![]()

Part I

Classroom, school and LEA: the Leeds report

![]()

Chapter 1

The Primary Needs Programme: overview

ORIGINS

After the 1974 local government reorganisation Leeds became the third largest city, by population, in England. To many, this is a surprising statistic, since even now, in the 1990s, when it is enjoying an economic boom which has placed it ahead of most of its northern rivals, Leeds has far less of the appearance or feel of a big city than, say, Liverpool or Manchester: but while after 1974 these two cities lost population to the satellite towns of Merseyside and Greater Manchester, Leeds gained a substantial part of the old West Riding county.

For the new LEA, the result was a mixture both of educational traditions and of patterns of school organisation. The West Riding, under its former Chief Education Officer Alec Clegg, had been one of England’s showcases for progressive primary education and for experiments in organisation (middle schools) and social intervention (educational priority areas). Leeds, though not untouched by these ideas, had remained, in contrast, educationally–and for some of the time politically–conservative. At the start of Leeds City Council’s Primary Needs Programme (PNP), the initiative which forms the subject of this study, the 230 Leeds primary schools ranged in size from former West Riding village schools with a handful of children to large innercity schools with up to 600 on roll. Their pupil age–spans included 5–7, 5–8, 5–9, 5–11, 5–12 and 7–11. By 1988, the average primary school size in Leeds was 191 (close to the then national average), with a school population of 48,000 pupils and 2,400 teachers.

For many years before the inception of the Primary Needs Programme, Leeds was consistently low in LEA league tables of primary school per capita educational spending and pupil-teacher ratios. The Authority operated a ‘ring-fence’ policy on new primary teacher appointments, and advisory and support services were, by comparison with many other LEAs, very thinly spread. These factors, combined with a relatively low rate of teacher mobility, generated a primary schooling system which by 1985 was perceived by the local politicians who inherited it to be stagnant and old-fashioned, though it also had, as do all LEAs, its pockets of excellence.

The Primary Needs Programme originated against this background, and should be seen first and foremost as a serious attempt to shift resources on a large scale towards the city’s primary sector in order to reverse years of decline. Primary education, at last, was deemed to be an area of high priority. (For a more detailed discussion of the background to PNP, see Alexander et al.1989: 1–7.)

In 1984, the Department of Education and Science invited bids from LEAs, under its Education Support Grant (ESG) scheme, for funding to improve the quality of education provided in primary schools in urban areas. Leeds LEA made a successful application for a five-year project which started in April 1985 (Leeds City Council 1984a). Though the ESG project was rapidly overtaken and indeed submerged by PNP, it served as the latter’s prototype and provided a legitimation, if one was needed, for the Authority’s 1985 decision to increase its own resources for inner-city primary education. The goals and strategy for the ESG programme, as proposed to DES, were very similar to those which emerged a few months later as the Primary Needs Programme (Lawler 1988).

The inception of PNP was complicated by the fact that there were four competing views of the nature of the ‘primary needs’ which were to be addressed. These are mentioned here because their persistence generated ambiguities in policy and confusion in teachers’ understandings of PNP which caused serious difficulties at first, especially in Phase I schools, and indeed continued to generate tensions for the entire five-year period of our evaluation. The competing priorities were:

• provision for children with special educational needs in mainstream primary schools;

• provision for children in inner-city primary schools suffering social and/or material disadvantage;

• the improvement of standards of literacy and numeracy (especially reading) among inner-city children;

• the improvement of the quality of primary education across the city as a whole.

These priorities were not in themselves incompatible, but because they had different points of origin in the LEA and reflected competing territorial and political ambitions, teachers found themselves being offered varying and sometimes conflicting versions of PNP’s nature and purposes.

AIMS

The aims of PNP, as they were published by the City Council in 1985, sought to reconcile these views. There was one overarching aim:

• to meet the educational needs of all children, and in particular those children experiencing learning difficulties;

• and three specific goals by which this aim would be realised:

• developing a curriculum which is broadly based, with a stimulating and challenging learning environment;

• developing flexible teaching strategies to meet the identified needs of individual pupils, including specific practical help for individuals and small groups, within the context of general classroom provision;

• developing productive links with parents and the community.

