Chapter 1

Urbanisation and globalisation

Introduction

Over the last 50 years, the world has witnessed a dramatic growth of its urban population, from about 29 per cent of the world’s population in 1950 to 48 per cent by 2003. A recent United Nations projection indicated that from 2000 to 2030 the world’s urban population will grow at an average annual rate of 1.8 per cent, nearly double the rate expected for the total population of the world, and that the 50 per cent mark would be crossed in 2007. Indeed, the world’s urban population is expected to rise to 61 per cent by 2030. Population growth will be particularly rapid in the urban areas of so-called ‘developing world’, averaging 2.3 per cent per year during 2000–30. The speed and scale of this growth pose major challenges, and monitoring these developments and creating sustainable urban environments remain crucial issues on the international development agenda (United Nations 2004).

This chapter aims to review the definitions, trends, components, and implications of the urbanisation process, noting the differences between the early stages of urbanisation, which started in what has been termed the ‘developed world’, and the current processes in the rapidly urbanising world. It will also discuss the linkages between urbanisation and globalisation and the increasing de-linking of urbanisation from economic development, as well as general approaches in managing the urbanisation process.

The meaning of urbanisation

Urbanisation normally refers to the demographic process of shifting the balance of (usually) national population from ‘rural’ to ‘urban’ areas; urbanisation rate (or level) indicates the proportion (e.g. percentage) of the population living in urban areas at a given time; and urban growth rate is a measurement of the expansion of the number of inhabitants living in urban settlements (expressed usually as per cent change per annum). These terms seem to be well defined, but the study of urbanisation is complex, particularly in relation to the definition of ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ settlements.

Despite the fact that the world is becoming increasingly urban in nature, the apparent differences between ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ or town and country are actually not straightforward. The definition of urban itself changes over time and space (Cohen 2004), each country tending to adopt its own definition in an often arbitrary way that reflects different economic and cultural situations. Definitions are usually based on criteria that may include any of the following: size of population in a locality, population density, distance between built-up areas, predominant type of economic activity, legal or administrative boundaries and urban characteristics such as specific services and facilities. Table 1.1 shows examples of the diversity in criteria and definitions in various countries. In general, however, the traditional distinction between urban and rural areas within a country has been based on the assumption that urban areas, no matter how they are defined, provide a different way of life and usually a higher standard of living than those found in rural areas. In many industrialised countries, this distinction has become blurred and the principal difference between urban and rural areas in terms of living circumstances tends to be a matter of the degree of concentration of population (UN 2002).

Linked to the problem of defining urban areas is the difficulty in identifying the population of a given city. This is because the size of a city’s population is a function of how and where the city’s administrative boundaries are drawn (Cohen 2004). Urbanisation levels can be affected by so-called ‘under-bound’ and ‘over-bound’ cities. In the under-bound city the administratively defined area is smaller than the physical extent of the settlement, while in the over-bound city the reverse is true. Obviously, any reclassification (e.g. changes in urban definition, city boundaries, etc.) could change a city’s official population (and the national urbanisation rate) without any actual demographic change (Oberai 1987). Lack of reliable and up-to-date demographic data can also make analysing urbanisation difficult. National censuses are usually the principal sources, but they could be several years old. There is also a tendency for censuses to undercount urban populations, because of a large mobile population (Cohen 2004). The urban/rural definition has been made all the more difficult by the fact that the reality, and consequently the concepts, of what is urban is not static but is subject to change. All this means that the urban–rural division is an excessively crude dis-aggregation. Because there is no global standard, one needs to be very careful when making cross-country comparisons regarding the extent to which particular countries are urbanised.

Trends in urbanisation

The most commonly used urbanisation data come from publications produced by the United Nations Statistics Division. The UN collects, compiles and disseminates data from national statistical offices on population density and urbanisation through the Demographic Yearbook, which includes a set of tables on estimates and projections of urban and rural populations based on the national census definition, which as indicated above differs from one country or area to another. Despite the problems of different definitions, these data provide some useful information on the trends and characteristics of urbanisation in the world. This section draws mainly from the UN data sources.

