This is a test

- 252 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Antony Kamm presents an accessible, user-friendly introduction to the people of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah from earliest times up to AD 135.

Charting the history of the Israelites, Kamm discusses their origins, land, society, culture and religion, as well as their relationship to the Roman world and their legacy. An appendix provides:

* a chronology

* the Hebrew alphabet

* weights, measures and coins

* the Jewish calendar

* a guide to further reading for easy reference.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Israelites by Antony Kamm in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1

THE ORIGINS OF THE

ISRAELITES

It is with the patriarch Abraham, in about 1800 BCE, that the story of the Israelites properly begins, though it is at the time of Moses and the Exodus from Egypt that they first emerge as a people with an identity.

Abraham was descended from Shem, one of the sons of Noah (Gen. 11:10ff.). Shem’s descendants, known as Semites, correspond to the ethnic and linguistic groups of the Mesopotamian Fertile Crescent and its immediate surroundings – the term Semite today embraces peoples of the Middle East and northern Africa who originally spoke the related languages of Aramaic, Akkadian, Arabic, and Ethiopian, as well as Hebrew.

When Abraham, following the instructions of his God, set out from Haran, on the northern edge of the Fertile Crescent, with his wife Sarah and his extended family, to journey on foot to the land of Canaan, the Middle Bronze Age was under way.

At that time northern Britain was occupied by the ‘Food Vessel’ culture: the people of the brilliant Wessex culture in the south were traders and builders, and were responsible for restructuring the religious monuments of Stonehenge into the form in which they appear today. On the island of Crete in the Mediterranean Sea, the Minoan civilisation was already in its middle phase.

There had been dynastic rulers in Egypt for over a thousand years. The Great Pyramids and the Sphinx were already six hundred years old. Egyptian astronomers had worked out a solar calendar of 365 days. There was a literature of Egyptian prose and verse, recorded in hieroglyphics. Egyptian doctors had a surgical textbook comprising forty-eight case studies, which may have been written down as early as 3000 BCE.

The Egyptians probably got the idea of writing from the Sumerians, with whom there is evidence of a lively cultural exchange. The Sumerians are the earliest recorded inhabitants of the eastern wing of the Fertile Crescent. Between 2850 and 2360 BCE they controlled an empire of about a dozen independent city-states, each ruled by a king. The most notable of these were Ur, Erech, and Kish, though in each case the city itself would be in modern terms no larger than a substantial village, perhaps three-quarters of a square mile in extent.

The religious beliefs of the Sumerians, which can be traced back to the fourth millennium BCE, embraced a pantheon with an elaborate structure, mythology, and philosophy. Their writing (cuneiform) was inscribed on tablets of clay with a stylus in horizontal lines reading from left to right. A very early clay tablet, discovered at Nippur, records a mythical deluge which has close affinities with the Biblical Flood. There are further parallels with the flood narrative in the Akkadian epic of the legendary king of Erech, Gilgamesh, which dates from the beginning of the second millennium BCE. The earliest written version of the Gilgamesh epic that we have was inscribed between 1750 and 1400 BCE. It could well have been transmitted to Canaan in this or in oral form by ancestors of the Israelites.

In about 2300 BCE, the Akkadians, under their dynamic ruler Sargon, defeated the Sumerians and created their own empire, which lasted until 2180 BCE, when it was destroyed by waves of Gutians from the mountains of the north-east. Though Akkadian survived into the first millennium BCE as the language of international diplomacy and trade, the Sumerian civilisation emerged from these invasions in better shape, with Ur briefly becoming a considerable power in its own right – the famous ziggurat of Ur was built during this period. In about 1950 BCE Ur too fell, to an Elamite invasion. Though centres of wealth and culture continued to exist, with commercial links between them, it was an age of consistent turmoil and uncertainty, of hostile incursions, and of huge movements of nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples throughout the whole region of what is now Asia Minor, the Caucasus, and the Middle East. In such circumstances there is nothing unusual about the mere fact of Abraham’s journey from Haran to Canaan, or even an earlier migration (Gen. 11:31), in the company of his father, from Ur to Haran.

The 800-mile trek between Ur and Haran took travellers for most of the way through fertile or pastoral country alongside the river Euphrates. There was an alternative route in regular use, along the river Tigris. The two cities were linked through trade, and also through religious observance: both were centres of the cult of Nanna, the Mesopotamian moon god. Nanna was the son of Enlil, lord of the air, who had forced his attentions on a young goddess called Ninlil while she was bathing in a canal.

