This is a test

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Music in Ancient Greece and Rome

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Music in Ancient Greece and Rome provides a comprehensive introduction to the history of music from Homeric times to the Roman emperor Hadrian, presented in a concise and user-friendly way. Chapters include:

* contexts in which music played a role

* a detailed discussion of instruments

* an analysis of scales, intervals and tuning

* the principal types of rhythm used

* and an exploration of Greek theories of harmony and acoustics.

Music in Ancient Greece and Rome also contains numerous musical examples, with illustrations of ancient instruments and the methods of playing them.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Music in Ancient Greece and Rome by John G Landels in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1

MUSIC IN GREEK LIFE, POETRY AND DRAMA

Music played a very important part in almost every aspect of life for the ancient Greeks. It was heard at their public gatherings and at their private dinner-parties, at their ceremonies, both joyful and sad; it was heard at every act of worship, whenever people called upon, or prayed to, or gave thanks to the gods. It was heard in their theatres, whenever tragedies or comedies were staged, and on their sports grounds as the athletes competed. It was heard in their schools, on board their warships, and even on the battlefield. If ever a people had a just claim to be called music-lovers, it was the Greeks.

In reviewing their various musical activities, it will be necessary to make frequent mention of some of the instruments which were in general use. A detailed account of all the important instruments is given in the next chapter, but for the time being it will suffice to describe three of them very briefly:

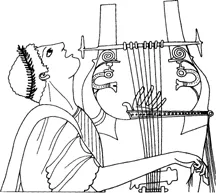

1) The kithara was a large wooden stringed instrument, played with a plectrum. It was supported by the left arm high in front of the player, who normally played standing. The instrument called phorminx by Homer and by some of the later poets was a forerunner of the kithara, similar in sound and function, but a bit smaller.

2) The aulos was a pair of pipes, with vibrating reeds in their mouthpieces, held out in front of the player.

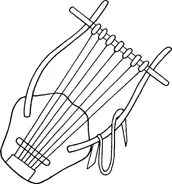

3) The lyre was a smaller stringed instrument, played in the same way as a kithara, but often held lower down – on the player’s lap if he was seated.

Music was never far away from the great religious festivals. The two most important Athenian ones, the Panathenaia and the Great Dionysia, were reorganized and expanded in the latter part of the sixth century BC, and in their developed form involved a great deal of music.

The Panathenaia was celebrated by the whole population of Athens and the surrounding district (Attica) in the summer of each year, with a special version, the Great Panathenaia, every fourth year. For that occasion a new robe was woven for the ancient statue of Athena, which was housed in the old temple, the remains of which are still visible on the Acropolis (the Erechtheum overlaps part of its foundations).

Figure 1.1 Kithara

Figure 1.2 Aulos

Figure 1.3 Lyre

The celebrations each year involved a grand singing procession which started near the boundary wall of Athens and wound its way all through the city, across the market-place (Agora) and up the slope of the Acropolis, accompanied by musicians and dancers. The musicians in the procession are conventionally represented in vase-paintings by two aulos-players and two kithara-players (there being no room for more figures) and in sculpture by four of each.1 These probably represent quite a large number of musicians, but it is difficult to be sure about this. There are very few references to large numbers of musicians playing ‘in concert’ earlier than the third century BC.

The nature of the music which was played and sung can be guessed. There was a type of song called apazan, which was most commonly sung in honour of Apollo, but could equally well be addressed to Athena. It is usually a solemn type of composition, expressing hope of deliverance from a dire peril, or as a thank-offering after escape. If it was sung on the occasion of a procession to the shrine of the god, it might be preceded or followed by a type of hymn called aprosodion, or processional, in which the god was invoked and praised; this was sometimes written in a different metre from that of the paian, but like the paian it was usually accompanied by a stringed instrument. The composition of Limenios, which is discussed in detail in Chapter 10, is in the form of a paian and prosodion.

It was also customary for musicians, usually aulos-players, to play while sacrifices were being offered, or any other solemn ritual was being carried out. As the Panathenaia involved numerous animal sacrifices, and every fourth year the changing of Athena’s robe, they must have been fully employed in this capacity. Moreover, apart from the strictly religious part of the festival there were competitive musical contests of all kinds, involving instrumental soloists, solo singers and choral singers and dancers. In fact, throughout most of the festival days the sound of music must have been almost continuous.

The other major Athenian festival, in which music featured even more prominently, was the Great Dionysia, held annually in late March or early April.2 This was the time of year when the sea became navigable after the winter storms, and things in general ‘opened up’.

The festivities occupied several days, and included a number of musical events. The most important ritual involved carrying a very ancient image of the god Dionysos in procession to the boundaries of the ancient Athenian territory and ‘welcoming’ him once more; this was intended as a gesture of apology for the fact that his original entry had been greeted with less than full enthusiasm. The statue was then carried back to his sanctuary in Athens (which was at the rear of the stage buildings of the theatre) to the accompaniment of ribald songs, reflecting the fact that it was in part a fertility ritual. All this would involve a lot of music.

When the procession returned to the city centre there were a number of musical events – competitions in aulos-playing, kithara-playing and singing; the only entertainment which perhaps did not involve music in the literal sense (though the Greeks would certainly have called it mousikē) was the recitation of the poems of Homer by ‘rhapsodes’ (see p. 10). One which certainly involved a great deal of music was the performance of dithyrambs.

