![]()

1

The Digital Intermediate Paradigm

The phrases “never been done before,” “pushing the envelope,” and “attempting the impossible” crop up rather often in the film industry, particularly in post-production. But the methodology used to finish HBO’s “Band of Brothers” mini-series in 2000 involved a completely new work flow, justifying the frequent use of these comments to some extent. Every scene of the production was shot on 35mm photographic film (with the exception of a number of computer-generated visual effects and a few seconds of 16mm footage), but by the time of completion, the entire, edited series existed only as a bunch of data stored on a number of hard disks and digital tapes. This wasn’t anything new in itself. Disney’s Toy Story had been an entirely digital production, and the film Pleasantville involved scanning and digitally color-grading a cut film to a set of digital files, before recording back onto film.

What was unique was the unprecedented level of control made available to the filmmakers. The series’ editors, who were themselves working with separate video references of all the film footage, were able to make adjustments to their cuts, and see the changes implemented into the final version almost instantly, the existing sequences rearranged, and any new material added. At the same time, the cinematographers and directors would oversee the color correction of the production interactively, at the highest possible level of quality, complete with visual effects and titles, and synchronized to the latest audio mix. They had the ability to jump to any particular scene and even to compare the look of multiple scenes to ensure continuity. Further, the level of control of color grading enabled a unique look that would be extremely difficult to obtain (some might say impossible) using traditional photochemical processes. Meanwhile, other departments composited titles, dissolves, and other optical effects with a similar degree of interactivity and control, and others used digital paint tools to remove defects such as dust and scratches from the scanned images, resulting in images of extremely high quality.

This process wasn’t completely smooth-running: a lot of things didn’t work as theorized, a great many things broke completely, and some days it seemed that we were attempting the impossible. But many lessons are learned the hard way, and envisioned ideals soon gave way to practical fixes and workarounds. And to some degree, that philosophy still prevails throughout this rapidly growing digital intermediate industry.

For this reason, the aim of this book is not just to present a technical discussion of the theoretical possibilities, the “wouldn’t it be good if everyone did approach”; the aim is also to cover current working practices, and explain why certain things have to be done the way they are—even though it can seem inefficient or irrational at times—and, of course, to list possible methods to improve them.

There is also a website that accompanies the book, which details new advances and changes in the industry, as well as points to other helpful resources. Find it online at www.digitalintermediates.org.

1.1 What is a Digital Intermediate?

If you have ever worked with an image-editing system, such as Adobe’s ubiquitous Photoshop (www.adobe.com), then you are already familiar with the concept of a digital intermediate. With digital image editing, you take an image from some source, such as a piece of film, a paper printout, or even an existing digital image (if using a digital camera for instance), bring it into your digital system (by using a scanner or by copying the file), make changes to it as required, and then output it (e.g., by printing onto photographic paper or putting it on the Internet). Your image has just undergone a digital intermediate process, one that is in very many ways analogous to the process used for high-budget feature films (albeit on a much smaller scale).

The digital intermediate is often defined as a digital replacement for a photochemical “intermediate”—a stage in processing in which a strip of film (either an “interpositive” or an “internegative”) is used to reorganize and make changes to the original, source footage prior to output—and is often regarded as only applicable to Hollywoodbudget film productions. It is true that the digital intermediate fulfills this function; however, it potentially fulfills many others too. First, any material that can be digitized (i.e., made digital) can be used as source material, and the same is also true of output format. For this reason, it is somewhat arrogant to presume that digital intermediates are only used for film production, as the digital intermediate paradigm has already been used with video production for many years. Second, the budget is something of a nonissue. More is possible with a larger budget, less compromises need to be made, and a higher level of quality can be maintained. But footage that is captured using consumer-grade DV camcorders as opposed to 35mm film cameras is still a candidate for a digital intermediate process. Possibly one of the most interesting features of the digital intermediate process is that it can be used for almost any budget or scale. So, perhaps for a better definition of what a digital intermediate is, it’s a paradigm for completing a production by digital means, whether it’s the latest Hollywood epic or an amateur wedding video.

1.2 Digital Intermediates for Video

Video editing used to be a fairly straightforward process, requiring two video cassette recorders (VCRs), one acting as a player, the other as a recorder. Shots are assembled onto the recorded tape by playing them in the desired sequence. This simple, yet efficient “tape-to-tape” system was excellent for putting programs together quickly, but it limited creativity and experimentation because you couldn’t go back and change something at the beginning without re-recording everything again. Video editing was a linear process (unlike film editing, where editors could happily chop up bits of film at the beginning of a reel without having to rework the whole film).

