![]()

Part I

KANT ON THE HUMAN BEING

![]()

As to the subject matter with which we are concerned, we ask that people think of it … as the foundation of human … dignity. Each individual … may reflect on it himself … [Our work] claims nothing … beyond what is mortal.

(Francis Bacon, New Organon, quoted by Kant

in the Critique of Pure Reason (Bii))

“Transcendental Anthropology”

In the introduction, I claimed that Kant's answer to the question “What is the human being?” has at least three different components. Of these, I will refer to the one that made Kant famous and that he identified with “the field of philosophy” (9: 25) as “transcendental anthropology.” The term “transcendental anthropology” is taken from Kant's handwritten notes, in which he refers to an “anthropologia transcendentalis,” a “self-knowledge of the understanding and reason” that would critique all other sciences, including not only “geometry” and “knowledge of nature” but even “literature … theology, law” and “knowledge of morality” (15: 395). But my use of the term arises from Kant's insistence that all of philosophy is reducible to “anthropology” (9: 25) and his description of each aspect of his philosophy as “transcendental” (see A13/B27; 4: 390; 5: 113, 266, 270; 6: 272; and 8: 381). Admittedly, Kant often uses the term “anthropology” for his pragmatic anthropology, and he often reserves the term “transcendental” for investigations of the conditions of possibility of experience (the topic of only one of his Critiques). But he does use both terms in broader ways throughout his works, and “transcendental anthropology” provides a useful term to contrast Kant's approach to the human being in his a priori philosophical works with empirical and pragmatic approaches elsewhere. Throughout his philosophical works, Kant answers central philosophical questions in ways that are “anthropological,” but in a distinctive sense of anthropology that I call “transcendental.”

While this transcendental investigation is contrasted, for Kant, with empirical study of human beings, one must be careful not to confuse “transcendental” with “transcendent” and thereby take transcendental anthropology (or philosophy) to refer to some aspect of human beings that transcends ordinary experience, or our animal nature, or something of that sort. In the same way that God might be seen as ultimately transcendent, we might want to study the transcendent aspect of human beings, through art, perhaps, or by talking about our immortal souls. Kant, however, sharply contrasts his transcendental philosophy with traditional philosophies of the “transcendent.” For Kant, “transcendental anthropology” is a kind of “self-knowledge of the understanding and of reason” (RA 903, 15: 395). By this he does not mean simply that in knowing human beings, we know ourselves, since this would be true for empirical investigations of human beings as well. Instead, in transcendental anthropology, one knows oneself from-within rather than looking at one's psychology from the stance of an observer. Transcendental anthropology is a most immanent self-knowledge, and hence sharply contrasted with both empirical sciences and divine-like transcendence.

The notion of transcendental anthropology as “from-within” is often described in terms of a difference between “first person” and “third person” perspectives, the perspectives of the thinking, feeling, or choosing subject and perspectives on someone as an object. This way of describing the distinction can be helpful if one avoids thinking of “introspective” states as first person, since “from-within” does not imply that transcendental anthropology is “introspective” in any traditional sense. One way of making this distinction clear can be seen in the case of choosing a course of action. Someone observing humans might say that what a person chooses in a particular case is determined by accidental environmental features of which the person is only barely conscious. Or one might introspect and suggest that one's behavior in a particular instance was caused by, say, a combination of anger and exhaustion. The next chapter shows how Kant's empirical anthropology focuses on these sorts of causal explanations of behavior. But when actually choosing, one doesn't consider these accidental and unconscious influences as bases for choice. One looks for various reasons for action, and even if these reasons include what one might in another context see as mere causes of action (say, one's desiring something), they have a different character when one considers them to be reasons to act; they serve not as explanations for behavior but as justifications for it. From within the context of deliberation, one's anger appears not as a necessary cause of action, but as a candidate reason for acting, a reason that one may either endorse or reject. Kant's “transcendental” anthropology characterizes the processes of thinking, judging, choice, and aesthetic appreciation from-within.

The from-within perspective involves an important evaluative or normative dimension. When explaining behavior non-transcendentally, one looks at what the causes of action are, and one need not evaluate whether these causes are “good.” The question whether, say, anger is a “good” cause seems misguided; it either is the cause or it is not. But when thinking about behavior (or judgments, or choices) transcendentally, one looks at reasons for behavior, and reasons invite evaluation. Anger might have caused the behavior, but we can still ask whether it was a good reason for doing what one did. And this is the sort of question one asks, not merely when deciding what to do, but also when deciding what to believe, or how to judge about something, or even whether something is beautiful. The normative question – “Is this a good reason for people to do/think/feel such-and-such?” – arises within transcendental anthropology.

