This is a test

- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This volume is a comprehensive collection of critical essays on The Taming of the Shrew, and includes extensive discussions of the play's various printed versions and its theatrical productions. Aspinall has included only those essays that offer the most influential and controversial arguments surrounding the play. The issues discussed include gender, authority, female autonomy and unruliness, courtship and marriage, language and speech, and performance and theatricality.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Taming of the Shrew by Dana Aspinall, Dana Aspinall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literatura & Crítica literaria. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I.

A Critical History of The Taming of the Shrew

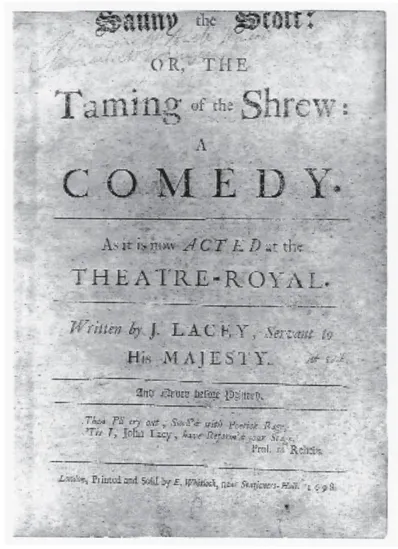

Figure 1. Title page from John Lacey's Sauny the Scot: Or, The Taming of the Shrew, 1698. Used with the permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Figure 2. Petruchio holding Kate's arm, saying, “But for my bonny Kate, she must with me” (3.2.216). Painted by Francis Wheatley, engraved by H. Partout. Used with the permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

The Play and the Critics

DANA E. ASPINALL

As with nearly every Shakespeare play, culturally and politically informed scholarship on The Taming of the Shrew has flourished over the past forty years. Arising from this scholarship and virtually unique to Shrew, however, are two matters of great interest (and some consternation as well) for the play's readers and audiences. First, even the most cursory of research into Shrew criticism reveals that much discussion of the play assumes a cultural or political bent from the start. The reason behind this is obvious: Katherine's final speech, where she urges the “foul contending rebel” wives—both those on stage and in the audience or reading the text—to “seek for rule, supremacy, and sway” from their “honest” husbands. Since its first appearance some time between 1588 and 1594, Shrew has elicited a panoply of heartily supportive, ethically uneasy, or altogether disgusted responses to its rough-and-tumble treatment of the “taming” of the “curst shrew” Katherine, and obviously, of all potentially unruly wives.

Second, and closely related to the first matter, a great deal of the more recent scholarship generally confines itself to a rather narrow range of issues beyond those implicit in Kate's final lines—the longest speech, incidentally, of the entire play. In Lena Cowen Orlin's estimation, only two primary issues outside Kate's capitulation (or ironic enactment of one, depending upon one's reading of the scene) concern us: “the relation of The Shrew to The Taming of a Shrew [and] the role of the induction” (167). Quite possibly, the debate concerning whether or not Katherine submits herself to Petruchio at the end of Shrew (and what this means to each succeeding reader or auditor) continues so heatedly that the other two issues are raised, as often as not, only as aids in determining a satisfactory interpretation of what transpires in act 5, including of course Petruchio's hearty response to it: “Why there's a wench! Come on, and kiss me, Kate.” Whatever the case may be, I believe Orlin correct in her observation and in further identifying each of these three issues as “vexed” (167).