Trade routes connecting all parts of the Fertile Crescent had been established at least as early as the beginning of the third millennium BCE by the city-state of Ebla in Syria, through whose territory the first stage of Abraham’s journey would take him. The archaeological site of Ebla was discovered in 1964. Its royal archive of fifteen thousand tablets inscribed in cuneiform revealed evidence of diplomatic and economic relations with eighty kingdoms. The most notable of these was Asshur, which subsequently gave its name to Assyria. The Eblaites employed the Sumerian system of writing, but their language proved to be a hitherto unknown Semitic form. It was superseded in about 2000 BCE when a new, Akkadian-speaking, Amorite dynasty succeeded the ancient one in Ebla.

AMORITES AND ARAMAEANS

In all the historical comings and goings, the Amorites are the people most frequently referred to. Their name, written in cuneiform as Amurru, means ‘Westerners’, a reference to their settlements in northwestern Mesopotamia and northern Syria, to which they had migrated from their original homelands in the Arabian Desert. They were not so much a racial entity as a collection of peoples speaking a variety of Semitic dialects. When Ur finally fell, Amorites poured into the area, appropriated most of the ruling positions, and adopted the Akkadian/ Sumerian cultures that they found. They also overflowed into Canaan, and it is not improbable that Abraham’s mission coincided with one of these incursions.

The Biblical Aramaeans were descended from Aram, who, like his great-uncle Abraham, was a descendant of Shem (Gen. 10:22). Abraham’s son Isaac married his cousin Rebekah, daughter of Bethuel ‘the Aramean’ (Gen. 25:20). Isaac’s son Jacob married Leah and Rachel, daughters of Laban ‘the Aramean’ (Gen. 31:20, 24), Rebekah’s brother (Gen. 24:28). An enigmatic passage in Deuteronomy (26:5) refers to a patriarch as a ‘fugitive [NEB ‘wandering’ or ‘homeless’] Aramean’.

A Biblical Aramaean pedigree for the Israelites is thus inescapable, but the historical Aramaeans do not appear on the scene until about 1100 BCE, as a collection of tribes in northern Syria who ultimately established a state centred on Damascus. Two explanations have been offered for the Aramaean ancestry of the Israelites. The first is that the patriarchal Aramaeans were Amorites of ‘proto-Aramaean stock’. The second is that the use of the name is a conscious anachronism introduced into the Biblical account at the end of the second millennium BCE, at a time when the patriarchal homeland of Haran was in a region occupied by the Aramaeans. In the same way we use terms such as Middle East or Syria to describe regions or areas in the ancient world. A similar argument has been used to explain ‘Ur of the Chaldeans’ as Abraham’s birthplace (Gen. 11:28; 15:7) – the historical Chaldeans, who appear to have had Aramaean affiliations, occupied the southern part of Babylonia in the eleventh century BCE.

