This is a test

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

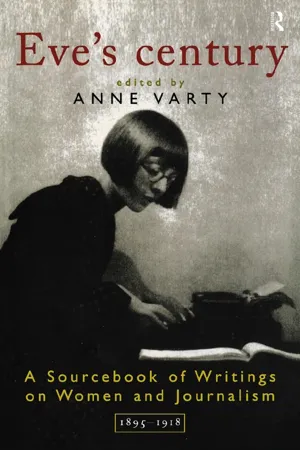

This unique collection of extracts is taken from women's journals and magazines - both British and American - on the eve of the twentieth century. Arranged by subject, the collection focuses on what this pivotal moment represented for women and includes an introduction to women's journalism of the period.

The rapidly changing conditions then surrounding a woman's world are illustrated here by sections on:

* monarchy

* women and war

* colonial women

* the politics of emancipation

* and girlhood.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Eve's Century by Anne Varty in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Collections. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE NEW CENTURY

In January 1900 controversy about whether the twentieth century had begun raged throughout the world press. Laborious counting exercises were rehearsed, and it was finally agreed across Britain and America that the moment of transition was at midnight on 31 December 1900. Only the German Kaiser celebrated the start of the twentieth century on 1 January 1900. There was discussion too about the international date-line, and John Ritchie explains to readers of the Ladies’ Home Journal in January 1900 the precise latitude and longitude of this, and where, consequently, the sun would first rise in the twentieth century. He notes how stories of political struggle are inscribed in the calendar. Consensus about the status of women at this time was just as unstable, and no less driven by ideology, as that about dates and places. Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s typically reformist article from the North American Review (a journal for general readership) of December 1900 is the last word in a debate which began the previous month with a profoundly reactionary piece by Flora McDonald Thompson, ‘Retrogression of the American Woman’. Thompson is appalled by the degeneracy of her contemporaries, and takes as the cornerstone of her argument what De Tocqueville wrote about American women in Democracy.

No free communities ever existed without morals; and as I have observed, morals are the work of woman. Consequently, whatever affects the condition of women, their habits and their opinions, has great political importance in my eyes.(North American Review, November 1900, p. 749)

Thompson accuses her contemporary women of moral corruption, of too much divorce, of striving for economic and political independence, and of eroding the traditional structure of family life and values. She claims that the Americans are now no better than the Europeans whom De Tocqueville accused of ‘confounding together the different characteristics of the sexes, [to] make of man and woman beings not only equal but alike’ (ibid. p. 759). Elizabeth Cady Stanton fights off these arguments in the course of putting forward her own fresher vision.Stanton’s piece is one of many which appeared at this time. For example, two articles appeared in the Temple Magazine (for general readership but catering largely for women); the first, by Lady Violet Greville, ‘Woman and the New Century’ in August 1901, gave an account of educational and professional opportunities made available to women in the course of the nineteenth century. She asks ‘are women happier, better, more healthy for all this storm and stress, this endless business and worry?’ (p. 949). Its companion piece, ‘Woman at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century,’ by Mrs Hirst Alexander in the November issue of 1901, gives detailed information about career and social prospects open to women. These are framed by an expression of conventional piety: ‘Women are awakening everywhere to the high work lying to their hands in the near future . . . work that shall be an instrument, under God’s guidance, in His own divine evolution of eternal order out of original chaos. . . .’ (p. 95).It was not just material for Sunday reading which struck a note of piety on heralding the twentieth century. A poem, ‘The New Age’, by Sir Lewis Morris from the Gentlewoman on 5 January 1901 sounded in similar tones:

Bring Thou the full enfranchisement which can

Make of the Woman a new precious Force,

The Partner, not the Parasite, of Man,

A strong stream welling from a purer source.

Make of the Woman a new precious Force,

The Partner, not the Parasite, of Man,

A strong stream welling from a purer source.

Then shall the World’s long agony give place

To gentler aims which seek the better part,

Peace, Mercy, Purity, abounding Grace,

Born of the wedded powers of Mind and Heart.

To gentler aims which seek the better part,

Peace, Mercy, Purity, abounding Grace,

Born of the wedded powers of Mind and Heart.

A purer life, a higher Destiny,

A nobler Art, a deeper love of Right;

Rise, Woman, fit thyself for what shall be,

Ascend, soar upward in the new-born Light.

A nobler Art, a deeper love of Right;

Rise, Woman, fit thyself for what shall be,

Ascend, soar upward in the new-born Light.

