- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Environmental Management for Hotels

About this book

Environmental Management for Hotels is a textbook for hospitality students that covers the relatively new field of environmental management. The reader is guided in how to make decisions which allow hotels to obtain optimum benefits for the environment whilst not threatening their own financial viability.

Students are given an understanding of both the concepts and practical implications of environmental challenges relating to hotels. The case study material incorporated ties in theory with real life, and provides an international context. The text emphasizes supervisory issues which relate to the management of hospitality operations in ways which are sensitive to the impact on the environment. The main areas of environmental management featured are: *water *energy *the indoor environment *materials and waste.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Introduction

What do we Mean by ‘The Environment’?

While there are several different ways in which the word ‘environment’ is used, most people are aware that there is a need for all of us to take care of the environment, if we are not to threaten the ability of the earth to support future generations. Some aspects of the environment are very obvious from our day-to-day lives, such as increasing traffic levels, together with the associated air pollution and loss of greenbelt (protected areas of land surrounding towns and cities) and the countryside to road development and urbanization. We are aware of other dangers through the debate in the media, but these issues vary from tangible effects such as the shortage of physical resources (such as fossil fuels) to less evident and more long-term effects such as global warming and the hole in the ozone layer. The difficulty lies in translating these overall concerns, particularly those that are not directly related to us and which are less tangible, into action by the organization and by the individual. Our actions can sometimes seem inconsequential, compared to the size of global problems (Wright, 1992).

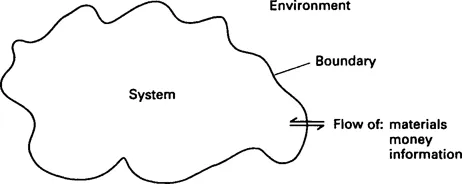

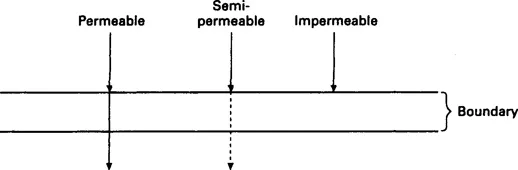

From a systems viewpoint, the term ‘the environment’ refers to any aspects that lie outside the system under consideration and which are separated from the system by a boundary (see Figure 1.1). The boundary acts as a control on the flows that take place from the system into the environment and vice versa. In this context we can consider the boundary to be a semi-permeable membrane which acts as a regulator, allowing the free flow of some things but preventing the flow of others (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.1 A system and its environment

Figure 1.2 Control of flows across a boundary

The boundary can be considered to be an artificial construct which allows us to define our area of interest. For example, we can think of our environment in terms of global, continental, national, regional, local and personal boundaries. In this way, systems form hierarchies. At one level, we can think of a person as a system, but then people working together in a hotel make up the human resource system. In a different context, these same people form the local and national social and political systems. Beyond this, individuals represent their national social and political groupings at international gatherings.

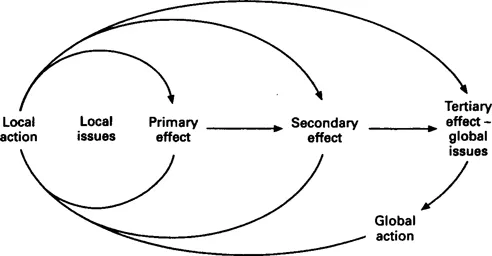

We can view some of the environmental issues, particularly the relationship between our actions and the environmental impacts in terms of primary, secondary and tertiary effects, as shown in Figure 1.3.At a local level, we might decide to scrap a number of old refrigerators which contain chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). We sell the old refrigerators to a local scrap metal merchant who crushes the refrigerators so that the metal can be sent to reprocessors, which results in CFCs being released into the atmosphere, but the amount of CFC is very small compared to the total emission of these gases. The release of CFCs is thought to contribute to the development of holes in the ozone layer, a secondary effect of the release of CFCs. These holes are thought to have a number of effects, such as causing an increase in cases of skin cancer caused by increased levels of ultra-violet radiation – a tertiary effect of the release of CFCs.

Figure 1.3 Think globally, act locally

Another example might be an increased use of electricity through the installation of air-conditioning, resulting in the need for more fossil fuel to be burned at a power station, causing increased emissions of carbon dioxide (CO,) and sulphur dioxide (SO,). These in turn cause acid rainfall over countryside at a great distance from the power station and the acid rain increases the acidity of lakes, killing the flora and fauna. We need to be able to make these links between local action and the secondary and tertiary global effects so that we can modify our local actions and halt some of these changes. If we are aware of these chains of cause and effect we can change our actions and convert some of these vicious circles of cause and effect into virtuous circles, where our actions minimize negative impacts and maximize positive ones.

Discussions take place, decisions are made and actions taken at global, national and local levels, and may result in a number of different outcomes, such as:

- International agreements

- National and international laws

- National/local policies

- National/local pressure groups

- Company policies and actions

- Individual actions.

Environmental problems must be tackled at all these levels. There is a clear need for global policy making and target setting, such as the Montreal Protocol of 1987, which established targets for CFC emissions. Another example might be the United Nations Rio Earth Summit Conference in 1992, at which a number of developed countries agreed that, by 2000, they would reduce the level of carbon dioxide emissions in their countries to the levels of 1990. The European Union has introduced several Directives which relate to the management of the environment. Within the LJK, there has been a long history of legislation related to the protection of the environment, including the Clean Air Act 1956 and the Control of Pollution Act 1974. Much of this early legislation was not directly related to the management of the environment in a holistic sense but was concerned with preventing gross pollution, largely related to health issues. However, as a response to the global issues of the Brundtland Report, the British government has produced a White Paper on the environment (HMSO, 1990).

