- 440 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Computer-Organized Cost Engineering

About this book

Providing a sequence of steps for matching cost engineering needs with helpful computer tools, this reference addresses the issues of project complexity and uncertainty; cost estimation, scheduling, and cost control; cost and result uncertainty; engineering and general purpose software; utilities th

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE

A Computer Technology View of Cost Engineering

Cost engineers are civil engineers, mechanical engineers, aeronautical engineers, and nuclear, chemical, and electrical engineers who take engineering a step further-into a cost estimate, into a scheduled plan, into a world of limited resources.

In the process, they may write a lot of numbers and sum them up. To the uninitiated, the cost engineer looks like a clerk, or like an accountant. At times he looks like an economist. The term “engineering” seems out of place. How wrong! It is subject-matter expertise that governs the profession. That is why a new high-rise cannot be estimated by a clerk, an industrial plant cannot be cost-assessed by an economist, and a nuclear reactor cannot be dollar-evaluated by accountants. The people in these discliplines have their hands full, and their contribution should not be underemphasized, but they are not cost engineers.

Computers gave the cost engineer a tool that added a new dimension to the profession. The use of computers in itself is an engineering endeavor, and so today the term “(cost) engineering” has a dual meaning: expertise not only in the subject matter but also in using computers in the process of optimizing resource allocation. The modern cost engineer is a central player in a competitive economy. His or her responsibility is to find ways to extract more results from finite dollars and limited time. And, conversely, he or she tries to engineer a solution to the problem of achieving a target result with a smaller investment.

Available resources are finite; expressive imagination is infinite. This anomaly is the challenge of cost engineering.

1

Elements

Cost engineering is a two-way window. Looking through this window the business community relates to science and technology. Looking the other way, scientists and engineers hear and see what business wants and does.

Cost engineering answers questions: How much does it cost? How long will it take? And later, Does it really cost and take as much and as long as predicted? The cost engineering components that handle these questions are cost estimation, scheduling, and cost control, the elements of cost engineering.1

The difficulty or simplicity of handling these questions depends on (1) the complexity of the subject matter, (2) the prevailing constraints, (3) the extent to which 1 and 2 are given or known.

(1) A formal definition of cost engineering is given by Humphreys 1984, 1987. Speaking officially as the executive director of the American Association of Cost Engineers Humphreys defines a cost engineer as “an engineer whose judgment and experience is utilized in the application of scientific principles and techniques to problems of cost estimation; cost control; business planning and management science; profitability analysis; and project management, planning and scheduling.” It is interesting to contrast this with an older definition given by Bauman 1964: “Cost Engineer A relatively new designation for any graduate or professional engineer or equivalent employing his technical skills in the practice of process cost estimation, cost control, profitability, or the general engineering economics of capital investment.” In most environments today, MBA’s and economists who are not engineers take hold of the overall business planning, and management, pushing the cost engineer into his core elements of cost estimation, scheduling and cost control.

When 1 and/or 2 comprise a great deal of data computers are called for. When they involve complex computations computers are relied on again. When the data and computation are generally unknown or ill defined computers will help simulate the missing link.

Business does not let go. The answers to the three basic questions are not enough, Can it cost less? Finish faster? Is it possible to anticipate disagreements about estimates versus actual costs earlier? Cost engineers are put on the spot. General engineering is not shy, either. Can we do more with the given budget, use the project time better, and allow earlier indication for surprises?

Both business and engineering tap the cost engineer’s shoulder: with: If I change my mind later, can it be done without a cost or schedule penalty?

These questions, driven by a competitive economy, place a great challenge at the door of cost engineering.

To meet this challenge, cost engineers had to grow from engineers who do clerical cost to engineers who do cost as mathematical abstraction. Computers took over the endless summations, the massive data handling, even the data entry and data display, and cost engineers moved on to wrestle with the complexity of optimal resource allocation.1

(1) One can hardly dispute the importance of resource allocation in any project, and economic activity, yet, it is quite an abstraction, and as a result cost engineering in general remains in relative obscurity. Webster New World Dictionary 1980 has an entry for civil engineering, but not for cost engineering. Even in the engineering community many confuse cost engineering with cost estimating or cost accounting. Major Engineering handbooks don’t mention cost engineering, not even as an index entry. Among them Kutz 1986 Mechanical Engineering Handbook, Kong 1983 Handbook of Structural Concrete, Grimm 1990 Handbook of HVAC, and Merritt 1983 Standard Handbook for Civil Engineers”. On the other end, non-engineering estimators and appraisers further blur the distinction of the cost engineering profession. It sounds impressive when an architect, or an engineer says: I designed this... or I built this... What can a cost engineer say? I costed this... I resource-allocated this... The situation is similar to that of an anesthesiologist who can not claim that he performed the surgery, but it is a fact that his expertise or lack of it will determine the recovery of the patient.

A resource is anything one can run out of, primarily time and money. Equipment, materials, skills — even job opportunities are all resources. The modern cost engineer builds associations of resources: dollars-time slots-crew-equipment-material-supervision.

Given n resources of one type and k resources of a second type, there are n * k possible “pairs” (allocations). Add m resources of a third type, and the number of three parts allocations becomes n * k * m. It grows fast. If there are 10 resource types and there are 100 items of each, then the possible allocations become

Given 10 day-long jobs, 10 crews, and 10 calendar days (all are resources), there are 10*10*10= 1000 theoretical allocations. Some of them, taken together, are impossible; others are possible but make no engineering sense; and some that make engineering sense don’t make business sense. Some combinations taken together will constitute a good overall plan. One of them will be best. Which?1

At first glance it may seem that computers, with their legendary speed, will be able simply to go through all the possibilities and offer a selection. A more careful review will show that even if computers become thousands of times faster than they are today, they will still be far too slow to crack the full-size allocation challenge.2 Therefore, it is necessary to use faith, experience, intuition, and heuristic — that which is not objective and mathematical — and through these strive for the best allocation. Computer-Organized cost engineering is not yet reduced to a recipe, expressed in formulas or software. There are recipes and there is a lot of software, but common sense and judgment are still very much in the game.

