This is a test

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Roles of the Northern Goddess

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

While much work has been done on goddesses of the ancient world and the male gods of pre-Christian Scandinavia, the northern goddesses have been largely neglected. Roles of the Northern Goddess presents a highly readable study of the worship of these goddesses by men and women. With its use of evidence from early literature, popular tradition, legend and archaeology, this book investigates the role of the early hunting goddess and the local goddesses who were involved in all aspects of the household and the farm. What emerges is that the goddess was both benevolent and destructive, a powerful figure closely concerned with birth and death and with destiny of individuals.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Roles of the Northern Goddess by Dr Hilda Ellis Davidson, Hilda Ellis Davidson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I

MISTRESS OF THE ANIMALS

THE RULER OF THE WILD

The inhabitants of north-western Europe were hunters for a vast period of time before they adopted a more settled way of life and took to herding domestic animals and cultivating the earth. Even after this, hunting continued to be of great importance, particularly in forested and mountainous regions; it was a way of obtaining food for the community, and a challenging and exciting occupation, involving great risks but promising considerable rewards. It would be surprising if the hunters did not seek supernatural help, and many think that the earliest goddess worshipped in the communities of the Palaeolithic Age was a hunting one. Where hunting is still necessary to supplement a way of life, for instance in parts of the Caucasus, it is possible to gain some idea of how such a goddess became established in myth and local legend.

Comparatively little work has been done in Britain on this subject, but Swedish, Finnish, Russian and German scholars have discussed the character of the hunting-goddess in considerable detail. She was regarded as the ruler of the forest and wild places, guarding and protecting the animals that dwell there. She allowed hunters to kill her creatures if they kept her rules and earned her favour, but if they offended her, she was a dangerous enemy, destroying them without mercy. Such a goddess might be in company with a male ruler of the wild, to whom the hunters also turned for assistance. It is hard to discover which came first; some think that the famous naked goddess of Laussel with her bison horn was a deity of this kind, linked with the moon, which must have been of great importance for the hunters. It was of primary importance also to women because of the relationship of the lunar calendar to menstruation and childbearing, and these two aspects appear to come together in the character of the early goddess (Marshack 1972: 335ff.).

At Çatal Hüyük in Anatolia, a town established as early as the seventh millennium BC, the symbolism in one of the shrines indicates that the female deity worshipped there not only was associated with birth and with grain (see p.), but also presided over hunting. At Level III, the ‘Hunting Shrine’ where hunting scenes were painted on the walls, a goddess with leopards appears beside hunters clothed in leopard skins, surrounding a stag or bull (Mellaart 1967: 182). Moreover the skulls of bulls are shown emerging from between the thighs of the goddess in other shrines, suggesting that she is the Mother of the Beasts hunted and sacrificed (Burkert 1983: 79). The Phrygian goddess Kybele ruled over wolves and lions and was associated with mountains, and she is thought to be the goddess depicted as giving birth at Çatal Hüyük (Vermaseren 1977: 9ff.).

Marija Gimbutas saw the Lady of the Beasts as one aspect of the Great Goddess, supreme in an early matriarchal society (Gimbutas 1982: 152, 197ff.), but it must be stressed that the hunting-goddess is found in many parts of the world, far beyond the confines of Old Europe as Gimbutas defined it. As Burkert points out, female dominance is unlikely in Upper Palaeolithic hunting societies (Burkert 1983: 80), while the hunting-goddess, worshipped primarily by men, showed hostility towards women.

The concept of a divine ruler of the wild, male or female, is thought by some to have evolved out of a belief in an animal soul, rather than from animistic beliefs in spirits inhabiting the world of nature, or Mannhardt’s ‘tree-soul’ imagined in animal or human form (Wikman 1961: 12). There may well be a link with the animal guardian spirit of the shaman, since shamanism is an inheritance from the ancient hunting culture, even though not found among all hunting peoples.

