- 454 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About This Book

Le Théâtre du Soleil traces the company's history from a group of young, barely trained actors, directors, and designers struggling to match their political commitment to a creative strategy, to their grappling with the concerns of migration, separation and exile in the early decades of the twenty-first century.

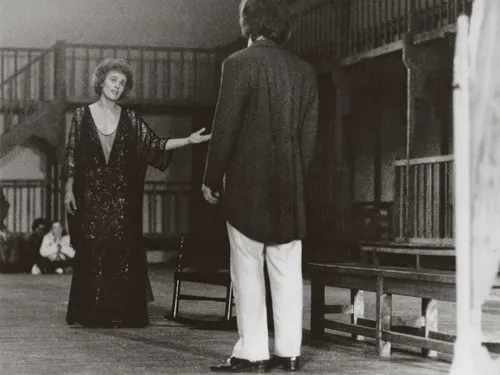

Béatrice Picon-Vallin recounts how, in the 55 years since its founding, the Théâtre du Soleil has established itself as one of the foremost names in modern theatre. Ariane Mnouchkine and her collaborators have developed a unique and ever-evolving style that combines a piercing richness of shape, color, and texture with precision choreography, innovative musical accompaniment, and multi-layered, metaphorical dreamscapes. This rich, storied history is illustrated by a wealth of spectacular rehearsal and production photos from the company's own archive and interviews with dozens of past and present members, including Mnouchkine herself.

Judith G. Miller's timely translation of the first comprehensive history and analysis of a remarkable, award-winning company is a compelling read for both students and teachers of Drama and Theatre Studies.

Frequently asked questions

Information

1 Destiny

“A popular theatre piece is theatre that’s beautiful and easy to read; it speaks to something important, something that’s really meaningful to ordinary people.”Ariane Mnouchkine1

“We were making art; we were making art for the people; we were happy.”Off-stage voice of the Narrator from The Survivors of Mad Hope

“We invent theatre, that mysterious continent that theater always is for me, needing always to be redefined; we discover all the time archipelagos and shores on which others have, of course, already landed.”Ariane Mnouchkine2

Artisan-Companions

A genealogy: finding their place slowly in theatre history

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- A word from the author

- A word from the translator

- Opening: For all those who have worked, or are working, with the Théâtre du Soleil

- Prologue: origins

- Chapter 1 Destiny

- Chapter 2 Collective creation (second try, first draft)

- Chapter 3 The Shakespeare Cycle

- Chapter 4 A new way of writing: creating the great Asian epics

- Chapter 5 The House of Atreus Cycle or the archaeology of passions

- Chapter 6 The Soleil brings in a camera

- Chapter 7 Ten years of collective creation: between cinema-theatre, documentary theatre, and the lyrical epic

- Transverse perspectives: six thematic illustrations

- First Epilogue (2014): the galaxy of the Soleil

- Second Epilogue (2019): returning to Asian sources, expanding, and transmitting

- Appendices: chronology and awards, theatre programs and posters