This is a test

- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Motivation, Ability and Confidence Building in People

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In order to get the best out of people in organisations, managers need to address the fundamental principals of people management: those of motivation, ability and confidence building. This proposed book aims to bring together clarity and understanding of these three main areas in one text with anecdotes and practical examples to enable managers to gain demonstrable improvements in organisational performance through their people. The material will be underpinned with just enough theory to establish a rationale for practice.

While a highly practical text, the aim is to meet many of the learning outcome requirements of the Certificate in Management and Diploma in Management people management / empowerment modules

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Motivation, Ability and Confidence Building in People by Adrian Mackay in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business generale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Part I Introduction

1 A Short History of Management

DOI: 10.4324/9780080885483-1

Managers learn in business school that relationships are either up or down, but the most important relationships today are sideways. If there is one thing that most of the people in management that I know have to learn is how to handle relationships where there is no authority and no orders.Professor Peter Drucker

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this chapter you will:

- Have had a brief overview of management theory as it has developed over the last century

- Understand the value of theory underpinning your practice

- Discover why so many ‘theories’ have had a shelf life

- Recognise the importance of motivation in the workplace

- Have had an introduction to some of the key influencers in management thinking.

Peter Drucker Did it First!

The challenge for management writers is finding things to say that Peter Drucker has not already said better. One just has to read a couple of his books for the first time – from the Concept of the Corporation (1946) to Management Challenges for the 21st Century (1999) – to realise that this is no exaggeration.

‘Drucker's primary contribution is not a single idea, but rather an entire body of work that has one gigantic advantage – nearly all if it is essentially right’ (Collins, 2004). While others wrote widely on management before Drucker (e.g. Taylor on efficiency or Follett on motivation), it was Drucker who first wove the threads into a coherent picture. In the foreword of The Practice of Management (1954), Jim Collins wrote, ‘This is the first book to look at management as a whole, the first that attempted to depict management as a distinct function, managing as specific work, and being a manager as a distinct responsibility’. Drucker proposed that limiting access to management jobs to ‘people with a special academic degree’ would be a mistake – anticipating by half a century both the rise in MBA programmes and the failure of management ‘theories’.

Professor Drucker explains, ‘Teaching 23-year-olds in an MBA programme strikes me largely as a waste of time. They lack the background of experience. You can teach them skills – accounting and what have you – but you cannot teach them management.’ Drucker's view is that management is neither an art nor a science but a practice – in which achievement is measured not by academic awards but by results.

The Practice of Management also had a piece of ‘modem wisdom’, that management is about innovation. ‘Every unit of the business should have clear responsibility and definite goals for innovation,’ he wrote – whether ‘selling or accounting, quality control or personnel management’. When people today speak of ‘business process innovation’, they are restating Drucker.

His early work warned of ‘the imaginative isolation of the executive’ – the tendency for managers to become so absorbed in their work that they become blind to emerging opportunities or threats. He feels that information technology has made matters much worse. ‘Executives are totally flooded with inside data to the exclusion of outside data.’

In Concept of the Corporation, he described in detail his ideas for ‘self-governing plant communities’ in which workers would play a central role in setting priorities and formulating policies. He considers his ‘… ideas for the self-governing plant community and for the responsible worker to be both the most important and the most original’, he wrote years later in his autobiography, Adventures of a Bystander. He feels that the labour movement stifled the self-governing plant community; by representing the workers the unions stopped every direct relationship between management and employees.

However, Drucker feels that the rise of the knowledge workers – a phrase he coined in The Age of Discontinuity (1969) – has changed the rules away from the shop-floor. Communities of practice reaching across boundaries are often stronger than bonds within a particular company. As he pointed out in Managing in Turbulent Times (1980), successful organisations must learn to think of themselves as orchestras, not armies. Today, he explained, a multinational is a network of alliances for manufacturing, distribution, technology and so on. Sometimes there is stock participation as an indication of commitment but not for control. These companies are held together by strategy and information, not ownership. ‘Managers learn in business school that relationships are either up or down, but the most important relationships today are sideways. If there is one thing that most of the people in management that I know have to learn it is how to handle relationships where there is no authority and no orders.’

Hence the need for managers to excel at relationships in which they have little authority and even less control. And that cannot be learnt in the lecture theatre or from a book.

So Why Bother Studying Management Theories?

The more extensive a man's knowledge of what has been done, the greater will be his power of knowing what to do.Benjamin Disraeli, British Prime Minister

We all have our preferred methods of learning (see Chapter 12) and many of us like to ‘try things out’ and discover the practical uses of a new ‘tool’. We may not much like the idea of sitting back, reflecting on our experiences and trying to put those experiences into a logical framework or theory.