A tradition found among some hunters is that the slain animal will be reborn if its bones are preserved and certain rituals carried out (Friedrich 1941: 32). In three villages inhabited by the Minaro in a remote area of the Himalayas, Michael Peissel (1984: 41ff.) found that the people still worshipped male and female deities who were rulers of nature, whose help was needed when they hunted the ibex. There was a goddess Mu-shiring-men to whom a unicorn ibex with a golden horn belonged, whose rules must not be broken when hunting. When they killed an ibex, they etched out the figure of one on a rock, to cancel out their guilt in killing one of her animals, and this ensured that it would be restored to life (Peissel 1984: 41ff.).

The ruler of animals may be pictured in animal form, perhaps because early hunters observed that there was always a leading animal in the herd, just as there was a headman among the hunters (Hultkrantz 1961: 58–9). Among the Siberian tribes, an outstanding animal viewed by the hunter might be taken as the ‘master’ of his kind, although sometimes this ‘master’ was pictured as a monstrous creature, or as half-animal and half-human (Lot-Falck 1953: 63– 4). In the case of a goddess who guarded certain animals, she might teach the hunters skills and give them directions where to find game. Taboos and rituals imposed by her had to be faithfully observed, and in the Caucasus the goddesses were far stricter over this than the male supernatural rulers of forest or mountain (Chaudhri 1996: 169).

It is usually the economically valuable animals that are said to possess guardians of this kind. In Europe in early times the most important was the bear; a bear cult extended across Europe and Asia to Japan, where Ainu ritual and sacrifice continued into the twentieth century. Deer were also of primary importance in many areas of Europe; the goddess was often said to herd and milk them, and might appear in the form of a white hind.

Hunting is primarily a male occupation, although Briffault (1927: 446ff.) found some communities where women were skilled hunters and responsible for the fishing. There is ample evidence for a goddess worshipped by the male hunters, who made offerings to her and respected and feared her power. In many warrior societies youths were trained as hunters; there is the same need for male co-operation in communal hunts as in the organization of war parties, and the same types of weapon were used (Feest 1980: 17). Thus young men could come directly under the influence of the goddess but, as in the case of the Greek Artemis (see pp.), she could also preside over the training of young girls.

The memory of a hunting-goddess, mistress of the wild creatures, still survives in the Caucasus, where deer and mountain goats are hunted (Chaudhri 1996). Among the Ossetes the main hunting deity was the male Æfsati, on whose goodwill the success of the hunt depended; he was pictured as old and bearded and sometimes blind or one-eyed, with beautiful daughters who according to legend were sometimes allowed to marry poor huntsmen. Similar male divinities were regarded as patrons of the hunt and rulers of the animals among other Caucasian peoples, but there were also hunting-goddesses.

One of these was the goddess Dali, held in mountainous regions of Georgia to be responsible for the hoofed and horned animals, while birds and fishes, wolves, bears and foxes came under the rule of male gods. In surviving tales and poems about her relationship with the hunters, Dali is generally described as young and beautiful, with wonderful long hair, either black or golden, but she nevertheless inspired terror in those who encountered her. She sometimes took on the form of one of her animals, perhaps a pure white hind or an animal with a golden horn, and would tend and milk her flock. She might accept a hunter as her lover, but this meant that he could have no sexual relations with mortal women hereafter, and the affair might well lead to his death,

Again in a remote part of Japan, where particular groups known as matagi continue to hunt bears in the mountains, there are vigorous traditions still surviving concerning the goddess Yamanokami, a powerful deity with no male associates (Blacker 1996). Here as in the Caucasus the goddess is a beautiful and erotic figure, but capable of changing into a monstrous and destructive one, ready to kill those who offend her. There were strict rules concerning the hunters’ wives, and all women were excluded from the hunting ground; no articles associated with them might be taken there, nor any woman’s name mentioned. Men had to refrain from sexual intercourse before a hunt, and women might find it prudent to stay indoors on Yamanokami’s festival. Such surviving traditions about the hunting-goddess help us to understand the earlier concept of a merciless and destructive goddess, with bountiful gifts for those she favoured, but whose continued favour could never be relied upon.

