations—the Ku Klux Klan the best known of many—launched a wave of race-based violence and terror that spread across the South. These agitators broke up Republican Party meetings, African American church gatherings, and classes in black schools. They attacked and killed prominent blacks. Others were “beaten, flogged, [and even] mutilated.” Before long, even average blacks faced assault for being “insolent” toward whites or for “not obey[ing] the orders of their former masters, just as if slavery existed.” The victims of these murderous rampages numbered in the thousands.1 In Texas alone, between 1865 and 1868, one percent of all African American males between the ages of fifteen and forty-nine were the victim of white on black violence. In the worst outrages, white mobs attacked entire groups of blacks, terrorizing most and killing many. In one 1873 incident, in Colfax, Louisiana, a white mob attacked and trapped one hundred and fifty blacks in the county courthouse for three days; before it ended, the mob had massacred a hundred blacks—some fifty after they had tried surrendering under a white flag.

This campaign of terror combined with more overt electoral intimidations and frauds to frighten African American voters away from the polls in the 1870s. Combined with the negative political effects of bad economic times, legitimate claims of corruption against state Republican administrations, and heavy campaigning by Democrats among the region’s white voters—all of which increased the Democratic vote—opponents of Reconstruction defeated Southern Republican governments across the South. Once in power, white Southern Democrats set about dismantling the constitutional, legal, and political reforms adopted during Reconstruction. Their objective was to re-impose a system of political, economic, and social control over blacks resembling that of slavery, though without actually reimposing slavery. In time, this effort would acquire the name of “Jim Crow” segregation.

When fully put into effect, Jim Crow segregation combined repressive government power, racist cultural and social norms, and extralegal violence to shape not only political relationships between the races, but social and economic ones as well. At its heart, Jim Crow meant imposing absolute control over the region’s African American population—control at all costs, by any and all means—with the specific intent of keeping power in the hands of those who already had it (Southern whites) and away from those who might make claims upon it (Southern blacks).

The practical result of such repressive efforts, formal and informal, was the eventual expulsion of African Americans from most aspects of Southern public life. Blacks could not vote or hold office. They were barred from riding in the same train cars as whites, and later they were exiled to the back of public buses. The racism of white unions and management barred the vast majority of blacks from the best types of employment. So too did laws throughout the South that prevented blacks from working in the same rooms with whites or even using the same doors and stairways that white workers used. Prominent black leaders—in fact, any blacks who spoke out too loudly against the limitations imposed on their lives by segregation—faced the daily threat of death by lynching. Meanwhile, black schoolchildren received an inferior education, while neither they nor their adult relatives could frequent the same parks, swim in the same pools, or drink at the same water fountains as whites.

It did not happen all at once. Laws and rules imposing segregated facilities entered the statute books piecemeal. Southern segregationists were careful not to run afoul of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments—explicitly. If they went too far or acted too aggressively in limiting black rights, Southern whites risked a national backlash and federal intervention. There were also serious political divisions within the Southern white population affecting the pace and shape of Jim Crow’s development across the South. So too, violence against African Americans ebbed and flowed over time and from region to region in response to specific local and regional conditions.

Nor did Southern blacks accept the imposition of segregation quietly. African Americans fought against rules that limited their political, economic, and social status. In many parts of the South, these efforts were successful for a time: through the rest of the nineteenth century, hundreds of thousands of Southern blacks remained registered to vote, with tens of thousands voting on a regular basis; a few blacks even kept their elected positions until the end of the century.

In the end, however, theirs was a losing fight. Rulings by the U.S. Supreme Court in such cases as U.S. v. Cruikshank and U.S. v. Reece in 1876, the Civil Rights Cases in 1883, and especially Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 and Williams v. Mississippi in 1898 severely limited the reach of the Reconstruction Amendments, freeing Southern whites from fear of federal intervention. Political differences among the region’s white population, in turn, were ultimately mitigated by a shared consensus on race or made irrelevant by voting rules that effectively disenfranchised poor whites along with blacks. By the 1890s, political leaders in the Southern states were confident enough to begin writing Jim Crow segregation not only into their state constitutions but also into their county and city codes, criminal statutes, and civil ordinances. At the same time they adopted ever more extreme rules for voting that effectively disfranchised virtually all black voters. By the time of Thurgood Marshall’s birth in Baltimore, Maryland, on July 2, 1908, the legal codification of Jim Crow was complete, and with it the marginalization and oppression of the South’s African American citizens.

For the young Throughgood Marshall (at age six, Marshall shortened his name to Thurgood, because his name was just “too damn long”).2 Jim Crow segregation was an established, if not always accepted, part of the world he lived in. The schools he attended were segregated; the stores his family shopped in were mostly segregated; the neighborhoods his family could live in were increasingly segregated. Throughout Baltimore, he saw signs posted that said “whites only.” Few public or commercial buildings allowed blacks to use bathrooms, elevators, or, in many instances, even the front door. As a young man, Marshall experienced firsthand the dilemma such rules posed: unable to find a toilet open to blacks anywhere downtown, he was forced to rush home on the trolley to relieve himself; he almost made it—ultimately (and embarrassingly) losing control of his bladder on the front doorsteps of his home.