In its very early stages the dithyramb was apparently just a merry song, sung by anybody who was feeling up in the world (usually after a few jars). In the sixth century BC it seems to have become organized into a song for performance by a choros of men or boys, accompanied by an aulos-player. At some time early in the fifth century professional aulos-players began to be employed, and they seem to have taken on themselves a more prominent role, putting in ‘intermezzi’ (anabolai) and indulging in elaborate displays of technique. There were calls for them to be put in their place; a poet called Pratinas is quoted3 as saying: ‘Let the aulos dance behind, for it is the servant (not the master).’

Dithyrambs were also performed at a number of other Greek festivals, including a number which were not dedicated to Dionysos,4 but the greatest celebration of this art form was without doubt the Great Dionysia. For certain administrative purposes, all Athenian citizens were assigned to one often ‘tribes’ or clans, and each tribe had to provide two choruses, one of up to fifty men and the other of the same number of boys. Each chorus performed a dithyramb, and there was fierce competition between them for the prizes. Compositions were specially commissioned for the occasion, and the tribes vied with each other to secure the services of the best composers, musicians and chorus-masters. We do not know precisely where they were performed, but it must have been in a wide open space with room for some hundreds of singers and a large audience. The choirs at this festival apparently stood in a circle, and did not dance as part of the performance, as the ‘choruses’ in the drama did.

From the musical point of view, the drama festival was much the most important part of the Great Dionysia. It involved tragedies, comedies and satyr-plays, which will be dealt with individually later on.

The great games of ancient Greece, which were in themselves religious festivals, involved a lot of musical activity. At the other games (the Olympics, the Isthmians, and the Nemeans) the contests were almost entirely athletic, but at the Pythian games at Delphi (held in honour of Apollo, the divine musician), there were contests for musicians who performed with the same competitive fervour as the athletes. There were a number of different ‘events’, in which the players could show their special skill. The most prestigious was ‘singing to the kithara’ (kitharōdia in Greek), an art form in which one man (women never competed) was poet, composer, singer and his own accompanist. The compositions they wrote and performed were called ‘kithara-singers’ nomoi’; this was the genre in which the most famous innovators made their mark, and to excel in it was their ultimate ambition. There were also contests in kithara-playing on its own, called by the Greeks psile kitharisis, a title meaning ‘mere’ or ‘bald’ kithara-playing, which may possibly convey a disparaging tone. Perhaps the occasional virtuoso player whose singing voice or poetic skill did not match his playing might compensate by a brilliant display of instrumental technique. The woodwind players were not left out either; they performed solos which were known as ‘aulos-players’ nomoi’ – extended instrumental pieces with a number of ‘movements’, some of which seem to have been in the nature of programme music. One famous example told, in five sections, the story of the victory of Apollo over the mythical monster called the Python at Delphi – a very suitable subject for the venue. There were also vocal compositions, intended to be sung to an aulos accompaniment, which of course would require two musicians. This type of duet performance was called aulōdia, and figured in the programme at Delphi from a very early date. One ancient writer tells us5 that some of the typical compositions for aulōdia had tragic or funereal associations, and for this reason were eliminated from the programme in about 578 BC, but this is not certain.

Music was by no means confined to the Pythian games, or to the strictly musical contests. There are plenty of vase-paintings from the mid-sixth century BC onwards which show athletes competing in almost every kind of event – running, long-jump, discus, javelin, and others – with an aulos-player standing nearby and obviously playing (Figure 1.4). It is tempting to wonder whether this helped or hindered the athletes.

It is also well known that ‘victory odes’ (epinikia in Greek) were composed in honour of those who won the most important prizes. One of the most successful poet/composers in this genre was Pindar, and a considerable amount of his work survives; unfortunately, we have only the words without the musical notation. He celebrated drivers of chariots (the most wealthy of the competitors, and so the most likely to commission him), boxers, wrestlers, ‘long-runners’ (who ran a distance of about 2 miles), pentathlon winners, and others. He even wrote an ode celebrating a victory by an aulos-player called Midas who came from Akragas (the modern Agrigento). Luckily, the text of this poem (Pythian 12) survives, and the remarks of some ancient commentators give us some useful evidence on the construction of that instrument. There are some hints in the text of Pindar’s odes on the mode of performance, as he writes of himself and his singers in a proud and self-conscious tone. He seems to have employed a chorus of young men who sang and danced, accompanied by a kithara (for which he deliberately uses the old-fashioned word phorminx) or an aulos, or both.6 Where he mentions percussion, he is not in fact referring to his own compositions; for example, in two contexts7 he mentions ‘clashing cymbals’ and ‘beating drums’; but he is describing the worship of Demeter or Rhea, not a victory celebration. Again, on one occasion he calls on someone who happens to bear the same name as the Roman hero, Aineias, to ‘urge his comrades on to sing of …’, though whether Aineias was a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- Preface

- 1 Music in Greek life, poetry and drama

- 2(a) The aulos

- 2(b) Kithara and lyre

- 2(c) Other instruments

- 3 Scales, intervals and tuning

- 4 Music, words and rhythm

- 5 Music and acoustical science

- 6 Music and myth

- 7 The years between – Alexandria and southern Italy

- 8 The Roman musical experience

- 9 Notation and pitch

- 10 Some surviving scores

- Appendix 1 Technical analysis of greek intervals

- Appendix 2 The construction of the water-organ (hydraulis)

- Appendix 3 The brauron aulos

- Notes and suggested reading

- Index