In this volume of scholarship on Shrew, I attempt to map out, first in this introduction and then through my selection of the essays themselves, a chronological overview of the stipulations and qualities inherent in these three issues which so preoccupy and vex us. I include here scholars'continually evolving arguments involving gender relations and women's cultural and domestic roles, male fantasies of domination and control, female autonomy, genre, language and speech, privacy, and wealth, among other related issues. Much of Shrew's early publication and theater history also will be outlined, as well as a summary of some of the theories concerning the Induction's relationship to the main play. The introduction, I hope, will serve as a forum for those earlier critics whose comments either helped to shape the twentieth century's thoughts on these matters or have provoked some often strongly contradictory reactions to them. I also try to acknowledge and give voice to some of the many essays and commentaries not included in this volume, situating their arguments among those of the early critics and of the authors included. In short, I aim to provide a solid general foundation from which the essays in this volume will explore in much fuller detail as many treatments of the three issues as possible. Because Jan MacDonald's, Margaret Loftus Ranald's, Ann Christensen's, and Barbara Hodgdon's admirably thorough overviews of the stage, film, and screen productions of Shrew are included in the volume, I end the introduction's stage history with the advent of the twentieth century.

In all, I have selected for inclusion in this volume nineteen essays and reviews, each of which represents a major focus or change of thought concerning Shrew. In keeping with the speculation concerning offered above, I allow most space for the wide range of viewpoints inspired by the scene involving her final speech. It is here, I believe, that the play becomes most resonant in our own culture as we enter a new century of critical inquiry. This scene also seems to bring to the fore the most vexing issue of the three, for the arguments surrounding a wife's duties and behavior seem to shape not only the tones and strategies of the play's (and in some instances, perhaps more accurately, Petruchio's) supporters and detractors, but also are at least partially responsible for confining other examinations of the play to the two other issues mentioned above. Regardless of the particular issue at hand, moreover, the attention that Shrew perpetually garners with each generation of readers and theater-goers confirms most forcefully Annabel Patterson's claim that Shakespeare's “plays and poems seem to suggest, at some deeper level than we yet have a terminology for, that male/female relations in his environment were somehow imbricated with the sociopolitical relations supervised or represented by government and the law” (1994, 305).

Wherever I quote from The Shrew in the introduction, I have used David Bevington's edition of The Complete Works of Shakespeare, 4th edition (Harper Collins, 1992), and where I quote from A Shrew, I have used the Mal-one Society facsimilie edition (Oxford, 1998). I also have relied heavily on, and owe much gratitude to, past editors of Shrew and Shakespeare for many of the facts, dates, and conjectures included in my introduction: Bevington, Bond, Capell, Dolan, Evans, Hanmer, Johnson, Malone, Morris, Oliver, Pope, Quiller-Couch and Wilson, Rowe, Theobald, Thompson, Warburton, and Wright, among others. I also have included a bibliography of other essays pertaining to Shrew for further reading.

EARLY PUBLICATION HISTORY OF SHREW

The dates surrounding Shrew's early textual and stage history create more questions than they answer, simply because we do not know whether we are piecing together the facts concerning one, two, or possibly even three different plays. Furthermore, we can only guess at the relationships between any one of these Shrew plays and the others. The plays in question, in order of their appearance to scholars devoting time to studies of them, consist of the following: (1) A Pleasant Conceited Historie, called The taming of a Shrew, which first appeared in quarto in 1594; (2) The Taming of the Shrew, which was included in the 1623 First Folio, and (3) a lost play that may or may not have existed and that may or may not be a source for one or both the 1594 and 1623 Shrews. Theories surrounding these plays are varied and, in Richard Hosley's words, “can be explained equally well by the one theory as by the other” (1964; 291). From this morass of conjecture emerge, however, three generally accepted postulates: the 1594 text (hereafter referred to as A Shrew) is a source for the 1623 text (hereafter The Shrew); A Shrew is a “bad” quarto—either a memorial reconstruction or an “imitation” (Wells and Taylor 1987, 351)—of The Shrew; or A Shrew is a bad quarto of the lost Shrew text, which also is the source for The Shrew. Currently, most scholars reject the first postulate (that A Shrew is a source of The Shrew) and lean toward the second (that A Shrew is a bad quarto of The Shrew). However, none of the theories presented above is accepted with any certainty. In fact, new—or at least newly reconfigured—theories abound, including Leah Marcus's recent argument that A Shrew ought to be accepted as a viable alternative to The Shrew, because, among other equally compelling arguments, some “of the most profoundly patriarchal language of The Shrew is not present in A Shrew” (1992; 185).

