eBook - ePub

Masterplanning for Change

Designing the Resilient City

This is a test

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Masterplanning for Change

Designing the Resilient City

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Cities are under increased pressure to be resilient and resistant to the effects of climate change and rapid urbanisation. However, this idea has still not been fully integrated in to practice. This book presents a practical approach to masterplanning the city and its areas (existing and new) as urban environments for the 21st century, addressing the design of cities as complex adaptive systems.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Masterplanning for Change by Ombretta Romice, Sergio Porta, Alessandra Feliciotti in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

TOWARDS AN ECOLOGY OF URBAN FORM

1 Design and change: reconciling the paradox

2 From system ecology to urban morphology paradox

CHAPTER 1

Design and change: reconciling the paradox

Let’s start with one fundamental truth: cities change. Their economy changes, the socio-cultural landscape in which they exist changes and we are immersed in this permanent flow of multifaceted interdependent change, individually and collectively, to which we contribute and by which we are shaped.

The form of cities changes as well: buildings, plots, street fronts, blocks, streets and districts, each at their own pace. Certain elements do so rather frequently, such as the internal arrangement of furniture in a building; others more slowly and rarely, such as the layout of a street.

Crucially, each of these transformations exerts an influence on what is around: for example, a well-visited museum may instigate guest houses to settle in its vicinity, occupying rows of previously residential townhouses by merging adjacent plots of land and opening doors across the party walls. At the same time, the other processes that co-exist with form in cities – economic, social or cultural – also change in their own way and at their own pace, and they influence each other. In doing so, they produce a tangible impact on our material urban environment. An environmental psychologist would say that these are ‘transactional environments’:1 they affect and are affected, so they are never static. This leads to a second fundamental truth: cities are complex. They are, in fact, more complex than any other artefact of human culture by far.

Confronted by these two unquestionable truths, how can we suggest that it is possible to design, to masterplan moreover, something that is so complex and that, by its very nature, constantly changes?

We are in front of a paradox which can be overcome if we make two shifts.

- The first shift is conceptual and entails putting the notions of time and change at the core of any credible design approach. In fact, all that can be designed in a city, all that is physical in it, changes in time. Urban form is not an unalterable substrate over which biologic, social, economic or cultural dynamics occur. Rather, itself with all its components, from smallest to largest, from plots to street networks, neighbourhoods and districts, is a complex adaptive system. That entails extending a view on complexity to the physical form of cities. Rather than the substrate, it here becomes a subject matter of change, along with the non-physical systems with which it constitutes a larger, interdependent whole. Consequently, we conceive the good city as a mobile target, in fact a trajectory of change, which the masterplan distinctively contributes to the shaping of the route. This evolutionist approach allows us to observe and design the physical city in relation to key properties and processes that are typically associated with complex adaptive systems in general: resilience, first of all.

- The second shift is more practical. It entails understanding what should be designed and what needs not be designed, which is left to the emergent and largely self-organised effects of life in time. In this sense, designers should make the rather counterintuitive effort of deciding ‘what not to design’ a lot sooner and with as much critical thinking as deciding ‘what to design’. In most cases, this means designing less but, also, designing what counts more.

The consideration of urban form as one constituent layer of the complex city in evolution is not entirely new to certain specialist disciplines, as we shall see, but it is still quite a leap for designers. The next chapter introduces how it originally came to be in the context of the ‘science of change’ in nature, society and culture. Before we start, we need a quick look at where we are in our understanding of cities, with the challenges that the ‘urbanisation age’ and the ‘Great Acceleration’ are placing before us, and what is at stake if we fail to equip ourselves with the best knowledge, practices and tools to address them.