Yet a theory may well help us better understand our experiences and help us better use the knowledge we have gained. Theory and practice support each other: theoretical knowledge can often give us a good base for developing our practical skills.

So, take time to reflect. Consider and relate the theories outlined in this book to your own practical experience. Experiment and see if the theory makes sense to you and helps your understanding of the subject. If, having done all of that, the theory does not help you, then identify the reasons why and put that theory aside. A theory is only useful if it helps you better understand and use your own knowledge.

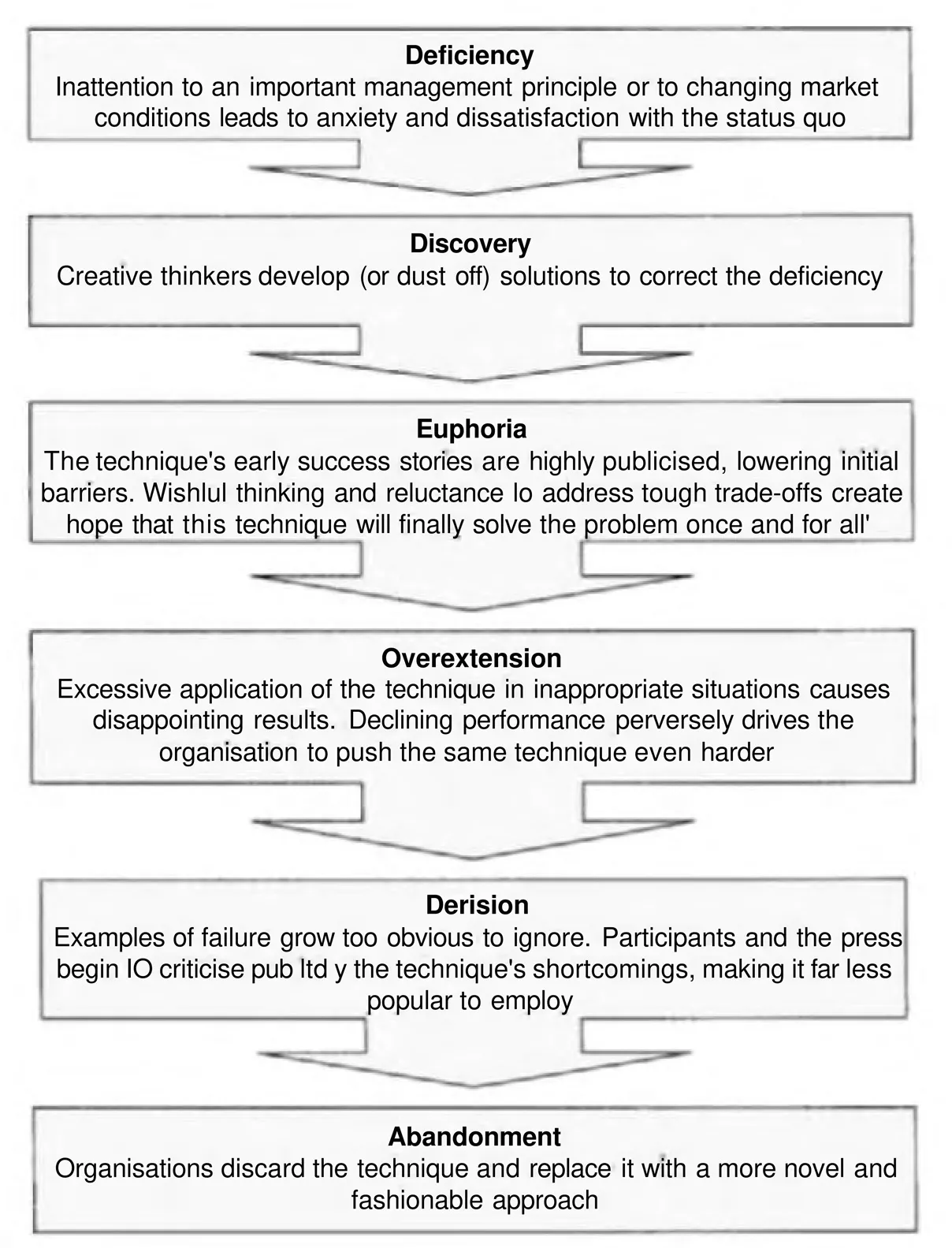

A theory that all management theories have a life cycle was published in America in 1993 in a magazine called Planning Review. It is believed that the theory originated in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Boston. It is outlined in Figure 1.1. The cause of the failure frequently lies in the stage of Overextension: organisations looking for the quick-fix flavour-of-the-month. As the originators imply: announce the new system; arrange some training courses; and then sit back and wait for the magic to work. If only business management were so simple!