Along with this from-within, normative perspective on human beings, Kant's transcendental anthropology employs a distinctive style of argument. “Transcendental” arguments in Kant proceed from some “given” to the conditions of possibility of that given. Thus Kant's Critique of Pure Reason is an extended argument exploring the conditions of possibility of empirical cognition (what we can know). As an experiencer of the world, one can think about what must be the case for one's experience to be possible, and Kant argues that in order for humans to have the kind of experience that we have, the world must contain substances, laws of causality, and other features, and human cognition of it must be limited in various ways. Similarly, the Critique of Practical Reason argues from the moral law we find valid within deliberation and evaluation to various conditions of possibility of that validity.

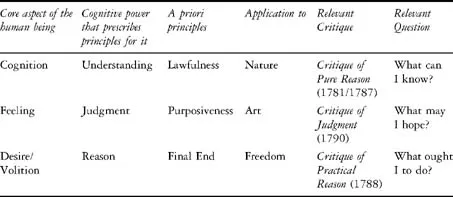

In sum, Kant's transcendental anthropology focuses on what can be known about human beings a priori through an examination of basic mental faculties “from-within” that specifically attends to the conditions of possibility of normative constraints on human beings. The rest of this chapter takes up some details of this transcendental anthropology as it plays out in Kant's three famous Critiques of Pure Reason, Practical Reason, and Judgment. Before turning to those details, it is worth saying a bit more about the specifics of Kant's conception of the human being in order to see how the Critiques hang together as a whole “transcendental anthropology” and thus how “we could reckon all of [philosophy] as anthropology” (9: 25). For Kant, human mental states are divided into cognitions, volitions, and feelings. Each aspect of human beings is governed by its own a priori principles that are prescribed by a distinct higher cognitive power (5: 196). In the Critique of Judgment, looking back on his philosophy as a whole, Kant uses a chart (see Table 1.1) to show how his entire transcendental philosophy can be understood in terms of these different human faculties (5: 198).1

Table 1.1 Kant's transcendental anthropology

What Can I Know? The Critique of Pure Reason as Transcendental Anthropology of Cognition

Kant's most famous and important work, the Critique of Pure Reason, focuses on a particular human capacity: “getting to the bottom of the faculty we call the understanding and … the determination of the rules and boundaries of its use” (A xvi). Kant is not interested here in the empirical question of how the understanding operates, but in giving an account of the rules under which it must operate and the limits that these rules imply for how far we should seek to extend our knowledge. Kant starts with an interest in the status of traditional metaphysics, which involves claims that are “a priori” in that they are necessary and thus not based merely on empirical generalizations, but also “synthetic” because they put together concepts to make substantive assertions about the world. But this metaphysics raises “the general problem” of the Critique of Pure Reason: “How are synthetic judgments possible a priori?” (B19, cf Prol. 4: 276). In answering this question, Kant aims to answer the question “What can I know?” as it applies to the “objective validity” of “a priori concepts” (A xvi), that is, “what and how much can the understanding and reason cognize free of all experience?” (A xvii). Through this transcendental anthropology of cognition, Kant defends a metaphysics that consists in a priori claims about the nature of the world and lays out an epistemology that limits the scope of such claims.

Kant's answer to the question of the possibility of synthetic a priori knowledge depends upon conceiving metaphysics as a subset of transcendental anthropology. From the beginning of his Critique, Kant makes his radically human-centered metaphysics clear:

Up to now it has been assumed that all our cognition must conform to objects; but all attempts to find out something about them a priori … have, on this presupposition, come to nothing. Hence let us once try whether we do not get farther with the problems of metaphysics by assuming that objects must conform to our cognition.

(Bxvi)

To move human cognition into the center of metaphysics, Kant begins by isolating an assumption of prior metaphysics, the assumption that in order to know anything about the world, our judgments about the world have to conform to the way the world really is. Kant claims that this assumption has made progress in metaphysics impossible. Previous philosophers – especially during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries – either sought philosophical systems based upon reason alone (rationalism) or sought the ultimate foundations of knowledge in experience (empiricism). Empiricists fail to account for the aprioricity of metaphysics, while rationalists fail to properly account for its synthetic status (by mistakenly overestimating what reason alone can do). Kant's Copernican turn is based on the thought that empiricists and rationalists fail because both are looking for a way to make human cognitions fit onto an independently given world of objects. There is better hope of showing how a priori synthetic judgments are possible if one assumes instead that the world of objects must conform to the structure of human cognition (B xvi). If the world conforms to our cognition, we can know about the world based on the structure of our cognition rather than by induction from experience.

