Long before they come to school or are involved in reading and writing instruction, children from a wide range of cultural, socio economic and language communities are able to talk about and participate in the literacy events that exist in their world. The chapters in Part I, What Children Know about Literacy, show how children actively and personally contribute to their coming to know literacy—the continuous expansion and reorganization of concepts that children construct as they engage and transact with literacy practices and the users of literacy in their lives. Learning is always both personal and social. As a result of the literacy opportunities in their homes and communities and with the people in these various environments, children apply their unique understandings as they differentiate drawing from conventional systems of writing and other symbol systems. They come to know how written language serves their own specific literacy functions. They use play acting, illustration, numeracy and talk to support their literacy development and to develop their own understandings about the characteristic differences in these systems and how each relates to reading and writing.

To develop insights into what children know about language, the authors in this part carefully analyze children’s engagements with the artifacts in their environment: their writing and reading, their use of numbers, their responses to musical notation, to illustrations and to the wide ranges of types of print in different environments. As a result, they interpret and provide evidence of young children’s expanding knowledge about literacy and its relation to the communities in which they live. Such microanalysis of children’s literacy practices reveal how children actively and continuously develop their literacy concepts in transaction with the uses of literacy and the users of literacy in their lives. They show that literacy development is a profoundly constructive and inventive process.

Children from rich and poor communities, growing up with different ethnic, linguistic, and racial backgrounds from different countries show similarities in the ways in which they respond to and learn from literacy opportunities and experiences. At the same time, their literacy development is influenced by the attitudes that society has about how literacy is learned, who is considered literate and what is considered to be literacy.

Chapter 1

Effective Young Beginning Readers

Debra Goodman, Alan Flurkey, and Yetta Goodman

In an interview with the school librarian, 5-year-old Lauren1 is asked if she is a good reader. Lauren says, “I don’t know how to read. But I know how to read my Barney book.”

When asked, “How can you read that [Barney book]?” Lauren replies, “I like to read.” She goes on to say, “And sometime I be making up stories. And books.”

“You mean like look at a book and make up a story? Is that how you do it?”

Lauren agrees, “If I don’t know how to read then I’ll do that.” She adds, “Sometimes I look at the pictures to figure out. I practice and I use the alfulbet to learn it.”

“How does the alphabet help you to read?”

Lauren explains, “Like if…like…I take a book and I open this book and I make the story up and I read it. And sometimes I don’t know how to read, or it’s bedtime—my mommy reads a story to me and then we’ll watch TV and then go to bed.”

Lauren says she doesn’t know how to read. Yet her comments reveal that she has had a lot of experiences with texts, and has already developed strategies for making sense of books. Her talk reflects how reading is a part of the everyday family routines that shape her life.

Our studies of young children’s reading have shown that the majority of kids in every classroom are reading connected texts in books related to their own background knowledge and language within a year or two after kindergarten. And a growing number of children are coming to school already reading. Many of these students are eager and enthusiastic about reading. They have been read to for years. They have been encouraged to read along with their teachers and parents. They sit for a long time examining the illustrations and exploring the printed text, sometimes reading aloud to friends, dolls, or imaginary audiences.

At this point in their development, most young readers are using all the language cueing systems and available resources with their major focus on making sense of the text, making effective use of reading strategies. We use the phrase effective young beginning readers to describe children from the age of 4 to 8 who are intelligently sorting out how reading works, but who are still inexperienced in selecting and integrating the language cueing systems (graphophonic, syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic) and their reading strategies (i.e., sampling, selecting, predicting, inferring, and confirming).

Parents and caretakers enjoy watching their preschooler’s playful responses to books and development of early reading strategies. But once children reach school age, parents and teachers worry when young children’s reading does not conform to adult conventions. They become concerned when young readers make up parts or reread portions of a written text, use clues in the illustrations to complete the story, or substitute words that look different from the text. The response of concerned adults is to ask readers to pay attention to the accurate reproduction of the text. Instead, we encourage parents and teachers to kidwatch (Owocki & Goodman, 2002) and appreciate the reading development taking place before their eyes.

Effective young beginning readers already know a lot about reading. Like Lauren, they are aware of the function print serves in their daily lives. They read and write their names and the names of people they love. They know that the letters in their names relate to the sounds of oral language. They know that the language of birthday cards is different from the language of their favorite stories. They know stories and books are organized differently from grocery lists. They know how to open books and are aware of the directionality of the print.