(Leeds City Council 1985a)

Three problems were provoked by these frequently quoted statements. First, the problem of ambiguity: from the outset, and for much of the programme’s duration, many school staff were uncertain whether PNP was about the special educational needs of certain children or the provision of ‘good primary practice’ for all. Second, the problem of amorphousness: even assuming the first matter was clarified, few of the phrases in the three enabling or subsidiary goals conveyed any clearly defined meaning. Finally, the problem of application: it was difficult to see what practical function, if any, aims expressed in this way could usefully fulfil.

Despite such difficulties, these remained the Primary Needs Programme’s officially endorsed goals. They featured in numerous documents, job specifications, courses and other LEA statements and provided the framework within which heads and teachers were expected to work. Necessarily, of course, they were also the starting point and continuing point of reference for the evaluation which the Council commissioned from Leeds University in 1986.

Whatever its subsequent achievements, the lack of carefully worked-out, clearly expressed or seriously regarded aims represents a basic weakness of the Primary Needs Programme as educational policy. The programme lacked the precision of focus and direction which would have enabled the substantial resourcing to be exactly targeted. Our data show that as a consequence these resources, especially the PNP coordinators, were in some schools channelled into activities which bore little relation to the programme’s goals as officially interpreted, yet which could nevertheless be justified in terms of the goals as stated because of their ambiguity.

The problem of amorphous language in the Authority’s policy statements on primary education was not limited to the PNP aims, as we show both in our interim reports and in this book. Indeed, if this had been a feature of the aims alone its consequences would have been considerably less serious, since aims by their nature tend to be somewhat broad and sweeping, and need to be given operational meaning through objectives and strategies. Nor is this a problem peculiar to Leeds. It is in fact a characteristic of much of the post-war professional discourse in English primary education, and the case for many of the ideas and practices prominent during this period was often weakened by the way they were expressed and discussed. Equally, professional dialogue of the kind required for the improvement of practice was sometimes frustrated by the absence of shared or precise meanings (Alexander 1984, 1988). There is no reason, however, why an LEA cannot give a lead in its own documents and courses in promoting greater clarity and precision about the purposes and processes of primary education.

The tension between the ‘special needs’ and ‘good primary practice’ views of PNP persisted partly because of an institutional separation and indeed rivalry between the departments responsible within the Authority for primary education and children with special educational needs. Moreover, major components of PNP, like the 7+ and 9+ reading tests used to determine PNP phasing and levels of resourcing, were administered from outside the Primary Education Division. Such separation is common in English LEAs and has been criticised by HMI as likely to frustrate the integrative goals of the 1981 Education Act (DES 1989a). The LEA took note of our earlier comments on this matter (in the seventh interim report–Alexander et al. 1989, ch. 2) and from May 1990 the integration of the Authority’s advisory services had begun to produce much more effective inter-divisional consultation.

Many of these problems stemmed from the speed with which PNP was conceived and introduced. To achieve such a radical shift in policy and resources in so short a time was impressive, but against this should be set the confusion referred to above and the professional disaffection discussed in later chapters. The Authority itself recognised and acknowledged the latter, and in subsequent policy matters was more scrupulous in consulting interested parties.

PHASES AND CRITERIA

PNP was introduced in three phases. The seventy-one Phase I schools were identified by reference to two criteria: educational need and social need. The measure of educational need was an analysis of each school’s scores on the Authority’s 7+ and 9+ reading screening tests. The extent of social need was determined by the proportion of children in each school qualifying for free school meals. The process was designed to ensure that those schools with the greatest need received the earliest and most substantial resourcing, starting in September 1985. The fifty-six Phase II schools were introduced on a similar basis in January 1987, and the remaining 103 schools entered the programme, with a rather smaller budget spread more thinly, in September 1988.

Crude though the phasing measures may seem, our analysis shows them to have been, by and large, reasonably accurate indicators of schools’ needs in respect of the two criteria in question. However, there were a number of anomalies, among which the most notable and contentious were the several small Phase I schools in affluent areas where low pupil numbers produced distortion in the reading score analysis. This generated a certain amount of resentment among staff in other schools, partly because they felt they had manifestly greater problems than some of the schools selected for Phase I, and partly because they felt that some of the anomalies were tantamount to a reward for professional inadequacy, or that, conversely, they themselves were being penalised for professional competence.