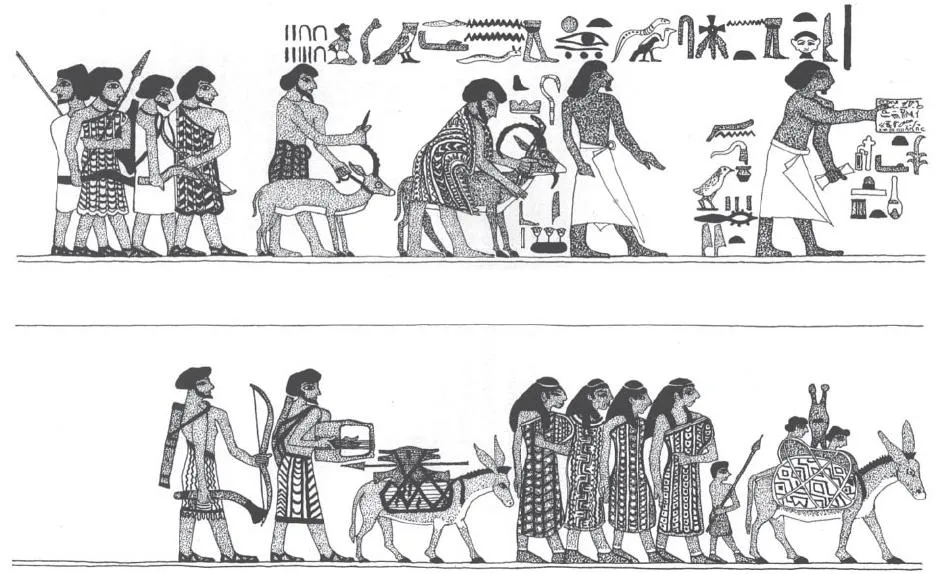

Figure 1 Detail of a wall painting, in colour, from the tomb of Khnumhotpe, overseer of the eastern desert region of Egypt, at Beni Hasan. Dated to approximately 1890 BCE, that is about or just before the time of Abraham, it shows a group of Semitic nomads from Canaan, eight men, four women, and three children, being presented by two Egyptian attendants, one of whom holds up a document with their details. The leader of the group is bending over a gazelle; the next man holds the horn of an ibex. The warriors are armed variously with bows, spears, curved swords, and (the man at the rear) an axe of the duckbill type of the Middle Bronze Age. The man one from the rear carries a lyre, and has a skin water bottle on his back. The two curiously shaped objects on the donkeys’ backs have been identified as goatskin bellows, such as were used by metal-workers. The men wear embroidered kilts or tunics which are predominantly red. The longer tunics of the women are patterned in red, blue, and yellow. The two leading men are barefoot. The rest of the men wear sandals, but the women and the boy have skin boots. The various signs and symbols are Egyptian hieroglyphs, each representing a word or a sound value.

NOMADS

Abraham and his kin were semi-nomads, to whom Haran was the homeland to which one returned to find a wife. So Abraham in due course despatched his aide Eliezer from Canaan to seek a suitable partner for his son Isaac (Gen. 24). Isaac’s son Jacob, after deceiving his twin brother Esau, was sent back to Haran to be out of the way, and urged to seek a wife there rather than marry a Canaanite (Gen. 28:1).

The way of life of these nomads can be reconstructed from contemporary texts such as those in Akkadian found at the Amorite centre of Mari. They bred sheep, usually of the white, fat-tailed variety, black goats, and small cattle, and used donkeys to carry their baggage and tents, and food and water. The animals fed off the land, and needed to be moved on when supplies were exhausted. Stops were sometimes long enough for crops to be sown and harvested, and even for small village settlements to be established. There was a hierarchical structure, based on the family: extended families or clans were grouped into tribes, supervised by a tribal confederacy.

There is a glimpse of a nomadic band on the move in the Egyptian semi-autobiographical narrative known as The Tale of Sinuhe, which can be dated almost precisely within the few years after 1960 BCE. Fearful of a court plot to kill him, Sinuhe escapes on foot towards Canaan. On the way,

I collapsed from thirst, utterly dried out. My throat was on fire with the taste of death. Then a glimmer of hope! I heard the lowing of cattle. Some nomads came in sight. Their leader had been in Egypt and recognised me. He gave me water, and boiled some milk for me, and then took me to his clan. They were very kind to me.

Travel writing is a comparatively modern literary genre. Vast distances were covered in the ancient world without anyone bothering to describe what it was like to be the traveller. While the journey from Haran to Canaan was shorter by some 200 miles than the one from Ur to Haran, the conditions would have been very different, involving desert and mountain terrain. Much of the rest of the going would have been across rugged ground, covered with boulders and sparse scrub. The ‘wild beasts’ referred to in Exodus 23:11 and elsewhere in the Bible are likely to have included the Palestinian lion, the Syrian brown bear, wolves, hyenas, jackals, scorpions, and several species of snake, of which today at least thirty-five are extant in the region. ‘The ambuscade of bandits who murder on the road to Shechem’ (Hosea 6:9) must have been a perpetual hazard and a continual fear for travellers.

Travel conditions are unlikely to have deteriorated between the age of the patriarchs and 1481 CE, when Meshullam of Volterra, an Italian rabbi, travelled to Palestine and back in fulfilment of a vow. He wrote in Hebrew an account of his journey. The caravan which he was due to accompany from Gaza to Jerusalem, along a route which at some point must have been crossed by Abraham, was delayed by a bandit scare until it could muster a strength of at least 4,000 men.

From Gaza to Jerusalem is all desert. Every man must carry on his horse or donkey a sack of biscuits and one of straw and fodder, as well as water skins, for there is only salt water on the way. You must also take a supply of lemons. Lemon juice is the only remedy for insect bites. These reddish insects are the size of two flies. Lemon juice prevents the bite getting infected. I was never in my life in such pain as I was one night. You have to travel slowly. For one thing, there is so much dust and sand that horses can sink up to their knees. Also the dust rises and gets into your mouth, so that you can die of thirst. If you survive all this and your horse does not die on the way, there are other hazards. Lying in wait along the trail are men hidden up to their neck in the sand. They put a stone in front of them so that they can observe but cannot themselves be observed. When they see a likely caravan coming, they dig themselves out and call the rest of the band, who are mounted on horses as swift as leopards and have bamboo lances tipped with iron.

THE HEBREWS

The God to whom Abraham responded in Haran was a completely new, and revolutionary, God, whose initial revelation was, ‘Go forth from your native land and from your father’s house to the land that I will show you. I will make of you a great nation . . .’ (Gen. 12:1ff.). To those of the Jewish faith, or of similar thinking, divine–human communication is possible and has occurred. Others may prefer to believe that Abraham, understanding, through some form of religious experience, that he had been called by God, journeyed to Canaan to find a new home and establish there the worship of the true God; in the same way and with the same purpose, the Pilgrim Fathers sailed across the Atlantic to New England in 1620 CE.