Wit rather than sentiment was to be found in the competition pages. The Gentlewoman announced competition winners for epigrammatic definitions of the new century on 12 January 1901. The winning entry was ‘the title page to a sealed book’, while runners up included: ‘The last century in the score. A new starter for the 2000 (Two Thousand)’; ‘The future of the past’; ‘The latest thing in cycles, with great improvements in the running’; ‘A new cycle on an old track.Time on a new cycle’; ‘The infant prodigy of Progressive parents’; ‘Preface to the Descent of Man’.

‘The So-Called Twentieth Century,’ editorial, Queen, The Lady’s Newspaper (London), 6 January 1900, p. 2

The Question as to whether we are or are not now in the twentieth century of the Christian era is one which is at the present time exercising many minds and exciting in some quarters much acrimonious discussion. Mere academical questions which are not capable of any very definite solution are precisely those on which disputants are apt to differ most strongly, and the subject under discussion is one of these.

In the first place, the data on which to argue are most unsatisfactory. The commonly accepted Christian era was not definitely fixed until the sixth century, and then it is well known that its founders were four or five years wrong in the date they assumed as that of its commencement. Then, again, comes the question as to whether they began with the year 0 or the year 1.

A century cannot possibly be completed until a hundred years have been completed, and the year 1900 is only the last year of the nineteenth century, which cannot terminate until the year is complete, consequently the twentieth century will begin at midnight on Dec. 31, 1900. It cannot possibly be otherwise unless we begin with the year nothing or 0, but no one believes in such a year or uses such an expression. We write of the years of the Christian era as AD1, or AD 1844, but never of AD 0. In the same manner, if we are writing of the years antecedent to the Christian era we never write or speak of BC 0, or of BC nothing; the idea is too absurd to be reasoned about.

Again, let us argue from the precisely parallel case of the age of children. When is a boy ten years old? Or, in other words, when has he completed his first decade? Obviously on his tenth birthday. But those who maintain that the twentieth century has now begun must, to be consistent, maintain that the boy is in his teens on his ninth birthday, if they maintain that the twentieth century begins with 1900. No mother regards her child as a year old on the day of its birth. She has to wait until the first year of its life is complete before making such an announcement, and she has to wait until ten years are completed before she can say her boy is now ten; and in the same manner we must all wait until the nineteenth century is complete before we can say we are in the twentieth. Again, illustrations may be taken from tangible objects. If a sum of one pound is to be paid in separate shillings, the debt will not be liquidated until the creditor has received twenty shillings; he will not allow the debtor to stop short with nineteen. This transformed into centuries is what those who maintain the twentieth century has begun are wishing us to receive. It is quite true that the 1900th year of the Christian era has commenced, but it must be concluded before the nineteenth century is finished, and then, and not before, shall we enter upon the twentieth century. . . .

But the anniversary of the penultimate Christmastide, the last one of the nineteenth century, has come and gone. The almost forgotten Christmas day of the olden time, namely, Twelfth Day, will soon have passed away. The New Year, which must be regarded as the last of the present century, is in progress, and we can but wish its termination to be brighter than its commencement, and that the Christmas immediately antecedent to the twentieth century may be characterised by the recurrence of the “Peace on earth and goodwill to all men,” a hope that we trust all our readers will live to see fulfilled.

‘Where the New Century Will Really Begin,’ John Ritchie, Jr., Ladies’ Home Journal (Philadelphia), January 1900, p. 7

There is a good deal of sentimental interest attaching to the opening of a new century. Which land will see it first? Whose eye will be the first to note its advent? Whose hail will usher in its earliest moment? Like so many of the phenomena, such as the eclipse and the transit of the planets, the incoming of the twentieth century will be in a region so sparsely settled as to be almost devoid of human life.

The first moment of the twentieth century, the first second of January 1, 1901, will occur in the midst of the Pacific Ocean, along a line conforming in general to the meridian of one hundred and eighty degrees east and west longitude from Greenwich. There is here no land of consequence to salute the new century; no human eye, save, perchance, that of the watch on board some tiny ship, will be there to see its entrance, and its only welcome will be, perhaps, the last strokes of the eight bells marking midnight on board some steamship or vessel which, by chance, may cross the meridian at that instant.