Table 1.1 Definitions of urban settlement in selected countries

Urbanisation is not new and its roots go back to early history (see Chapter 4), but it only started to grow in a significant way following the industrial revolution, particularly in Western Europe and the United States during the nineteenth century. Industrialisation and the development of modern transportation such as the railways contributed to the process. For example, from 1801 to 1911, Britain’s urban areas accounted for 94 per cent of the country’s population increase. One-third of the urban growth was due to net immigration from rural areas (Lawton 1972). The world’s population increased three-fold between 1800 and 1860 but the world’s urban population increased thirty-fold. It has been estimated that before the start of the nineteenth century only some 3 per cent of the world’s population lived in towns of over 5,000. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the figure is probably about 40 per cent (Carter 1995).

During the first half of the twentieth century, urban population continued to grow fast, particularly in Europe and North America. At the beginning of the century, 60 per cent of the American people lived on farms and in villages, but by 1970, 69 per cent resided in metropolitan areas. Clearly, metropolitan concentration was the dominant feature of population redistribution in the so-called developed world during the first half of the twentieth century (Berry 1981). In the so-called developing world, urbanisation started later, being limited in the nineteenth century in both scale and extent to the areas of Western colonial expansion. During the twentieth century this situation changed dramatically. In 1920, about a quarter of world’s urban population lived in ‘developing’ countries; by 1950 this had increased to 42 per cent.

Between 1950 and 2003, the world’s total population increased from 2.52 billion to 6.3 billion, while the world’s urban population increased from 0.73 billion (29 per cent) to 3.04 billion (48.3 per cent) (Table 1.2). In the more developed regions annual growth of urban population was 2 per cent, while in developing regions it reached a startling 3.91 per cent. From 1975 to 2000, urban population growth in developed regions slowed down to less than 1 per cent due to counter-urbanisation in the United States and Western Europe, while less developed regions maintained a high rate of 3.55 per cent per year. Thus, while in 1950 more than half of the world’s urban population lived in developed regions, by 2003 over 70 per cent lived in developing regions, and hence the term ‘rapidly urbanising world’. Looking at it from the point of view of urbanisation levels within these rapidly urbanising regions, while in 1950 less than 18 per cent of the population there lived in urban areas in 1950, by 2003 this figure was over 42 per cent (UN 2004). In terms of absolute numbers, there are now more than twice as many urbanites in developing regions as there are in more developed countries. Fuelled by changes in the countryside, high rates of fertility, falling death rates and rapid city-ward migration, most developing countries have been transformed from rural to urban societies in two or three decades. The larger cities, in particular, have been expanding rapidly, often doubling in size every 15 years (Gilbert and Gugler 1992).

Table 1.2 Total, urban and rural populations by development group, selected periods: 1950–2030

There are marked differences in the size and proportion of the urban population among major areas of the world (Table 1.3). In 2003, Africa and Asia’s urban population was just under 39 per cent; Europe and Oceania were at 73 per cent; and the Americas had the highest levels of urbanisation, with Latin America and the Caribbean at 76.8 per cent and Northern America at 80.2 per cent. However, the combined number of urban dwellers in Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, Northern America and Oceania (1.2 billion) is smaller than the number in Asia (1.5 billion), one of the least urbanised major areas of the world. Of course, these broad figures conceal considerable variations within each area, particularly in developing regions. Most parts of Africa are far less urbanised, containing many countries where more than 70–80 per cent of the population still live in rural areas. Asia appears to be a little more uniform in its urban characteristics in comparison to Latin America and Africa.

A feature of contemporary urban population growth is the way in which the largest cities appear to have been growing at the most rapid rates, a phenomenon which has given rise to the concept of urban primacy – the demographic, economic, social and political dominance of one city over all others within an urban system (Drakakis-Smith 2000). Once a large city is created, then the attraction it offers in terms of supplies of labour and capital, as well as the concentration of infrastructures, will of itself promote growth and initiate a rising spiral of development. This is partly why the largest cities tend to grow fastest. In the largest cities the greatest opportunities are perceived in education and training, in heath care and in general improvement of living standards (Carter 1995). At the beginning of the twentieth century, only 16 cities in the world contained at least a million people, the vast majority of which were in industrially advanced economies. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, there are around 400 cities around the world of such size, about three-quarters of these in low- and middle-income countries (Cohen 2004: 24). In many rapidly urbanising countries, most large-scale modern activities, forms of social infrastructure and centres of decision making are found in a single major city which, in many cases, is the capital city (Gilbert and Gugler, 1992). This high degree of urban primacy, with a large proportion of the national population living in a single city, is mirrored in the way one city dominates all others.