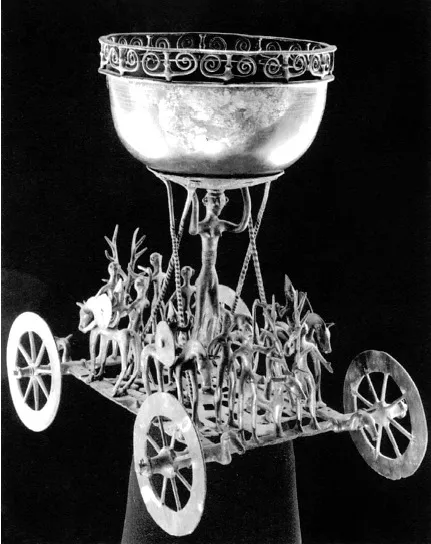

A possible representation of an early European goddess of this type associated with the stag is on a wagon found in a cremation grave of the seventh century BC in Strettweg in Austria (Megaw 1970: 59). Also in the grave were several metal vessels, an axe, a spear and three horse-bits, suggesting that the dead was a warrior or a hunter. The wagon (Plate 2) is a bronze platform on wheels, 240 mm long, holding a group of figures thought to be the work of a Greek craftsman (Sandars 1968: 215). The central figure, towering high above the rest, is a female one, wearing earrings, and carrying a wide, shallow bowl on her head, beneath which she wears a protective pad of a type still in use in countries where women bear burdens in this way. A pair of mounted warriors are placed before and behind her, facing away from her; in between one pair is a woman, and in between the other an ithyphallic man brandishing an axe. At the front of each group is a fine stag with antlers, flanked on either side by a youthful figure which might be of either sex; these have their hands on the stag’s antlers. The central figure wears a belt while the rest are naked. The link between a possible goddess and the stag on what appears to be a cult object suggests that this group was concerned with the worship of the Mistress of the Wild associated with the wild deer hunted in the forest.

In Ancient Greece, Artemis was worshipped as a goddess of this kind, separate in nature from the goddess of the grain. Like Yamanokami (Blacker 1996: 178) she ruled the wild countryside, outside the settled communities and cultivated land, and may be seen as a goddess of the boundary area between tamed and untamed, a divinity of the margins (Vernant 1987: 420). She was also the guardian of children and unruly adolescents, until they were ready to return to the city and adult life (Ellinger 1991: 445–6). Young men training to be warriors came under her sway, and she imposed rigid rules against undue savagery and destructive slaughter in warfare as well as hunting, although she cannot be regarded as a war goddess. She had many local names, and the Romans worshipped her as Diana; she was followed by nymphs who aided her in her hunting, and were forbidden to have sexual relations with men. She might appear as either a bear or a hind, and according to Pausanias her temple in Arcadia contained her statue wrapped in a deer pelt. Strabo refers to her sacred island to which the does swam when the time came for them to give birth; she is a typical hunting-goddess in the protection given to young animals.

Although an unmarried goddess, Artemis helped women in childbirth, while her protection extended over young girls from birth until they themselves became mothers (see p.). Athenian girls of good family danced as bears, ‘playing the She-bear’ at the Brauronia, the festival at her shrine in Athens; while those who took part in a retreat there in preparation for marriage were known as arktoi (Borgeaud 1988: 32). Lilli Kahil (1977) has analysed scenes on fragments of bowls in which little girls and some aged about 12 or 13 are taking part in rites which involve the figure of a bear, representations of Apollo and Artemis, and a priest and priestess wearing bear masks. She believes that these represent the initation rite at the sanctuary of Artemis, and that the older girls, who are running naked, are those who had reached puberty. In his illuminating study of myths about the hunter and the huntress, Fontenrose (1981) has shown how the concept of a hunting-goddess was deeply established among Greek writers. She was followed by a troop of young women pledged to chastity, who would be punished, and possibly killed, if they became pregnant. She regularly accepted hunters as lovers, but such relationships often ended in death. The best known legend is that of Aktaion, torn to pieces by his own hounds, when the goddess either turned him into a stag, threw a stag pelt over him, or shot him with her bow (Fontenrose 1981: 33ff.).