The first people to live in the twentieth century will be the Friendly Islanders, for the date-line, as it may be called, lies in the Pacific Ocean just to the east of their group. At that time, although it will be already Tuesday to them, all the rest of the world will be enjoying some phase of Monday, and the last day of the nineteenth century. At Melbourne the people will be going to bed, for it will be nearly ten o’clock; at Manila it will be two hours earlier in the evening; at Calcutta the English residents will be sitting at their Monday afternoon dinner, for it will be about six o’clock; and in London, “Big Ben,” in the tower of the House of Commons, will be striking the hour of noon. In Boston, New York and Washington half the people will be eating breakfast on Monday morning, while Chicago will be barely conscious of the dawn. At the same moment San Francisco will be in the deepest sleep of what is popularly called Sunday night, though really the early, dark hours of Monday morning, and half the Pacific will be wrapped in the darkness of the same morning hours, which become earlier to the west, until at Midway or Brooks Islands it will be but a few minutes past midnight of Sunday night. . . .

The Spaniards going west from their possessions in America carried their day to the Philippine Islands. The Dutch sailing east took their day with them to the adjacent islands of Borneo, Sumatra and Java, and to China. The circuit of the earth having thus been completed, there was the difference of a day between Manila and its neighbours, Manila being behind. As the business interests of the different islands brought them into closer relationships the absurdity of having different day-names in places so close together was the more striking. Accordingly, about the middle of the century the authorities arranged for a unification of dates, and a day was skipped by the Filipinos, the day being December 31, 1844. They went to bed on the evening of December 30, 1844, and awoke the next morning on January 1, 1845.

‘Progress of the American Woman,’ Elizabeth Cady Stanton, North American Review (New York), December 1900, pp. 905–7

An article, by Flora McDonald Thompson, entitled ‘Retrogression of the American Woman,’ which was published in the November number of the REVIEW, contains many startling assertions, which, if true, would be the despair of philosophers. The title itself contradicts the facts of the last half century.

When machinery entered the home, to relieve woman’s hands of the multiplicity of her labors, a new walk in life became inevitable for her. When our grandmothers made butter and cheese, dipped candles, dried and preserved fruits and vegetables, spun yarn, knit stockings, wove the family clothing, did all the mending of garments, the laundry work, cooking, patchwork and quilting, planting and weeding of gardens, and all the house-cleaning, they were fully occupied. But when, in course of time, all this was done by machinery, their hands were empty, and they were driven outside the home for occupation. If every woman had been sure of a strong right arm on which to lean until safe “on the other side of Jordan,”she might have rested, content to do nothing but bask in the smiles of her husband, and recite Mother Goose melodies to her children.

On that theory of woman’s position, men gradually took possession of all her employments. They are now the cooks on ocean steamers, on railroads, in all hotels, in fashionable homes and places of resort; they are at the head of laundries, bakeries and mercantile establishments, where tailor-made suits and hats are manufactured for women. Thus, women have been compelled to enter the factories, trades and professions, to provide their own clothes, food and shelter; and, to prepare themselves for the emergencies of life, they have made their way into the schools and colleges, the hospitals, courts, pulpits, editorial chairs, and they are at work throughout the whole field of literature, art, science and government. We should hardly say that the condition of an intelligent human being was retrogressive, in teaching mathematics instead of making marmalade; in instructing others in philosophy, instead of making pumpkin pie; in studying art, instead of drying apples. When hundreds of girls are graduating from our colleges with high honours every year, when they are interested in all the reforms of their day and generation, super-intending kindergarten schools, labouring to secure more merciful treatment for criminals in all our jails and prisons, better sanitary conditions for our homes, streets and public buildings, the abolition of the gallows and whipping-post, the settlement of all national disputes by arbitration instead of war, we must admit that woman’s moral influence is greater then it has ever been before at any time in the course of human development. Her moral power, in working side by side with man, is greatly to the advantage of both, as the co-education of the sexes has abundantly proved. When the sexes reach a perfect equilibrium we shall have higher conditions in the state, the church, and the home.

Matthew Arnold says: ‘The first desire of every cultivated mind is to take part in the great work of government.’ That woman now makes this demand is a crowning evidence of her higher development. For a true civilization, the masculine and feminine elements in humanity must be in exact equilibrium, just as the centripetal and centrifugal forces are in the material world. If it were possible to suspend either of these great forces for five minutes, we should have material chaos, – just what we have in the moral world to-day, because of the undue depression of the feminine element.

Tennyson, with prophetic vision, forecasts the true relations between man and woman in all the walks of life. He says:

Everywhere

Two heads in council, two beside the hearth,

Two in the tangled business of the world.

Two plummets dropped for one to sound the abyss

Of science and the secrets of the mind.

Two heads in council, two beside the hearth,

Two in the tangled business of the world.

Two plummets dropped for one to sound the abyss

Of science and the secrets of the mind.

