![]() PART 1

PART 1

Imagining the Far East from Europe![]()

Chapter 1

“The Indies of the West” or, the Tale of How an Imaginary Geography Circumnavigated the Globe

Ricardo Padrón

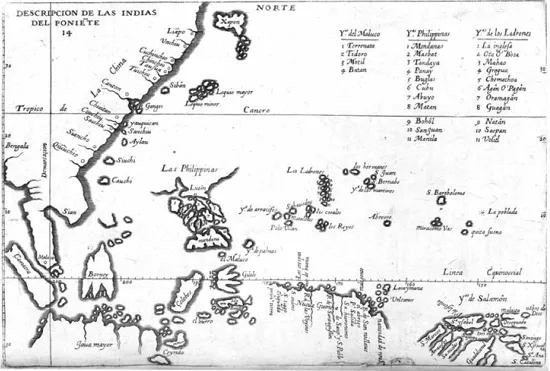

The year 1601 witnessed the publication of Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas’s Historia general de los hechos de los castellanos en las Islas y Tierra Firme del Mar Océano [General History of the Deeds of the Castilians on the Islands and Mainland of the Ocean Sea], an officially sanctioned history of Spain’s experience in the discovery and conquest of the Indies. The first volume, Descripción de las Indias Ocidentales [Description of the Occidental Indies], came accompanied by 14 maps of Spain’s possessions in the Americas and in the Far East. One of these maps, “Descripción de las Indias del Poniente” [“Description of the Indies of the West”], provides the impetus for the following pages (Figure 1.1). It depicts East and Southeast Asia, as well as the western Pacific Ocean, from Bengal in the west through 77° of longitude (by early modern Spanish calculations) toward the east, between the latitudes of 40° N and 13° S. It is not a pretty map, or a very accurate map, even by the standards of its day, but it is nonetheless an interesting one, primarily because of its inclusion in Herrera’s Historia general and because of its title.

In allowing this map and its companions to be printed, the Spanish Crown departed from its usual policy of enforced secrecy regarding the cartography of the New World. Clearly, it saw these components of the Historia general as important contributors to the larger project of Herrera’s history, that of celebrating and legitimating the overseas empire of Castile and León. In effect, these maps represent Spain’s official cartography of empire at the turn of the sixteenth into the seventeenth century. It is not a cartography of the New World or of America, but of “the Indies,” a territory that included Spain’s possessions both in the West Indies (America) and in what we usually think of as the East Indies. Moreover, it is a cartography that invites us to think about those East Indies in a puzzling way, as the “Indies of the West.” The story behind this name and its apparent attempt to remap the traditional Orient has something to tell us about the workings of the European geographical imagination at the dawn of globalization, about the role of movement and expectations in the invention of territory, and about the ways that Europeans could hold onto the fantastical geographic fictions of the past, even as their travels served to disenchant the world through which they sailed.

One might think that no genealogy is necessary. Herrera himself seems to have expected that the term would strike his readers as unusual, and offers a brief explanation for it. Early in his Descripción, he illustrates how the world is divided into four parts: Europe, Africa, Asia, and America, and boasts that his book will describe the extraordinary fourth part that has only recently been discovered, thanks to the heroic efforts of Spain. But he then qualifies this assertion by pointing out that America is only one of the territories that fall within the part of the world over which the King of Castile and León has jurisdiction. That jurisdiction extends to the entire hemisphere donated to the King by papal authority, and whose boundaries have been established through negotiation with neighboring Portugal. This entire hemisphere—the Indies, and not just America—is the subject of his book, Herrera explains. Echoing the work of earlier mapmakers in Spanish employ, the historian writes that this hemisphere embraces everything between the original line of demarcation cutting through South America at the mouth of the Amazon River, and an antimeridian drawn on the opposite side of the globe, cutting just east of the Portuguese trading center of Malacca, near modern-day Singapore. Not only the bulk of the New World, but all of the Pacific, New Guinea, insular and continental Southeast Asia, and much of East Asia fall within the boundaries of the Castilian demarcation, among the “Islands and Mainlands of the Ocean Sea” that constitute the geography of Herrera’s history. Herrera divides this expanse into three sections that correspond to three regional maps: the “Indies of the North” (North America), the “Indies of the South” (South America), and the “Indies of the West.” He explains that this third part includes the territories just east of Malacca, on the Castilian side of the antimeridian, and adds: “although they are part of Oriental India, they are called of the West, relative to Castile.”1 This simple explanation for a toponym wrought out of a complex history of greed, ambition, violence, rivalry, and daring has much common-sense appeal, the sort of appeal that often comes from the operation of a powerful yet unacknowledged ideology. I am not referring to the ideology so manifestly at issue, that is, the Castilian patriotism so in evidence in the placement of the line of demarcation and the antimeridian.

