![]()

1

Playbill: Introduction

Using the metaphor of the theater that frames this book, consider your role among the troupe of educators dedicated to energizing and revitalizing secondary teaching and learning.

Collaboration works. One-person productions lack the multiple perspectives and spontaneous improvisations that human interactions inspire. In contrast, most award-winning shows feature synergistic casts that captivate sell-out audiences to share visions that linger long past performances. So too, in the theater of teaching.

Collaboration empowers and liberates teachers as learners and professionals. My experiences as secondary teacher and district supervisor, university researcher and staff developer, college professor and student teacher supervisor have demonstrated enduring values of collaboration. Working with others, I have shared ideas, taken risks, and studied results. Initiative and ingenuity have helped us reorder priorities and reorganize physical space, social interactions, and curricular emphases for more effective teaching and learning.

We have extended similar options to students as well. Student voices are rarely heard and their interests often remain outside the classroom. Deficit models label students negatively, rather than question the system or standards of the status quo. In direct contrast, we have afforded students active roles in decision making, which enabled them to identify and develop strengths, while finding personal relevance in educational pursuits.

A progressive philosophy permeates my career. I stress the necessity for learners to construct meaning, I promote the power of literacy across the curriculum, and I highlight the significance of increasingly diverse student populations. By embracing teachers and students as lifelong learners, I have created collaborations that have sparked the rewards of joint curriculum design.

Background

The impetus for this book began over 25 years ago when I first entered the field as a secondary English teacher, caught in the middle of change. I observed that well-respected, veteran teachers controlled all aspects of the learning situation, whereas younger colleagues tried individualized instruction. Mentors directed me toward control mechanisms, but possibilities inherent in spontaneity intrigued me.

I recalled how I had preferred leeway in my own studies from elementary through graduate school. Being asked to direct learning for all my students felt artificial and contrary to my own experiences as a learner. Tensions between what I was doing and what I believed led me to improvise. I conferred with students and began to experiment with single sessions, then units of study. Gradually, I restructured my whole approach to teaching to reflect my underlying belief in the learner.

Outside the classroom, other events furthered my understanding of teaching and learning. The first time I was involved in writing curriculum, I worked with colleagues from other buildings in a large district. Like a summer stock company, we had 6 weeks to get acquainted, pool our strengths, and produce a writing guide for ninth-grade English teachers. We explored ideas and strategies in a lively exchange.

That experience proved rewarding for me and helpful to many teachers who found the suggested structure and sequence useful. But, administrative approaches varied across buildings and other teachers felt compelled to follow the ideas and lesson plans in strict order, page by page. This realization bothered me because I had always resisted “teacher-proof” materials that undermined self-expression and creativity. When the district employed a few faculty members to write a guide for others, they may have been well-intentioned, but too many interested parties felt silenced.

Years later, as a district supervisor of English in another large district, I introduced whole language concepts to the secondary level, in hopes of developing the voices of students and teachers. Some colleagues welcomed change and willingly embraced the premises of learning language through integrated, personalized use. But, some changes proved subtle, others only temporary. Colleagues who resisted did so not just on philosophical grounds. Instead, dedicated teachers raised concerns about content coverage, administrative demands, and parental expectations. The system stymied risk taking.

Juggling these curricular issues forced me to rethink the definitions of education, teaching, learning, and knowledge. In order to examine conflicting perspectives, I pursued a doctorate in curriculum and teaching. My studies furthered my belief in the individual learner and progressive education, which opposed the standardization of learning connected with traditional teaching.

At the university level, my collaborative research centered on the curricular issues and concerns voiced by progressives and the English departments with whom I had worked. Some clear insights emerged: (a) Greater depth rather than breadth of coverage led students to clearer understanding; (b) more opportunities for choice increased student motivation for learning; and (c) learner ownership and active participation engendered more effective learning.

Joint control of curricular decision making improved learner confidence from teachers to students, in a domino effect. We drew from each other’s experiences and shared knowledge and insights to solve problems and draw conclusions. As a result, we all found pride in ourselves and our work (Gross, 1992a).