Plate 2 Model of cult-wagon in bronze, from Strettweg, Austria, with figure of goddess in centre surrounded by smaller figures, including two stags. Ht 22.6 cm. Courtesy Stiermarkisches Landesmuseum Joanneum, Bild und Tonnarchiv, Graz.

While some men met their deaths as a result of offending Artemis, she was held responsible for the slaying of a large number of women (see p.). Not only unchaste maidens in her service but also apparently blameless women were said to be shot by an arrow from her bow, according to references to her in the Iliad and the Odyssey (Ganz 1993: 97ff.). Penelope for instance in her unhappiness wishes that holy Artemis would grant her death instantly and save her from a life of anguish (Odyssey 18: 202), while Odysseus asks his dead mother whether Artemis the Archeress had visited her and killed her ‘with her gentle darts’ (Odyssey 11: 171–3). Artemis probably came into Greece from Anatolia about the sixth century BC, and was closely related to Kybele, but may have merged with Greek hunting-goddesses of similar character.

A Latin spell to Artemis on a copper nail (Grambø 1964: 45) attributes to the goddess the power to bind her hounds and prevent them from attacking the domestic animals. Her hounds were predatory animals of the wilds, such as wolves, which may also be called her herds, and this picture of a goddess restraining or releasing the wild animals at will has been retained in later folklore of northern Europe (see pp.). The prayer runs as follows:

O Lady Artemis, do not loosen your golden chains. See your hounds of plain or forest, white or coloured, let them not with open jaws seek out the fields of the plain, let them come empty and let them go empty. Make them run off, and let them not come to our farm, nor touch our cattle nor harm our donkeys. In the name of God, in the name of Solomon, and in the name of the Lady Artemis.

(Grambø’s translation)

Hunting dogs are shown on the bowls from the sanctuary of Artemis already mentioned, and dogs are frequently associated with later hunting-goddesses, such as the goddess Dali in the Caucasus. Important too is the weapon which the goddess carries. Artemis has a golden bow, and Callimachus describes how just after her birth she was given her dogs by the shepherd-god Pan:

To you the bearded one gave two half-black dogs, three with spotted ears, and one spotted all over, who could pull down even lions, when they clutched their throats and dragged them still alive to the camp. He gave several others, seven bitches of Cynosuria, swifter than the wind, none quicker to pursue deer and the unblinking hare, quick also to signal the bed of the deer, and the burrow of the porcupine, and to lead us along the track of the gazelle.

(Borgeaud 1988: 63)

Direct evidence for a hunting-goddess in the Roman Empire is less easy to find, although Diana took over the attributes of Artemis. There are, however, several examples of a male hunting-god, armed for the hunt and perhaps carrying game, yet at the same time displaying protectiveness and even affection towards his quarry. Miranda Green in Symbol and Image in Celtic Religious Art (1989: 102) shows a male figure from a sanctuary in a mountainous region of the Donon, carrying a bag which holds the fruits of the forest, pine-cone, acorns and nuts. He wears a wolfskin and carries a hunting knife and a curved chopper, with a lance at his side, and rests his hand on the antlers of a stag which stands close to him, apparently unafraid. Arrian in Cynegetica (XIV) refers to the Celts seeking the blessing of the gods before going hunting, and refers to a hunting-goddess to whom the sacrifice of a domestic animal was made, together with the first-fruits of the hunt, while Diodorus Siculus (V: 29) alludes to the practice of nailing up part of the first animal taken ‘in certain kinds of hunting’ (M. J. Green 1992: 62).

Another possible representation of...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- PLATES

- FIGURES

- INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER I: MISTRESS OF THE ANIMALS

- CHAPTER II: MISTRESS OF THE GRAIN

- CHAPTER III: MISTRESS OF DISTAFF AND LOOM

- CHAPTER IV: MISTRESS OF THE HOUSEHOLD

- CHAPTER V: MISTRESS OF LIFE AND DEATH

- CONCLUSION

- BIBLIOGRAPHY