Whenever we consider a theory, especially one that has been criticised or derided, we need to reflect on how much of the criticism is due to flaws in the original theory and how much is due to the theory being misapplied in practice.

One Hundred Years in the Making

Managers' beliefs about how to get the best out of people at work have changed as the 20th century has progressed. This section briefly outlines those changing beliefs and refers to a few of the many researchers who have influenced management thinking.

The approach in the opening years of the last century was very much in line with the views of Frederick Taylor – the father of scientific management – and other work study practitioners such as Gantt. They believed that jobs could be standardised and workers could produce more if they had the right rest breaks to reduce fatigue, the right tools for the job and the right monetary reward in terms of a piecework bonus. Such concepts are sometimes referred to as Rational-Economic models.

Given the situation of increasing industrial production and a largely unskilled and un-educated immigrant workforce in the USA, the scientific management approach did bring benefits. However, it took no account of workers as individual human beings.

With her concern for creative experience, democracy and for developing local community organisations, Mary Parker Follett is an often forgotten, but still deeply instructive, thinker for educators on motivation at the beginning of the 20th century.

By the late 1920s, Elton Mayo (usually acknowledged as the founder of Human Relations Management) was conducting research at the Hawthorne Works of Western Electric Co. in Chicago. The aim of his research was to find the relationship between the lighting of the work area and the productivity of a work group, where they found that a key factor in productivity improvement was the social relationships of the work group. This will be explored further in a later section.

Starting in the 1950s there was a growth in what was called behavioural science: attempts to define and explain the behaviour of individuals and groups. The concepts that were developed are sometimes referred to as self-actualising models.

In the mid-l950s, Frederick Herzberg produced what is often known as his Hygiene/Motivator theory. He defined certain factors linked to the job environment that cause dissatisfaction with a job: the Hygiene factors. These encompass things such as style of supervision, physical working conditions and pay. They must be right to avoid dissatisfaction, but increasing them above the appropriate level will not increase motivation.

The factors he refers to as Motivators, that encourage people to put extra effort into a job, are the ones inherent in the job itself: a sense of achievement, advancement, recognition and so on.

Another key researcher, Abraham Maslow, categorised people's needs into five primary classifications arranged in a hierarchy. Each level must be satisfied to some extent before the next becomes dominant. The basic needs are:

- Physiological: basic physical and biological needs

- Safety: physical and psychological security

- Social: love, affection and social relationships

- Esteem: self-respect, independence and prestige

- Self-realisation: self-fulfilment, accomplishment and personal identity.

It is these needs that act as internal motivators – both within and outside work.

Douglas McGregor showed how a leader's assumptions about other people dictate that leader's approach. He defined a set of assumptions called Theory X which stated that the average human being dislikes work and needs to be directed, coerced and controlled. Such assumptions result in an autocratic leadership style – which, in turn, results in the behaviour predicted by the Theory X assumptions! His alternative set of assumptions, which he labelled Theory Y, are about people being imaginative, responsible and able to exercise self-control. These assumptions lead to a more participative leadership style – and thus the behaviour predicted by the assumptions.

The Tannenbaum and Schmidt Continuum links in with McGregor's Theory X and Y and shows how a leader's style of decision-making can be authoritarian (Theory X) or may give subordinates a significant amount of freedom in making a decision (Theory Y).

The 1960s also saw a focus on the effects of different leadership styles. Rensis Likert...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- About the author

- Part I Introduction

- 1 A Short History of Management

- Part II Motivation Building

- 2 A Definition of Motivation

- 3 Are They Motivated?

- 4 Approaches to Motivation

- 5 Motivating Individuals

- 6 Motivating Teams

- 7 Effort, Performance and Reward

- 8 Selling the Vision

- 9 Mackay's Motivation Development Model

- Part III Ability Building

- 10 The Learning Organisation

- 11 Lifelong Learning and CPD

- 12 Individual Learning Styles

- 13 Management Style and Ability Development

- 14 Mackay's Ability Development Model

- Part IV Confidence Building

- 15 Self-esteem

- 16 Assertiveness

- 17 Achievement

- 18 Building Confidence Through Constructive Feedback

- 19 Mackay's Confidence Development Model

- Part V Looking Forward

- 20 Times aye Changing

- 21 The Future of Work

- Index