As Orlin has noted and the above summary of Shrew's several manifestations attest, issues surrounding the play vex us with both possibility and doubt. Let us now, for a moment, leave behind the uncertainty and turn to the facts we have. The first documented appearance, both on stage and in print, of Shrew was 1594. On May 2, to the publisher Peter Short, was entered in the Stationer's Register, “a booke intituled A plesant Conceyted historie called the Tayminge of a Shrowe” (Chambers 1930, 1:322). This text was produced again by Short in 1596, to be sold by the bookseller Cuthbert Burby at his shop in the Royal Exchange. On January 22, 1607, the rights to A Shrew were transferred by Burby to Nicholas Linge (Short had died in 1603, and the facts behind Burby's ownership of the rights are uncertain); during that same year, a third quarto of A Shrew was printed by Valentine Simmes for Linge. And on November 19, 1607, the rights were transferred again, this time to John “Smythick” (Smethwick). As far as we know, Smethwick did not publish A Shrew between the year of his acquisition of A Shrew and 1623, when a considerably different version appeared in the First Folio (Oliver 13–15).

This different version, of course, is The Taming of the Shrew, which shares the same three plotlines and most of the various intersections between its main plot and subplots: Kate's shrewishness and subsequent unmarriageability, the several rivals' wooing of Kate's sister—A Shrew provides Kate with two sisters, Emelia and Philema, and the “Induction,” so-named by Alexander Pope. Yet, The Shrew differs from A Shrew in several respects. These variances include the many name changes (except for Sly's and Kate's, all characters' names are different), length (A Shrew is only sixty percent as long as The Shrew and does not have the characters corresponding to Gremio or Tranio from The Shrew), and setting (A Shrew takes place in Athens, not Padua).

More importantly, the drunken tinker Christopher Sly (spelled “Slie” in A Shrew), who opens both versions of the play (although in slightly different apparitions), “disappears” from The Shrew at the end of act 1 scene 1 and is not heard from again. In A Shrew, Slie remains an intrusive presence throughout the play, even coming on at the play's end to announce, after watching Ferando's (The Shrew's Petruchio) complete subordination of Kate unto him:

I know now how to tame a shrew,I dreamt vpon it all this night till now,And thou hast wakt me out of the best dreameThat euer I had in my life, but Ile to myWife presently and tame her tooAnd if she anger me. (52, ll. 1619–24)

Slie's presence and his more frequent interruptions of the main plot throughout A Shrew provide this play with a completely closed frame; with such total closure, Thelma Nelson Greenfield (1954) and Alan C. Dessen (1997) have argued, A Shrew provides through Slie's final speech a “moral” that can—and, perhaps, will—be initiated on both the play's other wives and the actual wives watching in the audience or reading the text. Furthermore, if A Shrew is a source for, or a bad quarto of, The Shrew, then this moral may apply equally (or, perhaps, more stridently) to the 1623 printed version. The moral, of course, insists on the proposition that wives are bound in obedience and duty to their husbands' wills, and promises harsh mistreatment if wives break the bond.

SHREW'S POSSIBLE SOURCES AND ANALOGUES

Let us consider for a moment a possible consequence that the presence of this moral may obtain for the play's auditors and readers. First, in combination with A Shrew's altered lines in Kate's final speech—

The King of Kings the glorious God of heauen,

Who in six daies did frame his heauenly worke,

And made all things to stand in perfit co...

Who in six daies did frame his heauenly worke,

And made all things to stand in perfit co...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- General Editor’s Introduction

- Acknowledgments

- List of Illustrations

- Part I A Critical History of The Taming of the Shrew

- Part II The Taming of the Shrew: Critical Appraisals

- Part III The Taming of the Shrew on Stage, in Film, and on Television