Like all learners exploring new areas, young readers are tentative as they become more independent in their response to print in books. They are using language cueing systems and reading strategies but not always with the confidence that comes with greater experience. They are not always sure about what features of text to pay most attention to. They are influenced by their own problem-solving strategies to construct meaning with the printed text as they become aware of the relationship between the written and oral language systems. At the same time, they are influenced by social interactions and instructional practices of parents and teachers.

Young readers are coming to know reading in the same way that all of us are always developing our reading abilities—through working with new and unfamiliar texts. But in their short literacy histories, they are still exploring the complexity of making meaning with written texts. In the United States these readers are most commonly in first grade. But we have worked with effective young readers in preschools and kindergartens, and some second and third graders are still working through the process of becoming effective readers. Our observations that reading involves working hard2 with a text helps us to view struggling readers in a different light. We consider struggling to make sense an important and integral part of reading development. This language-learning-as-problem-solving (Taylor, 1993) continues and expands throughout readers’ lives.

In this chapter, we describe the strategies and qualities of effective beginning readers based on research observations and miscue analysis (Y. Goodman, Watson, & Burke, 2005). We document children learning to read through experiences with texts and the process of working at making sense. We discuss influences of instruction at home and in school and make suggestions for supporting meaning making in beginning readers. We begin with Mike.

MIKE READS WE PLAY ON A RAINY DAY

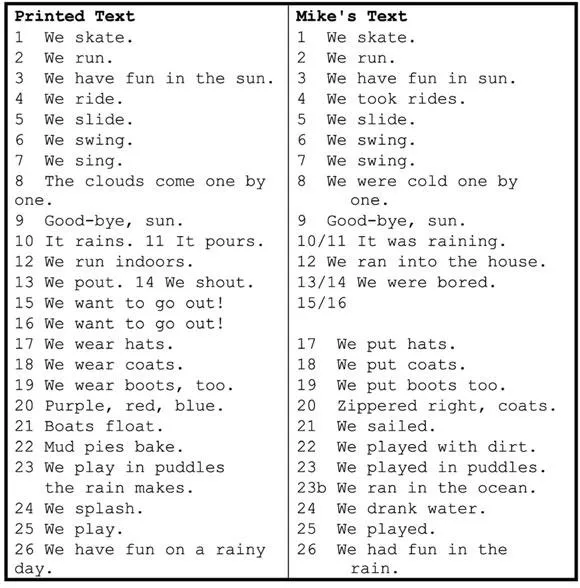

Mike was in the second half of first grade when his parents brought him to the Reading/Writing Learning Clinic at Hofstra University because of concerns about his reading. Mike was asked to read the book We Play on a Rainy Day (Medearis, 1995) as part of an evaluation. In order to demonstrate making sense as a “text construction process,” Figure 1.1 compares the printed story text to Mike’s oral reading (Mike’s Text). We’ve numbered the sentences for reference sake.

When compared to the printed text, Mike’s oral reading appears substantially different. For example, in sentences 17–19, he substitutes put for wear and in sentence (S) 22 he substitutes played for pies. He omits words (S3. We have fun in sun./ We have fun in the sun.), and even entire sentences (S14, S15, S16). He inserts words (S4. We took rides./ We ride) He even inserts a sentence (S23b. We ran in the ocean.). He also constructs sentences that are quite different in wording from the author’s text (i.e., S22. We played in dirt. for Mud pies bake.).

However, if we read Mike’s response as a separate text—a “reader’s text” constructed during the reading process (K. Goodman, 1996)—Mike has constructed a comprehensible story that parallels the author’s text in over-all meaning and tone. Mike’s text varies from the printed text in wording and phrasing, but both texts are about children playing in the sun, running inside when it starts to rain, and making the best of a rainy day. In this regard, Mike’s reading is emblematic of other effective beginning readers that we have studied.

Mike’s retelling also reflects his understanding of what he has read:

“They had fun in the sun, but it rained and they had nothing to do so they put on their coats, jackets, hats and their boots. And they zippered their coats up so they wouldn’t get cold. They were playing in puddles and drinking the rain.”

We define an effective reader as a reader who is successful at constructing meaning with a text. Mike’s reading is effective because he consistently focuses on making sense as he reads, is able to construct a meaning...