I continue to learn in the undergraduate education classes I currently teach. Students often question the freedom of choice regarding course emphasis, research topics, and due dates; they doubt the efficacy of the progressive philosophy I state up front. Some students ask me to tell them what I want; others assume they should repeat what I believe. Gradually, they realize I expect them to research issues of interest and express informed opinions (Gross, 1996).

Throughout my career, I have enjoyed working with teachers and students, to study issues and brainstorm solutions, to liberate thinking and multiply alternatives for more effective learning. Personal experiences have compelled me to share insights that have emerged from collaborations in hopes of inspiring others.

What professional collaborative efforts have you pursued? What role(s) do you expect to play over the next five years? How will you accomplish your goals?

Rationale

Teaching is a dynamic, ever-changing endeavor. Each success proves to be but a hint of things to come—new challenges, new discoveries. The excitement of learning led us to the teaching profession. Why not spread our enthusiasm for learning by creating an open dialogue with students to encourage interrogation of course content and methods, sustaining conversations on a daily basis?

These ideals may seem elusive for practicing and prospective teachers who often lack support or freedom to experiment. Logistics such as scheduling constraints or concerns about content coverage and standardized tests can obstruct endeavors to invigorate teaching and learning. Teachers often struggle to meet conflicting and external demands, with little support from in-service sessions that often lack clear direction or follow-up. In addition, many education courses fail to model the principles they espouse. Student teachers wrestle with theories of the latest research regarding teaching and learning, but remain unfamiliar with, and uninformed about, how to transfer these concepts into lesson planning and activities (Britzman, 1991).

Whether you are a teacher or a student teacher, you deserve better and so do your students. Countless resources lay wasted or overlooked, leaving too many individuals to operate in isolation. Joining forces stimulates higher thinking levels and creativity. Partners in learning augment possibilities for students and teachers. Powerful rewards of learning through collaboration are too valuable to be left to chance.

Need for Collaborative Curriculum Review

Curriculum constitutes the core of formal education, yet its composition and components are not always clearly stated, readily known, or regularly reviewed—especially by those most influenced and affected by it. Curriculum guidelines need to become more explicit and open to question. Curriculum changes must entail greater clarity and strive toward stronger coherence. Rather than leave curriculum decisions for district committees or textbook publishers, teachers and students deserve to confer about (a) the purposes and content of a course, (b) the methods of implementation, and (c) the means of assessment. As the individuals most closely associated with learning, teachers and students are suited to shape curriculum.

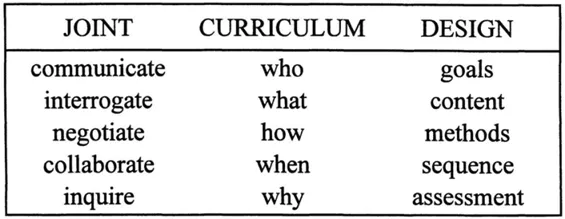

Dynamic and probing, joint curriculum design posits open examination of approaches to learning by teachers and students in relation to course content. Figure 1.1 lists key concepts behind building curriculum through ongoing dialogue. Curriculum issues and components unfold whether you read the chart vertically or horizontally.

Fig 1.1. Key concepts represented in joint curriculum design, which stresses student and teacher interaction to analyze curriculum issues and components.

Vertically, five verbs describe essential kinds of interaction that involve students and teachers in joint analysis of curriculum; five questions probe vital, interrelated issues of curriculum; five components imply the coherence and comprehensiveness of the collaborative design endeavor.

Reading the chart horizontally specifies connections: (a) Students and teachers who communicate goals, envision and strive toward common aims; (b) they mutually interrogate what content choices stimulate inquiry through individual and group interests; (c) they negotiate methods of how to proceed to accommodate individual needs and learning styles; (d) they collaborate to sequence when sufficient exploration and practice lead to comprehension; and (e) they devise assessment criteria to specify why to inquire into topics and determine expected outcomes.