The first step to be taken in the effort to elevate home life is to make provision for the broadest possible education of woman. Mrs Thompson attributes the increasing number of divorces to the moral degeneracy of woman; whereas it is the result of higher moral perceptions as to the mother’s responsibilities to the race. Woman has not heard in vain the warning voice of the prophets, ringing down through the centuries: ‘The sins of the father shall be visited upon the children unto the third and fourth generations.’ The more woman appreciates the influences in prenatal life, her power in moulding the race, and the necessity for a pure, exalted fatherhood, the more divorces we shall have, until girls enter this relation with greater care and wisdom. When Naquet’s divorce bill passed the French Chamber of Deputies, there were three thousand divorces asked for the first year, and most of the applicants were women. The majority of divorces in this country are also applied for by women. The higher intelligence woman has learned the causes that produce idiots, lunatics, criminals, degenerates of all kinds and degrees, and she is no longer a willing partner to the perpetuation of disgrace and misery.

The writer of the article on the ‘Retrogression of the American Woman’ makes one very puzzling assertion, that the present superiority of the sex immortalizes woman, but demoralizes man. Does she mean that a liberal education can only be acquired at the expense of one’s morals? ‘The American woman to-day,’ says the writer, ‘appears to be the fatal symptom of a mortally sick nation.’ This is a very pessimistic view to take of our Republic, with its government, religion, and social life, and its people in the full enjoyment of a degree of liberty never known in any nation before! In spite of this alleged wholesale demoralization of man, we have great statesmen, bishops, judges, philosophers, scientists, artists, authors, orators and inventors, who surprise us with new discoveries day by day, giving the mothers of the Republic abundant reason to be proud of their sons.

Virtue and subjection, with this writer, seem to be synonymous terms. Did our grandmother at the spinning wheel occupy a higher position in the scale of being than Maria Mitchell, Professor of Astronomy at Vassar College? Did the farmer’s wife at the washtub do a greater work for our country than the Widow Green, who invented the cotton-gin? Could Margaret Fuller, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Frances E. Willard, Mary Lyon, Clara Barton have done a better work churning butter or weeding their onion beds on their respective farms than the grand work they did in literature, education and reform? Could Fannie Kemble, Ellen Tree, Charlotte Cushman or Ellen Terry (if we may mention English as well as American women) have contributed more to the pleasure of their day and generation had they spent their lives at the spinning-wheel? No! Progress is the law, and the higher development of woman is one of the important steps that have been achieved.

There are great moral laws as fixed and universal as the laws of the material development going on all along the line, bringing the nations of the earth to a high point of civilization. True, as the nations rise and fall, their great works seem scattered to the winds. For example, Greek art, it is said, has never been equalled, but we would not change our ideas of human liberty, our comforts and conveniences in life, our wonderful inventions and scientific discoveries, the telegraph, the telephone, our modes of travel by sea, land and in the air, the general education and demand for better conditions and higher wages by the laboring masses, the abolition of slavery, rapid improvement in woman’s condition, the emancipation of large classes from the religious superstitions of the past, for all the wonderful productions of beauty at the very highest period of Greek art. In place of witchcraft, astrology and fortune-telling, we now have phrenology, astronomy and physiology; instead of famine, leprosy and plague, we owe to medical science a knowledge of sanitary laws; instead of an angry God, punishing us for our sins, we know that the evils that surround us are the result of our own ignorance of Nature’s laws. He who denies that progress is the law, in both the moral and material world, must be blind to the facts of history, and to what is passing before his eyes in his own day and generation.

The moral status of woman depends on her personal independence and capacity for self-support. ‘Give a man a right over my subsistence,’ says Alexander Hamilton, ‘and he holds a power over my whole moral being.’

De Tocqueville cannot be impressed into the service of the writer, nor fairly quoted, even inferentially, as saying that the moral status of the American woman in 1848, owing to certain causes at work, was higher than it would be in 1900. Progress is in the law, and woman, the greatest factor in civilization, must lead the van. Whatever degrades man of necessity degrades woman; whatever elevates woman of necessity elevates man.

‘The Two Centuries and This Magazine,’ Edward Bok, Ladies’ Home Journal (Philadelphia), January 1901, p. 16

This magazine and the nineteenth century...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrati-ons

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 The New Century

- 2 Futures

- 3 Retrospects

- 4 Politics

- 5 Colonials

- 6 War

- 7 Girls

- 8 Christmas

- 9 Advertising

- 10 Reference

- Selected Biographies

- Selected Further Reading