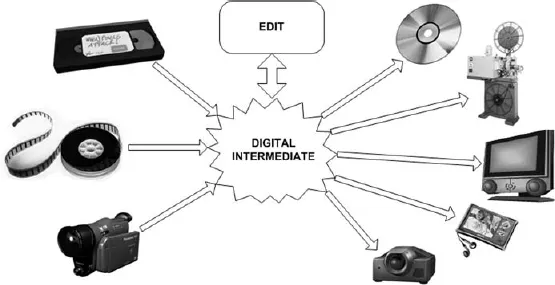

Figure 1–1 With a digital intermediate pipeline, it’s possible to work with a number of different media

The nature of video also meant that creating effects, such as splitscreens or dissolves, was possible but required dedicated hardware for each function. Suddenly a fully equipped video-editing suite was crammed with various boxes, each of which required specific training to use, not to mention cost to install and maintain.

With the advent of nonlinear editing systems, computer technology brought a digital intermediate of sorts to the video world. Rather than record video from one tape to another, it was captured onto a computer system, which then was used for editing in a nonlinear fashion, allowing video editors to work with far greater flexibility. Once the virtual editing (or “offline” editing) had been completed, there were two possible routes for output. In some cases, the details of the edit could be sent to a linear system, and the original tapes were used to recreate the desired cuts in what was termed the “online” edit. Alternatively, the offline version could be output directly to tape from the digital system, complete with dissolves and other effects. Over time, the possibilities grew, such that it became possible to perform sophisticated color-grading of footage, along with numerous other effects. Now, much of the same technology is available to the amateur videographer as to the professional.

1.3 Digital Intermediates for Film

Back in the “golden era” of film production, perhaps thousands of feet of 35mm negative (the same stuff you put in a nondigital stills camera) would be generated every day of a shoot. All this film would have to be soaked in numerous chemical baths, and then it would all get printed onto more film—this time 35mm “positive” (or “reversal”) film. This process allowed a light to be shone through, projecting the image onto something (e.g., a cinema screen) in the correct color for viewing.

So, at the end of shooting a production, you would have maybe a million feet of celluloid, at which point would come the editors to sort through it all, which had to be done by hand. But because the negative is so fragile and yet so valuable (each bit of original negative retains the highest level of quality and represents all the set design, acting, camerawork, and lighting invested in it), there was constant risk of damage to it, particularly during editing but also during duplication and printing.

More copies of the negative were created for the editors to work with, and once they had decided how it was going to cut together, they would dig out the original and match all the cuts and joins they made (and they really used scissors and glue to do it) to the original.

So now there would be a cut-together film, which consists of hundreds of valuable strips of film, held together by little more than tape. Woe unto any filmmaker who decided they wanted to make changes to it at this point.

Other problems still had to be dealt with. First of all, you don’t want to keep running a priceless reel of film through a duplicator every time you want to make a cinema print (especially bearing in mind that you might need to make some 10,000 or more prints for a distribution run). Second, different scenes might have been shot on different days, so the color would need adjusting (or would require being “timed”) so that the different colors matched better.

Hence the internegative and interpositive copies of the original, cuttogether film. Creating these additional reels allows for color timing to be done too, and so the result is a single piece of film with no joins. So now everyone is happy, even after running it through the copying machine 10,000 times.

Well, almost. See, the internegative is of significantly lower quality than the original, and all the color timing is done using a combination of beams of light, colored filters, and chemicals, which is a bit like trying to copy a Rembrandt using finger paints. But until the digital intermediate process gained a degree of authority, filmmakers (and the audience) just lived with the limitations of the photochemical process.

Things improved a little with the advent of nonlinear video editing. It basically meant that rather than having to physically wade through reels of film to look at shots, copies of all the film could be “telecined” (i.e., transferred) to videotapes and edited as with any other video production, finally matching the edit back to the individual strips of film. But many of the quality issues remained, and filmmakers were still unable to match the degree of stylization achieved in video production without resorting to visual effects (and at significant cost).

At least, not until the advent of the digital intermediate process for film came into use, offering significant advantages over the traditional, optical...