![]() Part I

Part I

Place Making![]()

Organizational Change 1

Philip Kuttner, Jack Tanis, Kevin Kampschroer, Judith Heerwagen and Francis Duffy

Editor's Introduction

Philip Kuttner

In Chapter 17, “Measurement: The Key to Reinventing the Office,” Francis Duffy describes how the fabric of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century office buildings were the architectural embodiment of Taylorist principles. Twenty-first-century business practices, impacted by the liberating and democratizing influence of Information Technology, are in a state of flux. How can the design professions, in dialog with the business community, develop a new architectural paradigm?

The authors of this chapter all have one thing in common: they have each committed their careers to advancing the knowledge required to transform the workplace into a powerful and competitive environment for organizations and their employees. My hope is that after reading this chapter, we will all be in a position to go forth into our own as well as our clients’ organizations and make an effective case for the argument that truly effective organizational change can only be achieved with parallel change in the design of the workplace. Jack Tanis is the Director of Applied Research at Steelcase Inc. and has been deeply involved in workplace research and design for many years. Jack leads the Steelcase research teams to develop and implement advanced office concepts. Kevin Kampschroer is the Director of Research and Expert Services for the United States General Services Administration’s public building service. As a result of his work with facility disciplines, leading companies and national universities, Kevin has been widely recognized for his leadership role in examining and measuring the important relationship between space and productivity. Judith Heerwagen leads her own research and consulting firm in Seattle, J.H. Heerwagen & Associates; she is widely respected for her unique perspective as an environmental psychologist and for her extensive research and writing which is focused on workplace ecology, the psychosocial value of space and the human factors of sustainable design. Finally, Francis Duffy is recognized internationally for his research and writing on the design and analysis of office space; he is probably best known for his pioneering work in helping corporations use space more effectively over time.

Workspace and Behavior

Jack Tanis

My perspective is a business perspective since my formal education was in Business and Economics. I would like to start with a question that our Chief Executive Officer, Jim Hackett, would typically ask CEOs in other businesses. His question gives us some idea of how business people talk to each other about “space.” I will start out with this provoking thought: “Why bother with space at all?” If I really start to dig deep into a CEO’s mindset, I would want to know if there is the desire not only to minimize space, but possibly to get by without space at all. In many cases space is viewed as a necessary evil and many business leaders do not understand space and its role in helping to facilitate their organizational change. To illustrate this point further, I refer to the concept of User Center Design as practiced by IDEO, one of Steelcase’s sister companies. Their studies start out with the observation of people; however, they go beyond observation and into the realm of analysis of the data gleaned through observation. We learn from cultural anthropologists that most people engage in observation to confirm concepts they already hold. The disciplined science of observation enables cultural anthropologists to discover patterns of behavior. They see users in the context of what they do; the key is to be able to improve profitability by creating a new experience. Therefore, we should ask ourselves exactly what that pleasurable experience is and how we can best support it. The solution therefore lies in observing, discovering and co-creating space with the same attention that we devote to the product development cycle. At Steelcase we have been attempting to utilize this User Center Research method to help create space. A relevant analogy would be with Amish barn raising; the delightful aspects of Amish barn raising are, first, that it all happens in one day and, second, that it is a combination of individual and community collaboration. The idea of community participation in the creation of the built environment is what I would like to focus on; the creation of space is one particular kind of experience and the use of space also creates a shared experience.

The history of the office as a workplace illustrates that there is a close correlation between the way people are governed and the layout of offices: rigid organizational structures that are manifested in conventional office layouts. However, this bears little relationship with the way more and more people are working nowadays. Business practices today are far more complex than they used to be and behavioral change is the key to innovation. Hierarchies are giving way to human networks and the networks are acting as catalysts to behavior. The key is to understand people’s behavior and to develop ways of changing behavior over time.

Hierarchies are bound by the shape of the corporation and the hierarchy is limited to what’s inside the four walls of an office. However, networks know no boundaries; they spread, they connect and they are based on trust. Peter Drucker said a few years ago: “Old organizations are based on force and new organizations are based on trust.” The emerging networks are expressions of trust between people. It would therefore make sense to look at workspace as an opportunity to provide proximity and relationships in the network; such spaces can be dedicated to individuals or groups.

If buildings can shape behavior, then how can we design buildings to assist in behavioral change? We found that our own User Center Research showed us a number of things that we were able to verify through observation. Historically, in a typical office configuration 70–80 percent of the space is dedicated to individuals. We will call this “I” space. Therefore the remaining 20–30 percent is “we” space. We started by looking at our own leadership community and we found that we needed a ratio of 30–40 percent of “I” space and 60–70 percent of “we” space. Not everyone goes that far but encouragingly we see many examples of a 50:50 split where the collaboration space is really the key to supporting the knowledge-based culture. The convergence of proportions demonstrates an enormous shift.

At this point I would like to examine the definitions of efficiency and effectiveness. In 1963, Peter Drucker defined efficiency and effectiveness as follows: “Efficiency is doing things right, effectiveness is doing the right things.”1 He also said: “Businesses are dominated by efficiency measures and need an equal imbalance of effectiveness measures.” Forty years later we still have the same need. We still do not have an equal imbalanced set of effectiveness measures. The following are some of the more common efficiency measures which will be familiar to anyone in the world of architecture and design: efficient use of space, square footage, churn, asset management, accommodation technology, procurement process, and satisfying environmental issues. The measures of effectiveness relate to helping people be more effective; they are about fostering innovation, enhancing communication, encouraging learning, improving work process, expediting decision-making, and so on. It should be obvious that management uses the former more frequently than the latter.

So how can we all facilitate the changes I describe? We should use the principle of applied research. The key is to learn experientially; we get the user involved in the experience of what really needs to happen. So we structure this using “ask first” questions just like those used in surveys. We use cultural anthropology techniques to get deeper into observation and interpretation; we then make a new experience by prototyping it and we follow this by asking and observing all over again. We offer this service in the form of three-day workshops where we go through an ask, observe and make sequence. We have carried out a number of these workshops at leading corporations; the outcome frequently inspires our clients to adopt a completely different way of thinking about themselves. The teams that engage in these workshops generally include architects, facilities managers and all levels of management, i.e. top management, middle management and users. The main objective is to go on observation safaris that allow them to gather information about their own organization. When this information is collated and analyzed, it is quite obvious that this process is very different from a traditional programming exercise.

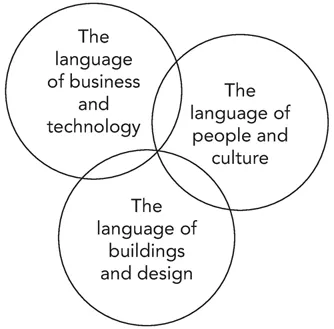

One of the most important parts of this process is to close the gap between the language used by the design and the business disciplines. Design professionals sometimes have a difficult time speaking the language of business and the business community is quite frightened of design language because they don’t understand it. Our hypothesis is that the language of people and culture is the best way to bridge this gap (Figure 1.1). In other words don’t leave your people (i.e. the users) at the kids’ table. If users become engaged, they will understand a new process; they will be more creative and most importantly they will buy in to something new. The idea is to get users to participate. Where necessary, the idea is to “irritate the

oyster” by disrupting commonly held assumptions in a clear and visible way so that people “get it,” i.e. they start to understand the reason why the change in the process is necessary.

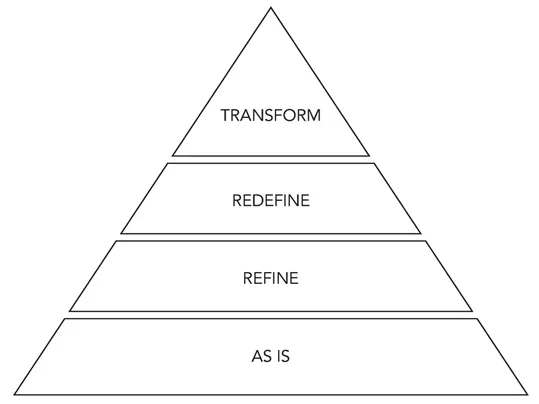

There are many different levels of change. We can illustrate this by using the concept of Joe Pine’s pyramid from the Experience Economy2 and we can put a little different spin on it (Figure 1.2). The lower level is “As Is”; it is about first costs, standards, status quo and also possibly about the introduction of new products. This is a new engagement or the recognition that something needs to change. The next level is “Refine”; it is about moderate changes in space, technology, work processes and culture. The third level offers to “Redefine” any one of the four categories in the previous level. The fourth level is “Transform” which is about fundamental breakthroughs and new discoveries.

Conclusion

One of the things that we like to say is that space does not necessarily lead to transformation but it needs to support transformation. Therefore, in any kind of cultural transformation we really need to focus on space in order to support change. Over the years we have advised a number of corporations and in each case we have helped them to build a prototype site at

either the “Redefine” or at the “Transform” level where they have changed their technology and their work processes. They did this by observing and engaging their own users, implementing a User Center Design pilot site and validating it before embarking on a large-scale implementation. All these clients believed that they had a fundamental need for organizational change in the way that they operated in order to survive and go forward. Our goal at Steelcase is to help people work more effectively and to help organizations work more efficiently, we believe it is important to consider both of these issues together and not separately.

Cultural Alignment

Kevin Kampschroer

The General Services Administration has a unique opportunity to influence the work environment because our mission is to “help federal agencies better serve the public by offering, at best value, superior workplaces, expert solutions, acquisition services and management policies.”3 The most significant aspect of that mission statement is that it says “at best value” not the cheapest way possible. We are responsible for 31 million square meters of space around the country, 8,300 facilities and 1.1 million tenants. We operate on a business footing: we collect rent from our tenants, we generate $8 billion in revenue and we produce about $800 million in net income which we give back to our board of directors.

Ironically both the federal government and the space it uses have grown pretty dramatically over the past 35–40 years; almost all of this increase has been in leased property due to the changes in the way space is being used over time in the federal government (Figure 1.3). One must also remember that for most organizations during this period the nature of work itself has been changing; outsourcing in both the private and public sector is probably the principal cause of this change. Another critical generator of change has been the gradual recognition of what the core values and the core competencies of a company might be. We are not doing the same kind of repetitive work any more; we’re not facing the same kind of problems day after day. Work is becoming more strategic; the new approach creates greater value for organizations. As the nature of each task has become more individual, much more collaboration occurs; work is much more improvisational. It is these new circumstances that we need to tackle in the design of the workplace.

So where do we start? What do organizations care about? They only care about cultural alignment. All the research that’s been done in the behavioral and business worlds over the past 40 years has shown that cultural alignment, i.e. the quality of work-life, allies itself with high performance; if you don’t have cultural alignment, your organization doesn’t perform well. Our research has shown that there is the potential for space, buildings, or the physical environment to affect and improve organizational change. The basic thesis of all the contributors in this chapter is that for organizations to change dramatically, they have to have a corresponding component of architectural change. Now, I pr...