- 344 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Architectural Design Procedures

About this book

This book explains how architects obtain and administer work from the moment the contract is signed, to the handing over of the finished building to the client and is an indispensible guide to all architecture students.

This second edition has been thoroughly updated and expanded. It now includes significant additions to the section on design constraints, a new section on quality assurance and management and information on new acts and regulations introduced since the publication of the first edition. Other sections on subjects such as the Building Regulations, use of computers and standard forms and letters have been brought up to date.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture General1

Setting the scene

1.1 The beginning

Every building begins in the mind of one person. It may be someone wanting a home built for their family, or a speculator wishing to build a block of flats to sell for a profit. It may be a trader seeking a shop to dispose of their goods, or an industrialist needing a factory in which to manufacture products. It may be a Christian with ambition to create a building to advance their religious belief, or an enthusiastic golfer anxious to construct a golf clubhouse. The building may be required for pleasure, income, utilitarian uses, or many other purposes, but almost invariably the initial impetus comes from one person recognising a need and deciding to do something about it.

In most cases other people – family, friends, colleagues, associates – will soon become involved, and may even take over the idea of providing a particular building as being their own, and either jointly or by themselves assume responsibility for commissioning the work.

At some stage too, the innovator, unless he possesses the necessary expertise in design and building – or thinks he does – will seek professional advice to help translate ideas into a completed building.

1.2 Enter the architect

Traditionally, the first person the innovator will generally turn to, although he may not always be quite sure what to expect, is the architect. Nowadays the practice of architecture is extremely complicated. Some see it as a combination of understanding different architectural styles, possessing artistic sense, and being able to create buildings which delight the eye. Others view it as possessing skills in construction technology and applying them to the design of buildings. In truth it is both these things, but to be really successful and efficient architects, as well as having artistic and technological skills, also need at least a working knowledge of laws, regulations, customs, costs, business, and much more, such as spaces, circulation patterns, access, and special needs.

Essentially, the architect is employed by the client to act as his agent and see that he is provided with a building which will satisfy his needs. To achieve this, the architect, with the approval of the client, has to make a series of choices. First, he will be concerned that the building will satisfy the functional requirements of the occupants. Second, he has to decide how to make the building attractive to look at. He will be concerned with massing, proportion, unity of the various parts, and choice of the right materials. Third, he will have to choose a suitable structural form, and appropriate finishes and services, taking care that the completed building will not incorporate any defects. There will also be choices to be made which relate to costs. Often the architect’s decisions will affect running costs and maintenance costs for the future life of the building. The architect will be concerned with many other practical matters, such as how to minimise the danger and inconvenience of fire damage, noise transmission, and thermal loss.

In all that the architect does a decision will have to be made as to how the requirements of a complicated network of regulations, standards, and legal requirements are best met. Finally the architect must choose the right way to manage the actual building operations.

1.3 The arrival of the architectural technologist

In the past many architect’s practices employed staff known as architectural assistants. Sometimes they worked alongside qualified architects and performed identical roles. In many of the smaller firms the principals were the only qualified architects, and virtually all the drawing work, and much of the design work, was undertaken by ‘unqualified assistants’. They may have been employed because they were cheaper than their qualified contemporaries, but some firms preferred to use them because of their wide practical experience.

Occasionally, architectural assistants would set themselves up in business, generally operating as a one-man band and using descriptive titles, such as ‘architectural consultant’ or ‘architectural designer’, which would avoid conflict with the Architect’s Registration Council (see section 2.6 of chapter 2).

At a conference on architectural education held in 1958, the needs of the architectural assistants, who by now were becoming known as architectural technicians, were recognised. The 1958 conference resulted in a report, in 1962, entitled The Architect and his Office’, which arrived at the conclusion that ‘there should be an institute for technicians, sponsored by the RIBA to ensure the maintenance of standards of education and training’.

In 1964 the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) provided a grant to establish a national organisation which was called the Society of Architectural and Associated Technicians’ (SAAT). In 1969 the SAAT became an associated society of the RIBA.

On reflection, many years after the event, there is a case for saying that ‘technician’ was not the best possible choice of word. Dictionaries define a technician as ‘one skilled in a practical art’, whereas the technologist is equated with ‘the practice of applied science or art’. However, in 1965 when SAAT was founded, ‘technician’ was a popular job title. It was used by the Business and Technician Education Council (BTEC) for people in various disciplines whose role appeared to be to assist degree-level and chartered qualified members of various professions. The role of the architectural technicians, as perceived by BTEC, was stated as being ‘to interpret, collate and present design information for use by the construction sector; collaborate with, and take instruction from the architect on the design requirements for a project’.

The RIBA had rightly identified the need for an organisation to represent the aspirations of architectural personnel who did not possess any formal qualifications. SAAT was soon firmly established and developed into an influential national organisation. There was, however, some uneasiness about the name, which eventually led to SAAT with the support of its membership, the RIBA and the Architect’s Registration Council of the United Kingdom (ARCUK) becoming the British Institute of Architectural Technicians (BIAT).

The function of architectural technicians developed, and to some observers their role appeared to be similar to that of people in certain other countries who were designated ‘technical architects’.