1.1 Urbanisation, Anthropocene and the Great Acceleration

In mid-2009 the United Nations formally announced that cities had reached a global milestone. For the first time in history, urban dwellers outnumbered the rural population, effectively ushering us into the so-called ‘Metropolitan Century’.2 Recent projections by the United Nations set the current proportion of urban dwellers at 55% of the world population – about 4.2 billion people. If a century ago a mere 20% of the two billion people on this planet lived in cities, it is projected that by 2050 this proportion will rise to about 68% of the 9.7 billion total.3 Most urbanites will live in newly developed urban areas, as only about 40% of the urban areas that will exist in 2030 are already in place.4

Estimating the urban population is a very difficult task, and one very much dependent on how ‘urban’ is defined in the first place, which can be open to political and ideological biases.5 However, despite this definition issue, the trend is undeniable: more and more people worldwide, and for the most diverse reasons, choose to live in cities, which consequently grow at an unprecedented speed.

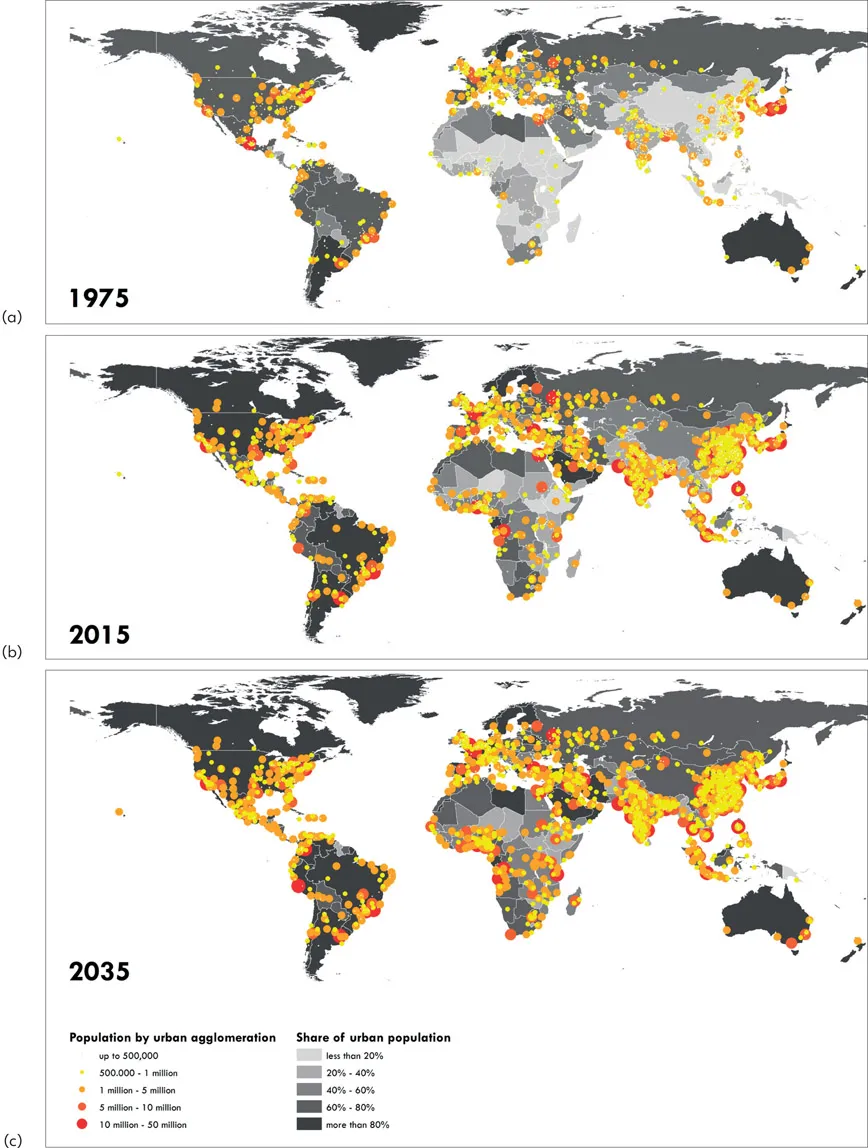

To complicate things, this heightened urbanisation is an uneven process, different in the Global South and Global North6 (see Figure 1.1). Cities in the Global South are experiencing, in the span of a generation, the growth that American and European cities experienced over more than a century ago. This growth is primarily driven by African and Asian cities which, according to the United Nations, will contribute alone to around 90% of the projected urban growth.7