Agreed policies by themselves will not necessarily cause people to change their habits. Action is required at a national and local level if any real changes are to result. Therefore we need to look at the possible driving forces to change at a local level, which are essential if any of these global issues are to be addressed.

The Driving Forces for Change

There are five main forces for change within an organization:

- Legislative and fiscal requirements

- Advantages resulting from financial savings

- Consumer attitudes

- Public opinion

- Enlightened management.

In relation to the last point, some companies recognize the importance to the company of its social and environmental responsibilities. Companies are now being measured not only on their financial performance but also on their ethical performance. This affects both shareholders and consumers and a number of investors take a great deal of interest in the broad range of ethical issues facing a company, including the environment. However, it is often difficult, particularly for the small organizations, to know how to respond to these issues and to generate the resources needed to do so.

Over recent years companies have become aware of the development of pressure groups and green politics. Steven Young, in his book on The Politics of the Environment, reviews the development of environmental pressure groups and green political parties (Young, 1993). Many of the early groups, going back to the Commons, Open Spaces and Footpaths Preservation Society (established in 1865), were concerned with the natural heritage together with the flora and fauna. Groups with a broader political agenda started much later with, for example, Friends of the Earth in 1971 and Greenpeace in 1977. From being very radical, many of these groups have now become a much more central part of pressure politics and operate through tactical alliances on specific issues. Green political parties started in the 1970s, partly as a result of many of the pressure groups such as Friends of the Earth. They achieved the greatest success in Europe, particularly in Germany and Switzerland. While green political parties have had mixed electoral success, they have had a distinct impact on more conventional political parties and governments.

Environmental awareness among consumers has increased, albeit from a low base until now most manufacturers have responded even if only in a minor way to these concerns and a number of manufacturers have developed specific eco-friendly products.

Sustainability and the Protection of Scarce Resources

Sustainabilty

One of the most fundamental principles of environmental management relates to the establishment of sustainable development. The Brundtland Report (World Commission on Environmental Development, 1987) defined sustainable development as 'development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs'. This can be viewed in a number of ways which relate to physical and social factors. In physical terms, there is a need to conserve scarce physical resources such as minerals and to minimize negative impacts on the physical environment through pollution. Any buildings or other form of built development needs to be sensitive to social, political, cultural and geographical aspects of the site chosen for development.

The concept of sustainable development has been expanded to cover seven key aspects (Young, 1993):

- Futurity: developments must be considered against a longer time-span than that normally used by businesses and politicians.

- Inter-generation equality: current activities should not deplete the resource base available to future generations, so that a constant resource capital can be passed on.

- Participation: all political and social groups affected by a development should be involved in debate and decision making.

- The balancing of economic and environmental factors: decisions should be made on the basis of a broader range of issues than the economic costs and environmental issues should be elevated from that of a constraint on development.

- Environmental capacities: all environmental impacts should be assessed in terms of their effect on equilibrium processes so that delicate ecological balances are not disturbed.

- Emphasis on quality as well as quantity: decisions should not be made on the basis of ‘least-cost’ but on a solution which gives the least damaging long-term solution.

- Compatibility with local ecosystems: to ensure that developments sustain local social, political, agricultural and ecological systems.

In reviewing the effect of a business on sustainability we can view its operations in terms of its inputs (the way in which it consumes resources) and its outputs (the negative and positive impacts on the environment).

Inputs: Renewable and Non-Renewable Resources

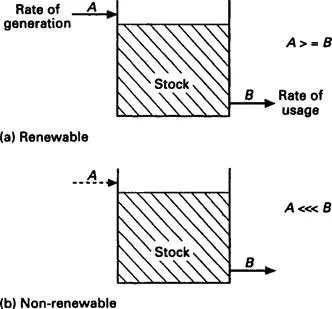

Although this is a simplification, it is possible to consider resources as either renewable or non-renewable. A non-renewable resource is one for which there is a finite supply which, once it has been used. up, cannot be replaced. The easiest way to think of this is that there is a store of the material from which we can draw supplies, thereby reducing the stock (see Figure 1.4). The amount of material remaining depends upon the rate of use. Examples of non-renewable resources are minerals such as copper and lead. Other examples include the fossil fuels. The fossil fuels are a good example; they resulted from the conversion of the energy of the sun into chemical energy, in the form of plant and animal tissues over many millions of years. Although, in principle, the conditions which led to the development of coal, gas and oil still exist in the world, the rate of extraction is so much greater than the rate of formation that they are, for all intents and purposes, non-renewable. It may be argued that, as materials become more expensive, there is a greater incentive to seek out and exploit new supplies. To some extent this is true, but all this does is to extend the life of the supply; it is still finite. In order to conserve supplies, the best approach is to reduce the rate of usage of these materials and to recover as much of the resource as possible after use.

Figure 1.4 Renewable and non-renewable resources

In contrast, renewable resources are constantly being replenished and the rate of use does not affect future availability. Very few resources are fully renewable under all conditions but a good example of one is solar energy. No matter how much solar energy we use for growing crops, heating buildings or generating electricity, this does not affect the rate of supply from the sun. However, solar energy is an exception and with most renewable materials we are concerned with maintaining the balance between the rate of production and the rate of use. If we use a resource at a higher rate than that at which it is being regenerated, then we start to consume stocks and the supply declines. The material is...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Environmental management

- 3. Water management

- 4. Energy management

- 5. Management of the indoor environment

- 6. Materials and waste management

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Environmental Management for Hotels by David Kirk in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Hospitality, Travel & Tourism Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.