Therefore, joint curriculum design is a process that may be defined as follows: Joint curriculum design is an interactive form of planning that unites teachers and students in a joint appraisal of curricular components to negotiate goals, content, methods, and assessment throughout the various stages of planning, implementing, and debriefing.

Joint curriculum design is based on mutual trust and partnership, openness and flexibility. For example, I began applying joint curriculum design toward research writing in an average tenth-grade English class. I negotiated terms and time frames with students. We established goals and objectives, criteria for topic choices, research sources, written drafts, and final presentations. I taught research skills and served as a resource, but students also consulted with one another. Originality surfaced through self-selected collaborations and quality of work escalated. Joint curriculum design freed students to explore, confer, invent, and perform.

Considerations for Joint Endeavors

How do you and your students use your time together? What ideas and explorations excite everyone? What plans do you enact and why? What other possibilities exist?

If you invite students to critique curriculum, to join in examining what occurs in the classroom and why, students prove anxious to learn, willing to work, and eager to share new insights. Working together to uncover bases of curricular decision making, you engage in (a) recognizing common goals, (b) adjusting inconsistencies, and (c) sharpening the focus and direction of learning.

Joint curriculum design empowers students and new or experienced teachers. Stories recounted in this book affirm the innate curiosity, natural drive, and unique perspectives of students and teachers as learners. In the joint learning process, teachers and students achieved new respect for each other and for their accomplishments.

Thus, joint curriculum design moves away from traditional teaching and centers around teamwork. Instead of relying solely on the teacher, students act as valuable players with constructive suggestions to inform the process of teaching and learning.

Joint curriculum design does not dismiss the past, but recognizes the importance of balancing what proved to be effective with how to improve what didn’t. Joint curriculum design invites experimentation, as individuals construct knowledge in personalized ways.

Supporting Theories

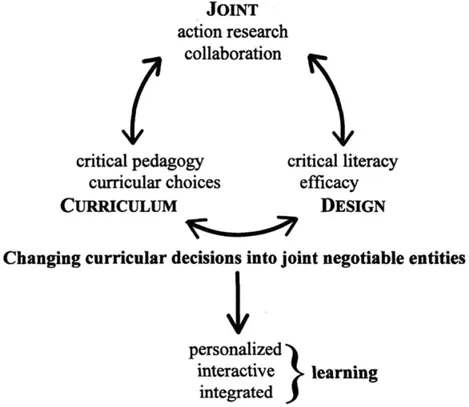

Three working theories help to develop a climate for thoughtful investigation and collaborative innovation—action research, critical pedagogy, and critical literacy (see Fig. 1.2).

Fig. 1.2 Joint curriculum design grounds theories in the process of changing curricular decisions into joint negotiable entities.

Action research into lesson planning, content, and procedures enables teachers to study how decisions and consequences affect learning. Students become co-researchers which allows them to gain perspective, share responsibility, and contribute general insights.

Critical pedagogy frames thoughtful inquiry to effect relevant change. Joint analysis by teachers and students of course content and process isolates salient issues and identifies effective forms of investigation. Democratic classrooms train students to become critical thinkers and change agents later on in life.

Critical literacy strengthens thought and expression. Critical reading and listening facilitate ways to refine performance skills. Well-chosen written and spoken words increase clarity and cogency. Effective communication reaches a greater audience.

Thus, this book explores the potential of changing curricular decisions into joint negotiable entities. Joint monitoring of classroom actions and agendas enables teachers and students to appreciate the benefits of collaboration, the impact of curricular choices, and the efficacy of language for the present and future.

Examples of Collaborative Changes

This book centers on years of research with veteran and aspiring secondary-level teachers and their students. Speaking from diverse perspectives, students and teachers express initial misgivings, frequent surprises, and welcome rewards of developing curriculum collaboratively. Accounts explore transitions and represent positives and trade-offs of learning through jo...