A member of the BIAT staff, David Wood, writing in the BIAT 1988 Yearbook, provided further clarification of the role of the architectural technician at that time:

The architectural technician is principally an architectural technical communicator, forging the link between theory and practice. The technician’s role is therefore complementary to that of the architect, his main overriding concern being the sound technical performance of the building.

In 1994 BIAT again changed its name, this time to the British Institute of Architectural Technology (BIAT). This was attributed in BIAT’s 1996 report Into the 21st Century’, because of ‘the development of degrees and S/NVQs in architectural technology, first mooted in the early 1980s, and the need to gain recognition in Europe’.

In their overview of the situation, which was included in the 1996 report, BIAT stated ‘the Institute and the discipline of architectural technology are now firmly established as a vital component of the construction industry’.

The role of the architectural technologist is further discussed in section 2.7 of chapter 2.

1.4 The building team

As well as possessing the multitude of talents outlined above, the architect should also possess the ability to work as a member of a team. As has already been stated, in a traditional format the architect is likely to be the designer, and lead the design team, but he is only one member and will rely on the help and cooperation of all the team members to translate his ideas into a finished building.

There are others within the building team, besides the architect, who can act as designer and team leader, and this will sometimes happen.

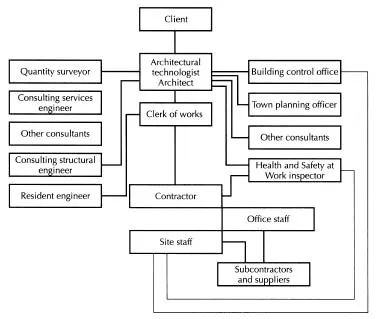

The four main groups involved in the design and construction of a building are the client, the design team, the contracting team, and the statutory authorities. The roles of team members are summarised below and the relationship between members is illustrated in Figure 1.1.

Fig. 1.1 The building team

The client

The client is also known as the building owner, and in the building contract is generally referred to as the employer. The client may be a single individual, a small private company, a large public limited company, a local authority, a state corporation, a voluntary society, or practically any other organisation you can think of.

Essentially, the role of the client is to tell the architect or architectural technologist his requirements, commission the works, and either directly or indirectly ‘employ’ and pay everyone on the project.

The design team

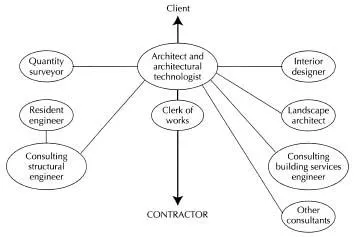

The structure of the design team is illustrated in Figure 1.2.

Architect

As has been mentioned, the role of the architect is to act as the client’s agent in the design and supervision of the building, advising and guiding him as necessary, from inception of the original idea to final completion and occupation of the finished building. His work will include the preparation of the design and drawings and obtaining statutory approvals.

As has been mentioned, the role of the architect is to act as the client’s agent in the design and supervision of the building, advising and guiding him as necessary, from inception of the original idea to final completion and occupation of the finished building. His work will include the preparation of the design and drawings and obtaining statutory approvals.

Fig. 1.2 The design team

Architectural technologist

The architectural technologist will work in partnership with the architect, particularly in the field of architectural technology, but he is often involved in all aspects of the work, including contract procedures and administration. Sometimes he will be responsible for the design, and like the architect take on the role of team leader. This matter is dealt with in more detail in chapters 2 and 3.

The architectural technologist will work in partnership with the architect, particularly in the field of architectural technology, but he is often involved in all aspects of the work, including contract procedures and administration. Sometimes he will be responsible for the design, and like the architect take on the role of team leader. This matter is dealt with in more detail in chapters 2 and 3.

Other architectural staff

In addition to architects and architectural technologists, practices may use other staff with various designations, such as technician, architectural assistant, and draughtsperson.

In addition to architects and architectural technologists, practices may use other staff with various designations, such as technician, architectural assistant, and draughtsperson.

Clerk of works

The clerk of works is generally employed directly by the client but acts as the architect’s or architectural technologist’s representative on-site. The responsibilities of the clerk of works are limited to that of an inspector, without the power to issue instructions on his own authority.

The clerk of works is generally employed directly by the client but acts as the architect’s or architectural technologist’s representative on-site. The responsibilities of the clerk of works are limited to that of an inspector, without the power to issue instructions on his own authority.

Quantity surveyor

The quantity surveyor is employed by the client as his own and the architect’s or architectural technologist’s advisor on anything relating to the cost of the job, including preparing the bill of quantities, checking tenders, and carrying out valuations of costs during the progress of the project.

The quantity surveyor is employed by the client as his own and the architect’s or architectural technologist’s advisor on anything relating to the cost of the job, including preparing the bill of quantities, checking tenders, and carrying out valuations of costs during the progress of the project.

Consulting structural engineer

The consulting structural engineer is also employed by the client, as ...

The consulting structural engineer is also employed by the client, as ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures and tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Setting the scene

- 2 Background to Architectural Practices

- 3 Organisation and business side of architectural practices

- 4 Architectural practitioners and the law

- 5 Technical information

- 6 General office practice

- 7 Design constraints

- 8 General design procedures

- 9 Pre-contract procedures

- 10 Contract procedures

- 11 Standard documentation

- Appendix 1: Glossary

- Appendix 2: Abbreviations

- Questions

- Sources of information

- Recommended reading

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Architectural Design Procedures by Arthur Thompson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.