1 Revisioning urban space and cityscapes

Christoph Lindner

URBAN NEOLITHIC

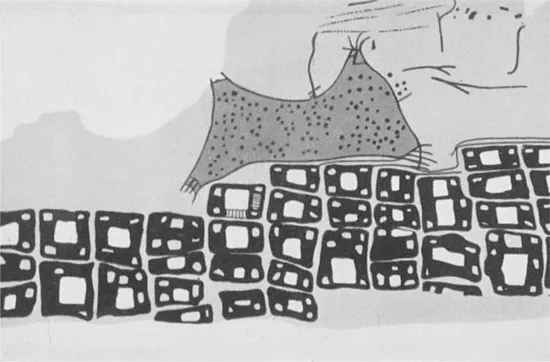

In his foreword to this book, Edward Soja cites a wall painting from the Neolithic settlement of Çatalhöyük in central Turkey as an important artistic breakthrough in urban culture. Showing a volcano erupting behind terraces of densely packed houses, the 8,000-year-old painting not only marks the emergence of specifically urban art, but also presents the earliest known panorama of an urban landscape. Commenting on the geohistory of cityspace in Postmetropolis, Soja elaborates on the significance of the Çatalhöyük mural, suggesting that this ‘original example of a distinctively and self-consciously panoramic urban art form… expresses a popular awareness of the spatial specificity of urbanism’ (Soja 2000: 40). When understood in Soja’s terms as a graphic record of the social production of urban space–one, moreover, that is rendered from a panoramic cityscape perspective–the Çatalhöyük mural resonates powerfully with the subject of this book. So much so, in fact, that further close analysis of the image brings into focus some of the key concerns underpinning the chapters that follow. As such, I would like to pursue a few additional speculations extending from Soja’s insights into Çatalhöyük.

Among the mural’s most distinctive features is the geometric abstraction of the built environment of the city. The evenly spaced houses are homogenized into nearly identical cubes, which in turn are stacked into larger, linear blocks. The negative space between the houses creates a grid of perpendicular lines. And the twin peaks of the towering volcano, which dominate the background of the mural, are composed of symmetrical triangular forms. For Soja, this ‘creatively cartographic representation of cityspace’ suggests an ‘egalitarian yet individualized built environment’ (Soja 2000: 40), a view that is supported by James Mellaart’s (1967) original archeological excavations of the site in the 1960s.

Yet, looking at the image from a twenty-first-century perspective, I cannot help but see certain aesthetic affinities between the cubed city of Çatalhöyük and any number of modernist pictorial representations of urban space, ranging from the early cubist compositions of Braque and Picasso to the industrial landscapes of L.S. Lowry, and even to some of Le Corbusier’s imaginative city sketches. It would be wrong, of course, to suggest that such affinities are anything but accidental, but it is none the less interesting to consider the possibility that the project of rationalizing urban landscape and architecture, which has dominated so much artistic and intellectual engagement with the modern city, was already an integral part of urban culture in the neolithic period.

Figure 1.1. Çatalhöyük: detail from reconstruction of volcanoscape (courtesy of James Mellaart/Çatalhöyük Research Project)

Gary Bridge begins his book Reason in the City of Difference by observing that ‘the city has always been the home of reason’ (Bridge 2005: 1). Çatalhöyük’s urban volcanoscape, which could be interpreted as a sort of gridded urban master plan, certainly appears to illustrate this point. Yet in its subtle evocation of an ‘individualized built environment’–suggested not only by the clear demarcation of each building’s boundaries but also by the slight variations in the size and appearance of the houses–the image also presents a register of difference. Difference is something that modern urbanism has often sought to pave over (sometimes literally), favouring instead an exclusive and homogenized ‘space of reason’ (Bridge 2005: 1). Reclaiming the place of difference within the discourse of urban rationalization is, as Gary Bridge argues, ‘central to current understandings of the directions of urbanism’ (Bridge 2005: 2). It is also a recurring concern for the contributors to this book. From the cartographic blind spots of postmodern Jakarta to the skyrocketing urban shoreline of Australia’s Gold Coast, many of the interstitial cityspaces examined in the following pages positively demand new critical and theoretical frameworks for conceiving and analysing difference.

The other striking feature of the Çatalhöyük mural is its vivid depiction of a volcanic eruption in process. The image shows fire exploding from the summit, lava flowing from the mountain base, smoke and ash choking the air, and pyroclastic debris hurtling through the sky. While the reason for including the eruption in the mural was almost certainly to mark the volcano’s economic status as a producer of obsidian (Mellaart 1967: 177), the presence of the towering inferno could none the less be read in a more sinister way as an emblem of violence and destruction. This idea is reinforced if we consider the volcano’s probable religious significance as a link to ‘the underworld, the place of the dead’ (Mellaart 1967: 177). This additional symbolic valence might further explain why the spectacle of volcanic eruption proved so captivating to the neolithic urban imaginary.