In recent years, some observers have suggested that the nature of the urbanisation process has been changing, with various terms being used to describe the settlements associated with this process, such as mega-cities and extended metropolitan regions (EMR). These agglomerations are not the same as world cities, a term which describes the key command and control points of the global economy, such as New York, London, or Tokyo (UNCHS 1996) – see below. EMRs are a product of the globalisation of the world economy but refer more specifically to a pattern of urbanisation and city structure that is claimed to be fundamentally different from earlier types of urbanisation (McGee and Robinson 1995). EMRs represent a fusion of urban and regional development in which the distinction between urban and rural has become blurred as cities expand along corridors of communication, by-passing or surrounding small towns and villages which subsequently change in function and occupation (Drakakis-Smith 2000: 21).

Table 1.3 The distribution of the world’s urban population by region: 1950–2030

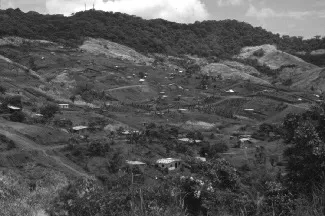

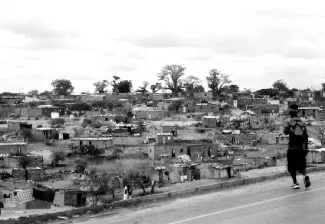

In some geographic regions (e.g. Southeast Asia), urban and rural activities are interpenetrating. Rural economies and lifestyles increasingly assume characteristics that were formerly considered urban. More residents work outside agriculture; rural economies are increasingly diverse, mixing agriculture with cottage industries, industrial estates, and suburban development; and many rural residents are linked to city life through spells of migration and commuting. In some rapidly urbanising regions, mega-urban areas have emerged in which it is difficult to say where a particular city begins and ends. The reconfiguration of urban space is manifested in the outward spread of urban activities, such as industry, shopping centres, suburban homes, and recreational facilities, which are penetrating what was once rural territory (Montgomery et al. 2004: 23) – Figures 1.1 and 1.2. In short, the functions and roles of cities that connect them to surrounding territory are changing in ways that threaten the relevance of administrative boundaries. By blurring boundaries, such changes are causing researchers to question the value of urban/rural dichotomies, which appear increasingly simplistic (McGee 1991; Champion and Hugo 2004).

It is clear from current predictions that the fast growth of the world’s urban population will continue, particularly in developing countries, as is shown for example in World Urbanisation Prospects: the 2003 Revision, produced by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (Population Division) – see Box 1.1.

1.1 Incipient urban development in the rural area of Arraiján, near Ciudad de Panamá (Harry Smith)

1.2 Low-income development in the peri-urban area of Luanda, Angola (Harry Smith)

Box 1.1 Urbanisation prospects

The main findings and predictions of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (Population Division) (2004: 5–8) on the urbanisation process over the next 30 years are the following:

- During 2000–30, the world’s urban population is projected to grow at an average annual rate of 1.8 per cent, nearly double the rate expected for the total population of the world. It was estimated at 3 billion in 2003 (48 per cent of the total population) and is expected to rise to 5 billion (61 per cent) by 2030, while the rural population is anticipated to decline slightly from 3.3 billion in 2003 to 3.2 billion in 2030. By 2007, for the first time, there will be more people living in urban areas than in rural areas.

- The process of urbanisation is more advanced in developed regions, where 75 per cent of the population was living in urban areas in 2003. This is expected to increase to 82 per cent by 2030.

- However, population growth will be particularly rapid in the urban areas of developing regions, averaging 2.3 per cent per year during 2000–30. Almost all growth of the world’s total population in this period is expected to be absorbed by urban areas in developing regions, with the proportion of urban population there expected to rise from 42 per cent in 2003 to 57 per cent by 2030.

- With 39 per cent of their populations living in urban areas in 2003, Africa and Asia are expected to experience rapid rates of urbanisation, so that by 2030, 54 per cent and 55 per cent, respectively, of their inhabitants will live in urban areas. By 2030, Asia and Africa will each have more urban dwellers than any other major area, with Asia alone accounting for over half of the urban population of the world.

- At that time, 85 per cent of the population in Latin America and the Caribbean will be urban.

- In Europe and North America, the percentages of the population living in urban areas are ex...