(1) See Conway et al 1967 for a thorough discussion of the inherent complexity of scheduling. Also see Hu 1982 for a computer view of the same topic.

(2) Hu 1982 offers excellent examples of the limits of computability. The renowned Dijkstra in page 3 in Dahl 1972 gives a simple but illuminating observation. See Gleick 1987 for an enthralling discussion on the modern trend to express complexity with tools of apparent chaos rather than with tools of arbitrary order.

Much heat is generated from disagreements between the two types of cost engineers: those who are intimidated by computers and rely on methods that served them for years, and those who are wedded to computers and see the entire profession as software to run, or to be written. The literature mirrors this division.1 On one hand are the good old-fashioned cost engineering books, which make cursory mention of the computer, and on the other hand, a new wave of computer books is flooding the market, with little mention of the virtues of classic cost engineering.

The prospects of the profession and its good fortune lie in a balanced approach.2

Cost Estimation

Cost estimation is the centerpiece of cost engineering. There are so many reasons costs will change, and prices will vary, that the life of a cost estimator is never too cozy. Unlike the design engineer, who deals with laws of nature — never finicky, constant, or reliable — the elements that the estimator manipulates are as dependable as the weather, as constant as a shoreline, and as avoidable as taxes.

Process engineers, architects, and designers can reach a point of ultimate accuracy. The cost estimator cannot. It is a frustration he or she must bear and live with. The most that a cost engineer can hope for is a past-perfect estimate. This is a cost estimate based on a perfect analysis of the past. It is 100% accurate if the future is a mere extrapolation of past events. To the extent that the future hides surprises, the estimate will bear discrepancies.

(1) Some pre computer era books survive the times, see Popper 1970. The “Lang Factors” introduced by Lang in 1947 are still cited, but modern literature like Cheadle 1987, Koenigseker 1982, Clark 1979, Jelen 1983, or Winklehaus 1982, as well as Tavakoli 1989, and Prerau 1987 reflect the strong emphasis on mathematical abstractions, and computer technology.

(2) See Samid 1984, and Samid 1982 for some ‘balance’ notes.

The estimator’s goal is to draw the full body of conclusions from the past and to be ready for anything the future might offer. Let us focus on these two techniques.

Learning From The Past

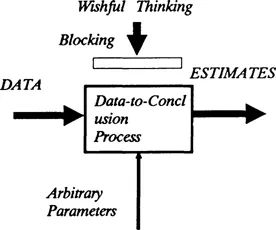

From where else? The biggest rival to the past as a teacher is “wishful thinking.” Keeping the past as the prime teacher is the duty and responsibility of the cost engineer. The dynamics are usually as follows. One track: wishful thinking expects a result, and then history is searched to support it. Track two: history is learned from, but on the way from raw data to respective conclusions, wishful thinking sneaks in and contaminates the outcome.

The mathematical techniques that lead to extracting a set of conclusions from a body of data are not well-founded. They may never be. Therefore the cost engineer has to resort to techniques which are acceptable and thereby defensible. Two dangers loom: (1) that the estimator will overlook some of the conclusion potential within the data, and (2) that he will see in the past what is not there — draw conclusions that are not warranted on the basis of what happened before. Often both discrepancies happen simultaneously during the same estimate process. See insert “producing an estimate” (fig 1.1).

fig 1.1 producing an estimate

The techniques in use are (1) sameness, (2) trending, and (3) interpolations.

Sameness

Sameness is the most common, most automatic way to learn from the past. An estimator will record a cost figure and assume that history will replay itself in the future. In noninflationary times and when technology does not shake things too much, this simple method is also the best (when it applies). It helps if the estimator has a constant supply of recent history, whether his own or from external sources. The challenge here is to keep the massive amount of cost data in an orderly fashion so that it can be found when needed and used for an estimate. The engineering challenge is to ascertain sameness validity; that is, in what case, is an historical price likely to be valid as a future cost figure?

Trending

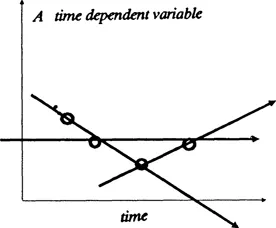

Next to sameness, trending is the most popular learning-from-the-past technique. But unlike sameness it involves a host of mathematical techniques that often sharply disagree. When a cost figure changed in a given pattern in the recent past, what does this say about its future behavior? If the estimator is lucky and the pattern is that of a straight line, then the projection seems simple. If the recent pattern is more erratic, then depending on which mathematical technique he uses, the projection will be different and in any case will be much less valid (because of diversity of opinions). See insert “forecasting uncertainty (fig 1.2).”

fig 1.2 forecasting uncertainty

The computer challenge here is to program the various forecasting algorithms, connect them to the database, and apply the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgment

- Introduction

- Table of Contents

- Part One A Computer Technology View of Cost Engineering

- Part Two A Cost Engineering View of Computer Technology

- Part Three A Utility View of Organization

- Appendices

- References

- List of Organizations

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Computer-Organized Cost Engineering by Gideon Samid,Samid in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Civil Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.