What I find particularly fascinating about this aspect of the mural is the explicit link it makes between violence and the city. In fact, with the absence of perspectival realism, depth in the painting is flattened to the extent that the volcano appears to be resting directly on top of–rather than behind–the houses. Viewed in this way, the volcano suddenly becomes an immediate threat to the city–no longer just a distant firework display. Given the volatile and often violent history of urban morphology, it is somewhat fitting–as well as just a little prophetic–that the world’s first cityscape painting should also contain the world’s first image of urban destruction.

In the last few decades, such images of the city have achieved a new pre-eminence in our global media culture. In addition to natural disasters like the Mexico City and Kobe earthquakes, we have begun to experience a surge in images of other, man made forms of urban violence such as inner city race riots, gang warfare, and sectarian violence. The decades around the turn of the millennium have further witnessed a growing number of terrorist explosions in buildings and public spaces in cities throughout the world, including Barcelona, Beirut, Casablanca, Istanbul, London, Madrid, Manchester, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Omagh, Paris, Riyadh, Rome, Tel Aviv, and Washington, DC. While this sort of violent politicization of urban space is by no means a development unique to the present age of globalization, it has arguably acquired a new, heightened significance in the aftermath of 9/11. Never before have cityscapes and cityspaces occupied such a prominent and symbolically charged place in political, critical, and cultural debate. It is not surprising, therefore, that the relationship between violence and the city–a link established pictorially some 8,000 years ago on the high plains of Anatolia–is another of this book’s key concerns, informing chapters on topics as diverse as the cinema of urban disaster, the architectural redevelopment of Ground Zero, the psychogeography of underground Paris, and the virtual landscape of post-war Berlin.

URBAN GROUNDSWELL

The extent to which urban space and cityscapes continue to engage our cultural imagination in the twenty-first century was exhibited in a quite literal way at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 2005. Following several years of major redesign and reconstruction–an architectural project which in itself sought to reinforce the spatial connections between the museum and the surrounding cityscape (Figure 1.2)–the MoMA reopened with a series of innovative exhibitions that included a showcase of contemporary landscape design entitled ‘Groundswell’. The idea behind ‘Groundswell’, as the exhibition’s curator explains, was to portray ‘the surge of creativity and critical commentary surrounding contemporary created landscape’ (Reed 2005: 15). To this end, the exhibition offered an international survey of constructed landscapes ranging from reinterpretations of public parks, walkways, and plazas to reimaginations of industrial wastelands and coastal landfills. Significantly, all twenty-three of the projects featured in the exhibition are either located within or directly linked to cities. In other words, what the exhibition placed on display were not just constructed landscapes, but specifically urban forms of constructed landscape–forms reclaimed from or generated by the wide array of transitional open spaces (such as parking lots, rooftops, and bomb sites) contained within contemporary cities. Each of these projects, moreover, shows an attentiveness not only to the transformative potential of urban space, but also to the ways in which that space relates to a wider cityscape.

Figure 1.2. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2005, designed by Yoshio Taniguchi: exterior view (© The Museum of Modern Art/Scala, Florence)

In the case of the Schouwburgplein (Theatre Square) project in central Rotterdam, for example, the conventionally static space of the public square is redesigned as an active stage for outdoor events conceived to consolidate the nearby performance spaces of the municipal theatre, cinema, and concert hall (Figure 1.3). However, the design is also intended to encourage public participation in spontaneous performative activities. To enable this, the square incorporates a row of towering, coin-operated hydraulic light masts, creating ‘a sort of kinetic sculpture recalling the steel cranes that unload shipping containers’ (Reed 2005: 34). During the day, these oversized industrial lamp-posts perform an improvised ‘mechanical ballet’ (Reed 2005: 34). At night, they illuminate the space, casting circles of light around the square. The overall effect is not only to enliven the form and function of the public square, but also to bring the space itself into dialogue with the city and its inhabitants.