In a sector as resource–starved as primary education, especially given the particular situation in Leeds referred to above, such reactions are inevitable. The important issue here would seem to be that at least the Council was prepared to commit substantial additional funds to primary education and to seek to devise a fair scheme for ensuring that these were targeted in accordance with policy. However, it is worth noting that such crude measures for selective targeting are bound to produce anomalies, and the government’s scheme for the local management of schools (LMS) may well, on a much larger and more complex scale, introduce similar difficulties and reactions, since the approved LMS formula for Leeds includes weightings for needs derived directly from those used in the Primary Needs Programme (Leeds City Council 1989c).

RESOURCES

Between 1985 and 1989, the Council invested nearly £14 million in its Primary Needs Programme. The main areas for expenditure were:

• additional staff;

• increased capitation;

• refurbished buildings;

• in-service support.

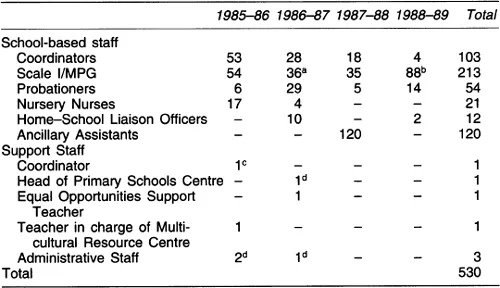

The 530 additional staff appointed between 1985 and 1989 under PNP, at a cost of £11,428,000, comprised the following:

• 103 PNP Coordinators (Scale II/III, MPG with/without allowance after 1988);

• 213 PNP Support Teachers (Scale I, MPG after 1988);

• 54 Probationers;

• 21 Nursery Nurses;

• 12 Home–School Liaison Assistants (later called Liaison Officers);

• 120 Ancillary Assistants;

• 1 Coordinator of the Primary Needs Programme;

• 1 Head of the Primary Schools Centre;

• 1 Primary Support Teacher (Equal Opportunities);

• 1 Teacher in Charge of the Multicultural Resource Centre;

• 3 Administrative Staff.

The year-by-year breakdown is shown in Table 1.1.

The senior and most innovative of the PNP school–based appointments were the PNP coordinators, most of whom had a general, cross–school developmental brief, but a small number of whom were appointed with a multicultural brief only. The assimilation of pre–1988 coordinator appointees to the 1988 salary scales gave rise to difficulties in some schools in terms of each school’s quota of above–MPG allowances. Similarly, the later appointees could find themselves undertaking a job defined as senior and responsible but being paid the same as ostensibly junior colleagues. This problem was not of the Authority’s making, and it did its best to resolve it equitably. The role of PNP coordinator is discussed in Chapter 6, and in greater detail in our fifth interim report (Alexander et al.1989: ch. 5).

Table 1.1 Appointments to the Primary Needs Programme, 1985–89

Notes: a Includes five half-time appointments

b Includes twenty-eight half-time appointments

c For one year only

d Until 1987–88, when absorbed into central administration

Each PNP appointee worked to a job specification. At first, the brief for the PNP coordinator was unrealistic in terms of the time available and the wide range of expertise required: it was subsequently modified by the Authority.

The appointments of the 120 ancillary assistants in 1987–88 were anomalous in the sense that they were mainly of staff redeployed from other Council departments as a result of financial cuts rather than part of the original conception of PNP; they were none the less useful for that.

Between 1985 and 1989 the Council allocated a total of £461,000 to enhance schools’ existing capitation. Schools prepared bids specifying and costing their requirements which were then vetted by advisers before being forwarded to the Special Programmes Steering Group for formal approval. A detailed analysis of this spending is contained in our eighth interim report (Alexander et al.1989: ch.4) and is referred to in later chapters.

PNP incorporated a £1.9 million Minor Works Programme of refurbishment to some of the least satisfactory buildings–other than those whose state was such as to warrant replacement–in each phase. Each school was tackled differently, but the refurbishment could include some or all of the following:

• new furniture;

• provision of display boards and curtains;

• repainting;

• carpeting;

• lowering ceilings;

• removing walls and changing layout.

The number of refurbished schools in each PNP Phase, to 1989, was as follows:

• Phase I: 16

• Phase II: 6

• Phase III: 3

The fourth major area of investment under PNP was in the in-service education of teachers (INSET). Because of the separate funding arrangements for LEA in-...