Once in Canaan, Abraham’s clan moves by stages, as is the manner of nomads, from Shechem to a spot between Bethel and Ai (to stop near a town was common practice), and then to the Negeb. They see out a period of drought and famine in Canaan by going to Egypt (as was usual in difficult times), and then return to the Negeb.

After going on to Mamre, the normally peaceable Abraham is nettled into taking violent action. He leads 318 of his followers against some bandit kings, kidnappers of Abraham’s nephew Lot, who has opted out of the nomadic lifestyle to settle in the area of Sodom and Gomorrah. At this point (Gen. 14:13) Abraham is referred to as a ‘Hebrew’. From a strictly Old and New Testament standpoint, the Hebrews became known as Israelites, and then as Jews. The historical Hebrews, however, constituted a social stratum of stateless nomads known to the Akkadians as Habiru and the Egyptians as ‘Apiru, who were found all over western Asia at the time of the patriarchs and for several hundred years afterwards. In times of difficulty they might hire themselves out as mercenaries, or even as slaves. It could be said that the Israelites who eventually emerged out of Egypt under the leadership of Moses were all also ‘Hebrews’, but that not all the Hebrews who began the epic journey were Israelites.

At some point the fortunes of the Hebrews were affected by the activities of the Hyksos, a name from the Egyptian which means ‘rulers of foreign lands’. A portmanteau people of Semitic and Indo-European origins, the Hyksos employed their secret weapons, the warchariot, bronze protective armour, and composite bows which had a greater range than those of their enemies, to such purpose that in about 1720 BCE they successfully invaded Egypt, and for the next 170 years dominated the northern part of the land itself, establishing a capital and a ruling house at Avaris. The invasion was mounted from Canaan, which the Hyksos occupied during the eighteenth and seventeenth centuries BCE. At other times between about 2000 and 1250 BCE Canaan was controlled by Egypt.

GOD’S COVENANT

The promise that God subsequently makes to Abraham as chief of his clan is as crucial to the subsequent history of the land of the Israelites as it is to that of the Israelites themselves. ‘To your offspring I assign this land, from the river of Egypt to the great river, the river Euphrates’ (Gen. 15:18); the inhabitants of the land, among them the Canaanites, Amorites, Hittites, and Jebusites, go with the territory. The bond is sealed in a ritual manner (Gen. 15:9ff.), involving cutting sacrificial animals in two and passing between the halves, which recurs in Jeremiah 34:18–19.

The undertaking is repeated, on the first of many occasions, in Genesis 17, where Abraham is further promised unlimited offspring – the twin blessings of land and descendants were prized above all by those who depended on pasture for their livelihood. As a sign on the part of the human participants in the Covenant, every male is to be circumcised. This ritual, widely practised then and now, especially in desert regions, is to be performed on the eighth day after birth. Circumcision is the symbol of participation in the Covenant that God made with Abraham. While traditionally it continues to be maintained among Jews, it is not, except for converts to Judaism, obligatory, as it is for Muslims. To be Jewish, it is generally speaking enough for a child to be born of a Jewish mother.

The Hittites appear in Genesis 15 and elsewhere in the Bible as inhabitants of Canaan. From them Abraham purchased the burial site (Gen. 23:3ff.), in which were also interred his nearest and dearest, including his grandson Jacob. Esau, Jacob’s elder twin, had two Hittite wives (Gen. 26:34). The historical Hittites, however, were an Indo- European people who in about 2000 BCE pushed into Asia Minor, where they found, and assimilated into their ways, the Hattian civilisation. While maintaining as a base their capital city of Hattushash, the Hittites participated aggressively in the subsequent regional movements of peoples, and their empire, for a brief period between about 1590 and 1525 BCE, incorporated Babylon.

The Jebusites, also listed as inhabitants of t...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- FIGURES

- CHARTS

- MAPS

- PREFACE

- 1. THE ORIGINS OF THE ISRAELITES

- 2. THE LAND OF THE ISRAELITES

- 3. KINGS AND PROPHECIES

- 4. THE TWO MONARCHIES

- 5. THE ISRAELITES: SOCIETY, CULTURE, RELIGION

- 6. THE JUDAEANS: BABYLONIAN EXILE 586–538 BCE, AND THE PERSIAN YEARS 538–332 BCE

- 7. JUDAEA: HELLENISTIC AND HASMONAEAN YEARS 332–63 BCE

- 8. THE JEWS AND THE ROMAN WORLD 63 BCE–135 CE

- 9. LEGACIES OF THE ISRAELITES

- APPENDICES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY