![]()

1

‘NOTHING SO PRACTICAL AS GOOD THEORY’

Legitimation Code Theory in higher education

Christine Winberg, Sioux McKenna and Kirstin Wilmot

Introduction to higher education studies

The earliest universities served the dual aims of knowledge production and social reproduction. They ensured that an elite group were inducted into their roles at the apex of society’s stratification and they were spaces for knowledge to be advanced and disseminated within this group. The aims of higher education institutions have become far more complex over a number of centuries, and the pace of complexity has accelerated exponentially since the last decades of the twentieth century with no signs of slowing. The early aims of social reproduction and knowledge production have been dramatically reframed in this era of supercomplexity. Widening participation in higher education has shaken the social reproduction aim and the emergence of the knowledge economy has shifted the ways in which knowledge is produced and disseminated.

As universities have broadened access beyond the elite, so the approach to teaching and to what gets taught has changed. The purpose of higher education has increasingly come to be the preparation of young people across society to take on highly skilled positions in industry. As Trow (1973) points out, massification is about much more than having to accommodate greater numbers in the system, it is about changing the basic nature of the institution. Many of the assumptions underpinning the more homogenous predecessors to the modern university have proven problematic when the student body brings with it a varied spectrum of languages, literacy practices, cultures, beliefs, values, prior education experiences, and so on. The inability of universities to adjust to such variation is most evident in the strong correlation between social class and student success across the world (Mettler, 2014; Case, Marshall, McKenna and Mogashana, 2018). Despite claims of being a meritocracy whereby it is on the basis of individual intelligence, skills and work ethic that students fail or succeed, universities often continue to play their earlier role of social reproduction. This has become a central concern for those who see the modern university as a space for social justice.

The notion that knowledge drives the economy has meant that a university education is highly desirable as a means of both individual social mobility and national economic growth. Technological advances and breakthroughs in multiple fields have led to rapid changes in curricula. Alongside these changes in content have come changes in understandings as to the role of the university, with demands that our institutions become more efficient and be more closely managed towards this end. This has led to the emergence of the administrative university where the collation of metrics occupies a great deal of time alongside the other practices expected of institutions.

Within this context, it is unsurprising that there has been an enormous growth in the field of higher education studies. Academics and postgraduate students have developed research projects and published thousands of articles looking at who gets access to higher education and who gets to succeed within it (Harland, 2009; Tight, 2014). Much of this research has a strong ideological intention and often focuses on classroom practice and assessment; however, it often lacks strong theory (Clegg, 2009a, 2009b; Shay, 2012) which makes it susceptible to common-sense conclusions underpinned by unexplored assumptions (Hlengwa, McKenna and Njovane, 2018; Boughey and McKenna, 2016). Furthermore, it has been noted that the concern with how higher education often serves to reproduce social inequalities rather than dismantle them has led to a curious blind spot in much of the research – that of knowledge itself. In looking at how curricula are structured and what happens in our lecture theatres, many studies have failed to consider how it is that certain knowledges are legitimated and others are not, and how it is that each discipline structures its knowledge and determines the kind of knowers who are deemed worthy of disciplinary membership.

This book brings together a rich collection of studies that uses a common framework, Legitimation Code Theory, to attend to these concerns about higher education studies. The framework acts as conceptual lenses, analytical tools and as teaching resources to open conversations about how it is we come to know and what it is that is deemed worth knowing.

An introduction to Legitimation Code Theory

Legitimation Code Theory or ‘LCT’ is a sociological framework motivated by issues of social justice and knowledge-building. It was developed from the late 1990s by Karl Maton and builds primarily on the sociological frameworks of Pierre Bourdieu and Basil Bernstein, as well as critical realist and critical rationalist philosophies (see Maton, 2014, 2018). The framework is multi-dimensional, offering a variety of concepts and tools to analyse practices. Three of these dimensions – Specialization, Semantics and Autonomy – are pertinent to this book. Each dimension explores a set of organizing principles of dispositions, practices and fields, conceptualized in LCT as different species of legitimation codes. An analysis of legitimation codes explores ‘what is possible for whom, when, where and how, and who is able to define these possibilities, when, where and how’ (Maton, 2014, p. 18). LCT is increasingly being used as a primary framework to analyse the legitimation codes that enable or constrain knowledge-building in education contexts. In this sense it is able to reveal the ‘rules of the game’ by making the basis of success of any practice explicit. This has major implications for social justice in higher education, as these ‘rules’ can then be taught and learned more explicitly and they can be challenged and changed. This section provides a brief introduction to the LCT concepts used in this volume. For a fuller explanation of the framework and concepts, see Maton (2014, 2016a, 2016b, 2020) and Maton and Howard (2018).

Specialization

Specialization explores the basis of achievement underlying practices, dispositions and contexts (Maton, 2016a, p. 13). It begins from the simple premise that all practices are about or oriented towards something and by someone. One can, therefore, analytically distinguish: epistemic relations between practices and their object (that part of the world towards which they are oriented); and social relations between practices and their subject (who or what is enacting the practices). For knowledge claims, these are realized as: epistemic relations between knowledge and its proclaimed objects of study; and social relations between knowledge and its authors, actors or subjects. These relations highlight questions of: what can be legitimately described as knowledge (epistemic relations); and who can claim to be a legitimate knower (social relations).

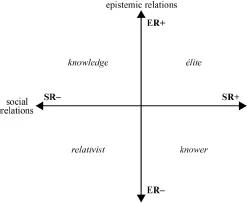

Practices will always have both epistemic relations and social relations – there are always knowledge and knowers. Each of these relations may be more strongly (+) or weakly (−) emphasized and the two strengths together generate specialization codes (ER+/−, SR+/−). As shown in Figure 1.1, these strengths are visualized on the specialization plane, a topological space of infinite positions but with four principal modalities:

FIGURE 1.1 The specialization plane

Source: Maton, 2014, p. 30

• knowledge codes (ER+, SR−), where possession of specialized knowledges, principles or procedures concerning specific objects of study is emphasized as the basis of achievement, and the attributes of actors are downplayed;

• knower codes (ER–, SR+), where specialized knowledge and objects are downplayed and the attributes of actors are emphasized as measures of achievement, whether viewed as born (e.g. ‘natural talent’), cultivated (e.g. ‘taste’) or social (e.g. feminist standpoint theory);

• élite codes (ER+, SR+), where legitimacy is based on both possessing specialist knowledge and being the right kind of knower; and

• relativist codes (ER–, SR−), where legitimacy is determined by neither specialist knowledge nor knower attributes – ‘anything goes’.

In brief, knowledge codes emphasize what you know, knower codes emphasize the kind of knower you are, élite codes emphasize both what you know and who you are, and relativist codes emphasize neither (Maton, 2016a, p. 13). One specific kind of code can come to dominate as the basis of achievement or codes can shift over time. Analysing specialization codes is useful because they are not always transparent and universal and they are often contested. They also frequently result in ‘code matches’ and ‘code clashes’ in practices. A ‘code match’ is when two sets of practices or actors share the same basis of success and thus work harmoniously together towards shared goals. A ‘code clash’ occurs when conflicting codes work against each other (Maton 2016a, p. 13). Chapter 13 (this volume), for example, uses specialization codes to look at programme renewals in a South African university context. The authors show how programme renewal is conceptualized by academic staff in terms of both epistemic relations which distinguish between different specialized knowledges (e.g. disciplinary content, curriculum design etc.) underpinning the practice of programme renewal in universities, and in terms of social relations between the different dispositions of actors (e.g. personal experience, attitude) involved in the renewal process. This enables the authors to analyse competing claims to legitimacy in this context.

Semantics

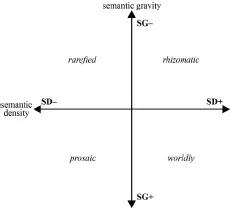

Semantics explores the context-dependence and complexity of practices (Maton, 2016a, 2020). The central code concepts in Semantics are semantic gravity and semantic density. Semantic gravity (SG) refers to the degree to which meaning relates to a context: the stronger the semantic gravity, the more context-dependent meanings and practices; the weaker the semantic gravity, the more context-independent the meanings and practices. Semantic density (SD) relates to complexity of meanings. The stronger the semantic density, the more complex the meanings – typically as a result of condensing many meanings into instances of practice. The weaker the semantic density, the less complex meanings. When varying strengths of semantic gravity and semantic density are combined on a semantic plane, four principal semantic codes are generated. These are illustrated in Figure 1.2.

FIGURE 1.2 The semantic plane

Source: Maton, 2014, p. 131

Maton (2016a, p. 16) summarizes these principal modalities as follows:

• rhizomatic codes (SG−, SD+), where the basis of achievement comprises relatively context-independent and complex stances;

• prosaic codes (SG+, SD−), where legitimacy accrues to relatively context-dependent and simpler stances;

• rarefied codes (SG−, SD−), where legitimacy is based on relatively context-independent stances that condense fewer meanings; and

• worldly codes (SG+, SD+), where legitimacy is accorded to relatively context-dependent stances that condense manifold meanings.

Semantic codes complement specialization codes in that they illuminate a further set of organizing principles of practices. Once these codes have been revealed through analysis, changes in knowledge practices can be mapped using semantic profiles (see Figure 1.3). Profiling is a useful analytical tool because it is able to show shifts in practices over time.

Mapping semantic codes over time allows for different profiles to be revealed. Educational research (see Maton 2020) has shown that flat-lines (either high flat-lines such as profile A, or low flat-lines such as profile B) limit the potential for knowledge-building as the knowledge enacted is confined to a relatively small range of semantic gravity and semantic density. In contrast, the formation of semantic waves, as illustrated in profile C, has been shown to be one tool for cumulative knowledge-building in classrooms in that it enables a greater semantic range for students and teachers to draw on (e.g. Clarence, 2016; Wolff and Luckett, 2013). The specific shape of a wave is not important here; rather, the ability to traverse the f...