Kant's next move both limits the scope of this Copernican turn and helps show how it functions to make substantive (or “synthetic”) a priori knowledge possible. Kant claims that humans' thoughts about objects have two components – an active component by which we think about objects, and a passive component by which thoughts are about objects: “Thoughts without content are empty, intuitions without concepts are blind” (A50–51/B74–75). Knowledge of an objective world involves receiving “intuitions” from the world and processing them using one's concepts.

Kant's appeal to “intuitions” – a technical term for that which is given by sensibility – limits the scope of the Copernican turn. Kant does not claim, and need not claim, that everything about the empirical world is determined by the structure of human cognition. Because we have a receptive faculty, humans have knowledge we take from the world, such as that there are mountains in the Pacific Northwest of North America, that water freezes, that dogs and cats cannot interbreed, that large material objects are made of small molecules. And there are other claims that are false, but if true, would have to be discovered empirically, such as the existence of the Loch Ness monster, or fairies, or solid crystalline spheres rotating in the heavens. For such empirical knowledge, cognition must conform to the world. The world will not have fairies in it just because we believe in fairies, nor will it cease to have molecules if we cease to (or do not yet) believe in molecules. Kant's Copernican turn justifies the possibility of some substantive a priori knowledge of the world, but it does not justify claiming to know everything about the empirical world simply by reflecting on one's cognitive capacities.

But Kant also argues that the distinction between intuitions and concepts (and relatedly between sensibility and the understanding) provides for the possibility of a priori knowledge that goes beyond mere conceptual analysis. Even human receptivity has an a priori structure to which the world must conform, and so there can be an a priori science of the principles of this sensibility. Moreover, precisely because sensibility is a faculty of intuitions rather than of concepts, an a priori science of sensibility will not proceed simply by unpacking concepts, and thus may provide a way of justifying claims that are both a priori and synthetic. In particular, Kant argues that space and time are a priori intuitions that structure all humans' empirical intuitions. We can neither think of the world as non-spatial or non-temporal nor think of external objects without an already-given spatial (and temporal) structure (A22–25/B37–40, A30–32/B46–48). And given space and time as a priori intuitions, Kant can explain the success of geometry (based on space) and arithmetic (on time), both of which give synthetic a priori knowledge (A25/B40–41).

Human understanding, like sensibility, has an a priori structure, and after a lengthy, detailed, and controversial defense of a set of a priori “categories” of thought,2 Kant turns to the way in which these two different cognitive faculties work together to structure the world of experience. By showing how humans' a priori categories work with sensibility to structure the empirical world, Kant's “system of all principles of pure understanding” provides the a priori metaphysics promised in his Preface. The specific details of the various ways in which these faculties combine are both complicated and contested, but one example (Kant's best known) is sufficient to give a sense for his general strategy. Kant defends the principle of cause and effect as one by which human beings structure the objective world: “All alterations occur in accordance with the law of the connection of cause and effect” (B232). Humans experience a changing world, so Kant's argument considers what is necessary in order for a set of perceptions to be considered perceptions of alteration (or, more generally, of something happening). Kant distinguishes merely subjective perceptions from objective experience. To have objective experience, one must organize perceptions in accordance with categories. But to have experience of objective alteration (succession), perceptions must be ordered in accordance with the category of cause–effect. If ordered using another category of connection (say, object–property or part–whole), the sequence of one's perceptions would not refer to an objective sequence, since objectively, one supposes that the properties of the thing exist at the same time as the thing and one supposes all the parts of a thing to exist at the same time. As an example of a purely subjective sequence, Kant describes the perception of a house, starting with the chimney, then the roof, then the windows, then the door. Here one does not suppose that objectively speaking there really is first a roof, then windows, then a door, and so on. By contrast, Kant gives the example of a boat, where one perceives a boat upstream, a boat midstream, and a boat downstream. Here one supposes not that these are different parts of a complicated stream-wide boat, but that in reality – that is, objectively – the boat is moving. Kant then considers what sort of concepts one would have to impose on one's set of perceptions to order them in such a way that one considers their order objective. His answer is that the perceptions would have to be thought of as though they ha...