Figure 1.1 Proportion of urban population by state and population by urban agglomeration: (a) 1975, (b) 2015 and (c) 2035

Unlike nineteenth- and twentieth-century urbanisation in the Western hemisphere, this new wave of development is occurring often in a climate of unstable state institutions, flawed legislative systems, political struggle and young planning systems.8 As a manifestation of these difficult conditions, a significant part of the new settlements will be only partially formal, in relation to land security, access to infrastructure and planning/building regulations. Already in 2014, nearly one-third of the urban population in developing countries – over 880 million people – lived in informal settlements that failed to meet basic requirements for tolerable living.9 The fear is that lacking effective strategies to fulfil and manage the rising demand for housing, food, water, transportation and basic infrastructure, this figure will keep soaring. At the same time, and to some extent even more worryingly, the formal part of the new settlements for the rising middle class of the Global South are mirroring the same unsustainable patterns of development that informed urbanisation in the Global North after the Second World War. This is evident in the emergence of fragmented, isolated, mono-functional estates, as well as exclusive gated communities, reinforcing circular dynamics of social segregation, inequality and car-dependency.10

In turn, most Global North cities are facing slow growth or even shrinkage, and over the next thirty years their future demand for housing, employment, transport, leisure and healthcare will be driven by the needs of a rapidly ageing population and fast technological, functional and locational obsolescence of the existing housing stock and infrastructure. Here it is also expected that in the same timeframe much of the existing built infrastructure will require extensive upkeep, upgrade or even comprehensive redevelopment.11 The challenge is not so much about building new cities but rather retrofitting, re-purposing and re-imagining what is already there.

The cumulative effect of urbanisation reverberates across various aspects of society, culture, economy and the environment. For the first time in history the impact of human activity has reached a point where it tangibly affects the fundamental patterns of nature, bringing us into a new geologic epoch named ‘Anthropocene’.12 While the origins of the Anthropocene have to be drawn back to the industrial age, it was only after the Second World War that its global impact started skyrocketing, building up the ‘Great Acceleration’.13 One of the direct consequences of that is most commonly referred to as climate change, the sharp increase of both the frequency and severity of natural disasters which threaten the livelihood, health and safety of billions of urbanites worldwide. The fear is that at the current impact rate humans will soon outpace the societal capacity to reverse the unsustainable trajectory we all are part of, resulting in threatening scenarios in the short to medium term.14

Urbanisation is, at the same time, effect and cause of the Great Acceleration. On the one hand, urbanisation is a consequence of natural population increase and migration, leading to building development and reclassification of land coverage. On the other, cities are among the principal drivers of human-induced change: they are responsible for 60–80% of world energy consumption and over 70% of global carbon dioxide emissions.15 Urbanisation has an important role in processes of ecosystem depletion and fragmentation, and contributes to creating disaster-vulnerable environments which exacerbate the negative effects of extreme weather events such as flooding, landslides, heat waves and droughts. Yet, cities are also considered part of the solution, exactly because – with their concentration of people and activities – they are incubators of the societal and technological innovations that are needed to reverse these current unsustainable trajectories of development. This will also require optimising the use of available resources, becoming more inclusive, connected, integrated and, crucially, more resilient socially, economically and spatially.

The challenge that our world is facing is increasingly urban and has inherently to do with how cities are changing and how they will change in the future. To address this, now and in the coming decades, urban designers must primarily develop a more profound understanding of what urban change really is. In order to do so, we need to focus first on the kind of change that occurs in complex systems, particularly as studied in the discipline of ecology.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- CONTENTS

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword: plan less to plan better

- Preface: towards masterplanning for change

- PART I TOWARDS AN ECOLOGY OF URBAN FORM

- PART 2 MASTERPLANNING FOR CHANGE: THE DESIGN APPROACH

- References

- Image credits

- Index