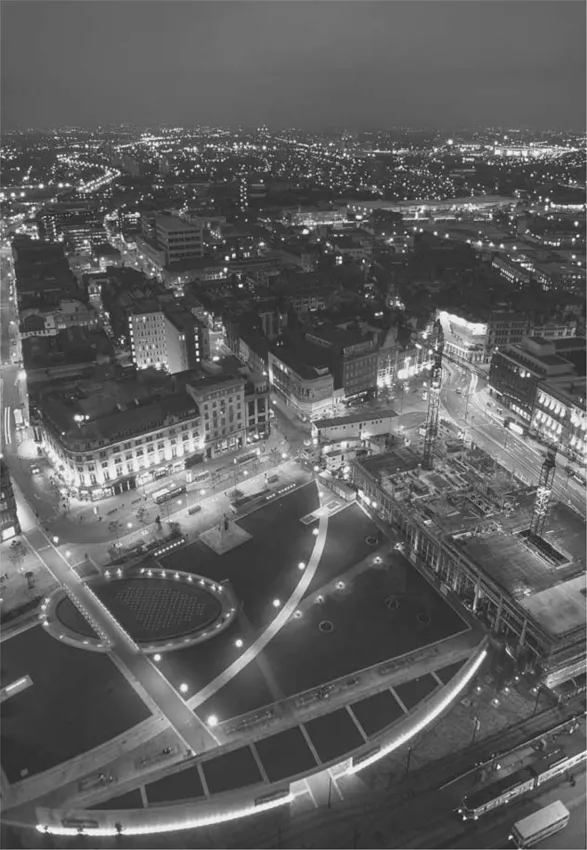

A similar concern for the interrelation of city and public space underlies the redevelopment of Piccadilly Gardens in Manchester (Figure 1.4)–another of the constructed landscapes featured in ‘Groundswell’. The main challenge facing this project was to contribute to the regeneration of Manchester city centre in the aftermath of the 1996 IRA bombing, which destroyed over a million square feet of retail and office space. The related challenge was to reclaim green space from the city’s growing transport infrastructure in such a way as to facilitate pedestrian use while also maintaining a smooth flow of traffic around the site (see Parkinson-Bailey 2000: 268). One of the most interesting aspects of the final design is the way it incorporates the form and flow of a city street into the park itself. Extending in an uninterrupted straight line from the adjoining road, a pedestrian thoroughfare cuts across the width of the park. Intersecting this thoroughfare at a right angle is another walkway that gently arcs to connect the far corners of the park. The result is a blurring of the distinctions between urban pavement and garden path–a nearly seamless transition that invites pedestrians to stray into the park from the city as well as back into the city from the park. In this respect, the design successfully reconnects Piccadilly Gardens with the city centre by plugging the park’s walkways directly into a much larger and more complex city-wide network of human traffic.

Figure 1.3. Rotterdam: Schouwburgplein at night (courtesy of West 8 Landscape Architects)

Figure 1.4.Manchester: Piccadilly Gardens at night (courtesy of EDAW, photo by Dixi Carrillo)

But perhaps the most poignant engagement with urban space and cityscapes in ‘Groundswell’ comes from one of the exhibition’s least obviously urban projects: the Fresh Kills ‘Lifescape’. Due to start construction in 2007, ‘Lifescape’ is an ambitious plan to transform the 2,200 acre Fresh Kills landfill on the edge of New York City into an eco-friendly park, complete with wetlands, grasslands, woodlands, playing fields, pedestrian and bicycle paths, and even a wildlife reserve. Interestingly, the design envisions retaining much of the artificial topography created by the undulating mounds of garbage, some of which reach heights of over 200 ft. These mounds will be sealed beneath a protective polymer lining and topped by a thick layer of soil, enabling the ecological and environmental recovery of the site. On the surface, therefore, ‘Lifescape’ will be a vibrant natural landscape–an idea reinforced by the word ‘life’ in the project title. Underlying this natural landscape, however, will be the cumulated waste of one of the world’s most excessive cities. So while ‘Lifescape’ will appear at first to be disconnected from the city–and, indeed, the parkland is partly conceived to offer an escape from urban space–the landscape will none the less remain intimately and inextricably connected to the city at a much more fundamental level. In a very real way, this rehabilitated natural landscape will be shaped and sustained by a hidden cityscape of urban waste.

It is also worth noting that the Fresh Kills landfill is the final resting place of the World Trade Center towers. Following the terrorist attacks of 9/11, the wreckage from Ground Zero was transported to the landfill, which was specially reopened to accommodate the 1.2 million tons of material. The ‘Lifescape’ design commemorates the Twin Towers with an earthwork monument formed by two inclining landforms that mirror the exact shape of each skyscraper laid on its side. In a further commemorative gesture, the monument is oriented on an axis with the skyline where the towers originally stood, allowing a panoramic vista of lower Manhattan in the far distance–a view soon to include the distinctive profile of the Freedom Tower rising from the redeveloped WTC site.