Segregated facilities also meant inferior facilities. Baltimore’s black schools, for instance, were smaller and more crowded, lacking such amenities as cafeterias, gyms, libraries, or even enough books for every student as compared to the white schools. The school year for black students was one month shorter than it was for whites. By the time Marshall attended high school, the city’s sole black high school was so overcrowded that school administrators were forced to split the student body into two groups and run half-day sessions. When, a year after Marshall graduated, a new high school for black students was being built, construction was halted for a time because the plans included a swimming pool. The Baltimore School Superintendent stopped the project because (as Marshall recalled) he thought that “Niggers didn’t deserve swimming pools.”3

Still, for most of Marshall’s early childhood the burdens of segregation sat lightly on his shoulders. He was born into a loving extended family whose members worked collectively to shield him and his older brother William Aubrey from the worst of the effects of Jim Crow. Marshall’s parents and grandparents were a part of the black urban middle class. Both of his grandfathers served in the U.S. military and returned to Baltimore to open successful grocery stores. Both grandmothers were college-educated schoolteachers. Marshall’s father, William Canfield Marshall, had jobs as a Pullman porter on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and as head steward at a country club (both very well-paying jobs for an African American in the early twentieth century). His mother, Norma Williams Marshall, was a schoolteacher, like her mother before her. The family would face times when money was tight (such as when his father was ill and could not work), but the young Thurgood Marshall did not lack for material possessions or face physical or economic hardship.

When Marshall was in elementary school, his family lived on Division Street in Old West Baltimore, an integrated neighborhood that included African Americans and white immigrants from Russia, Italy, and Germany. Later, the Marshalls moved to a five-bedroom brick townhouse on Druid Hill Avenue, a segregated black neighborhood, but one where many of Baltimore’s upper-class and middle-class blacks lived. In both places, Marshall found himself in a community that stressed coexistence rather than dissension. This was especially the case during his younger years in Old West Baltimore. The Marshalls took full advantage of living in an integrated neighborhood. One of Thurgood’s earliest childhood friends was a white boy who lived next door. His family often shared dinner with their white neighbors. As a child, Marshall worked for a white Jewish grocer, delivering groceries in his red wagon for ten cents a day. Later in life, Thurgood would experience his father’s close friendship with a white police officer. This intimate, friendly contact between the races was not the norm in the segregated South, but it was for the Marshalls.

The young Thurgood’s personality, in turn, seemed a perfect fit for the comfortable and relaxed surroundings of his youth. His nickname as a child was Goody. “He was always a smart, alert little fella,” recalled one of his aunts. “He was full of life and laughter.4 Marshall was a gifted storyteller and a prankster. When he got into trouble, it was usually for talking, laughing, and pranks, not for fighting. In high school, Marshall was repeatedly sentenced to the school’s basement to memorize sections of the U.S. Constitution for his pranks and talking. “Before I left that school,” Marshall recalled, “I knew the whole thing by heart.”5 This didn’t mean that he couldn’t play tough. As Marshall recalled, “[W]e lived on a respectable street, but behind us were back alleys where roughnecks and the tough kids hung out. When it was time for dinner, my mother would go to the front door to call my older brother. Then she’d go to the back door and call me.”6 But given a choice, Marshall would rather argue his way out of trouble than fight.

Marshall’s father honed his son’s natural gift for argument and debate at the dinner table. Willie Marshall, who had not graduated from high school but who had a love of learning, regularly attended court proceedings when he was free from work (often with Thurgood tagging along), listening intently as the lawyers argued their cases. He then would come home and use the rhetorical tactics he heard in court in discussions (which quickly turned into arguments) with his sons. Just holding a belief was not enough; Willie demanded that his sons logically back up any arguments they made. Marshall identified this regular grilling as the source of his interest in the law and in pursuing a legal career: “Oh yes, we talked about the law. We fussed about it and argued and carried on. I got the idea of being a lawyer from arguing with my dad.” So although Willie never actually told Thurgood to be a lawyer, “he turned me into one. He did it by teaching me to argue, by challenging my logic on every point, by making me prove every statement I made.”7

Still, try as they might, Marshall’s family could not fully shield the growing Thurgood or his brother from the reality of living in the segregated South. Though Old West Baltimore was an integrated neighborhood, and the Marshalls had good relations with their white neighbors, most of the local shops were owned by whites and these shopkeepers followed the unwritten rules of segregation: African Americans could shop there, but they could not try on clothes in the store or receive service when a white patron was present; some shop owners would not even allow blacks to enter through the front door unless they were so light skinned that they could pass for white. Thurgood’s uncle, Fearless Williams, would take Marshall for Sunday car rides to the Eastern Shore, each time making sure to pack extra gasoline and food for the ride; soon Thurgood realized that his uncle was taking these steps because the towns along the shore did not serve food to blacks, nor was it safe for them to get stuck in these towns overnight. More troubling were the race riots that broke out in July 1919 in Washington, DC, when Thurgood was eleven; for two nights white mobs roamed the streets of the city beating any blacks they encountered. Although the riots never made it to Baltimore, the violence shook Marshall’s sheltered worldview.

Adding to Marshall’s growing understanding of the realities of life in the segregated South was his family’s strong and committed opposition to Jim Crow. Marshall’s father, who with his light-skin and blue eyes could almost pass as white, was especially adamant that he be treated with respect regardless of his race. “He felt [racism] doubly,” Marshall recalled, “because he was blond and blue-eyed.… He could have passed for white, and a lot of times he would get into a big fight because someone would think he was white.” Willie Marshall, however, was a black man, and the contrast between how he could have been treated and how he actually was treated filled him with a deep, abiding anger. On one occasion, Willie

was working for a widow woman, very wealthy. One night, she decided to show off her little poodle, Nanky. “Nanky,” she said, “show the people which you would rather be, a nigger or dead.” The dog lay on its back with four feet up as if to say it would rather be dead. Pop walked right out the door and never went back.8

Willie expected his sons to do the same should they find themselves in a similar situation. One day, when Thurgood was about seven, he heard the word nigger and asked his father what it meant. Willie Marshall’s response was short, sharp, and to the point. “Anyone calls you a nigger, you not only got my permission to fight him—you got my orders to fight him.”9

Marshall had the opportunity to act on his f...