The earthwork monument accordingly establishes another strong link back to the lived space of the city. The orientation of the monument creates a direct visual connection with the New York skyline, encouraging visitors to gaze at the city from the vantage point of its recycled dumping ground. Meanwhile, the shape of the monument evokes the origins of the urban wreckage contained in the ground beneath, transforming the softly sculptured landscape into a kind of grave–a burial mound for the material remains of the urban superstructures that once stood as the world’s most prominent and emblematic icons of capitalist globalization. As such, the 9/11 earthwork monument simultaneously conceals and reveals the mutability of urban landscape. And, like the ‘Lifescape’ project as a whole, the monument also attests to the extraordinary versatility of urban space and the imaginative ways in which it can be recycled, renewed, and remade.

The title of the ‘Groundswell’ exhibition suggests a burgeoning of innovation and creative production within contemporary landscape architecture and urban design. Projects such as Rotterdam’s Schouwburgplein, Manchester’s Piccadilly Gardens, and New York’s Fresh Kills ‘Lifescape’ certainly support such a view in the way that each seeks not only to reclaim but also to reinvent a particular city space. For Peter Reed, MoMA’s Curator of Architecture and Design, such ‘palliative spaces’ are ‘causes for optimism’ because of the contribution they make to ‘the quality of civic life’ and the role they play ‘as catalysts for urban development’ (Reed 2005: 16). It is hard not to share Reed’s sense of optimism when surveying the exhibition’s full range of regenerative landscape projects, including such radically transformative designs as Hadiqat As-Samah (Garden of Forgiveness) in post civil-war Beirut and the Parc de la Cour du Maroc in the post-industrial train yards of Paris.

Yet, looking at urbanism from a wider array of historical, critical, and disciplinary perspectives, this book finds that the cultural significance of urban space and landscape is arguably more complex, contested, and unsettled than Groundswell’s necessarily select survey is able to make evident. Drawn from the fields of cultural theory, architecture, film, literature, visual art, and urban geography, the chapters in this volume make a collective, cross-disciplinary case for the continuing importance of questioning cities–including their causes for social optimism. In making this case, the contributions offer what I am hopeful readers will see as another kind of groundswell: not just a surge of creative urban production but also a burgeoning of innovative critical urban analysis drawn from across the humanities, social sciences, and beyond.

IMAGE–TEXT–FORM

Connected by a shared concern for issues of spatiality, the chapters in this book are organized around three broad, interrelated themes–image, text, and form–and range from the examination of cyberpunk skylines, postcolonial urbanism, and the cinema of urban disaster, to the analysis of iconic city landmarks such as the Twin Towers, the London Eye, and the Jewish Museum Berlin. The first part of the book, ‘Image’, focuses on imaginary, visual, and spectacular representations of the city. The second part, ‘Text’, contains chapters concerned with textual, intertextual, and other discursive treatments of urban space. And the final part, ‘Form’, contains chapters investigating the ways in which space and form intersect in the city.

In the opening chapter of Part I, Mark Dorrian considers how the world’s first Ferris wheel, constructed for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, instigated a new way of seeing and experiencing cityscapes. As Dorrian argues, this specifically urban panoptic form, which has become such an integral part of the contemporary landscape of cities like London and Vienna, marks a turning point in the cultural history of the aerial view. Born of a late nineteenth-century culture of exhibition and consumption, George Ferris’s invention simultaneously functioned as a vantage point, a kinaesthetic device, and a new form of entertainment for the masses. For Dorrian, whose interests lie in the visual possibilities and effects produced by the wheel, the emergence of this giant ‘rotary eye’ comments forcefully on the ideological role of the aerial view within urban modernity, as well as on the cultural trajectory of the ‘hypervisual spectacle’. Dorrian concludes by speculating on the possible relationships between the Ferris wheel, proto-cinematic forms of still photography, and the production-line procedures for animal ‘disassembly’ that were pioneered at Chicago’s Union Stock Yards in the years leading up to the 1893 Exposition.

Moving from the late nineteenth-century proto-cinematic flickerings explored by Dorrian to the full-blown scopic sensations of twentieth-century film, Barry Langford’s chapter focuses on the representation of urban disaster in apocalyptic cinema. In particular, Langford draws on Michel de Certeau’s thinking about urban voyeurism and imagined disaster to stage a series of strategic encounters between urban theory and urban film. Arguing for the importance of rethinking the function of fantasy and play in cinema’s post-apocalyptic urban visions, Langford deciphers the ruined cities of films ranging from Hollywood blockbusters like Deep Impact (1998) and The Day After Tomorrow (2004) to European art-house productions like Jacques Tati’s Playtime (1967) and Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire (1987). The result is not only fresh insight into the strangely morbid fascinations of cinema culture but also a renewed understanding of de Certeau...