Fig. 1.1 “Descripción de las Indias del Poniente” from Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas, Historia general de los hechos de los castellanos en las Islas de tierra firme del mar oceano (1601).

In an age that could not determine longitude with any precision, and in which a number of crucial geographical variables were open to contestation, it was possible for mapmakers to slice up the world differently, according to the interests of the kings they served, and still claim that their maps demonstrated methodological rigor and responded to empirical evidence. Herrera’s text pays some lip service to the difficulties involved and to the controversy over the placement of the lines, but never entertains the full extent of Portugal’s counter-claims, and presents the position of the lines favored by Castile as a matter of fact. Yet, there is another ideology that runs even deeper than this obvious cartographic jingoism, which is rooted in the very nature of maps and mapping itself. Maps have become famous during recent years for the clever ways in which they serve particular interests while ostensibly representing objective realities.2 Like other discourses of power, they often naturalize what is contingent.

In Herrera’s Descripción, ironically, the power of the maps derives from an admission that one of its conventions is precisely that. He explains to the reader that the “Indies of the West” are really part of the East Indies (Oriental India), but are called western because they lie “west of Castile.” In other words, he acknowledges that their identification as “eastern” is natural, while their identification as “western” is conventional. Upon reflection, we see that the frankness of this apparently self-sabotaging concession actually serves to forestall scrutiny of what is being admitted. We forget for a moment that the Earth is round, and that the territory in question lies just as much to the east as to the west of Castile, particularly when we think in terms of the abstractions of longitude rather than the physical geography of continents. We forget also that the adoption of either (the) term “eastern” or “western” is predicated on privileging Europe as the center from which other locations are designated. The choice between the two is really the choice between a long-standing convention that happened to serve Portuguese interests, and a novel convention that arose out of Castile’s long-standing rivalry with its neighbor. Herrera deals only in putative realities (these lands form part of “Oriental India”) and the reorganization of reality through the work of an objective cartography (the line of demarcation really lies where he says it does). The line of demarcation thereby obscures the history of rivalry and struggle that has reinvented “the Indies” as precisely “the Indies of the West.”

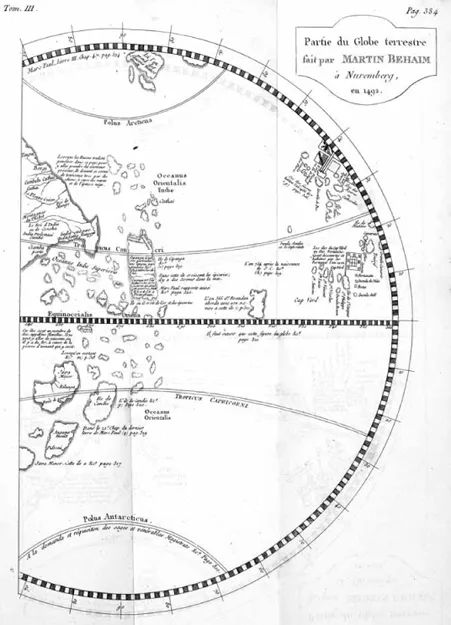

Here I propose to recover this history, or at least its general outline. I begin by going back a little over a century before the publication of Historia general, to a time when it was possible to speak of “the Indies” free from the confusion about its location wrought by the relativity inherent in globalism. Nicolás Wey-Gómez describes “the Indies” of the late medieval geographical tradition as a “maritime system” made up of islands and continental coastlines extending “all the way from an oceanic archipelago that included the island of Cipangu to the coast of Mangi, to the coast of Ciamba, to Indonesian islands like Java Maior and Java Minor, to the inner shores and islands of the Indian Ocean itself, and to the African islands of Madagascar and Zanzibar.”3 They appear as such on many maps and globes from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, but I will follow Wey-Gómez’s lead in using as my example the globe produced in 1492 by Martin Behaim, a Bohemian explorer and geographer who resided in Lisbon and the Azores during the 1480s (Figure 1.2). On the globe we see a large island out in the ocean east of the Asian mainland, pierced through by the Tropic of Cancer. This is Cipangu, where Marco Polo reports there was gold “abundant beyond all measure,” and to the southwest of it are some of the other islands Wey-Gómez mentions, including Java Maior and Java Minor, as well as Ceilan.4 An abundant archipelago thought to be rich with gold, spices, pearls, and precious stones, as well as monsters, surrounds Cipangu and stretches southwestward to these other major islands. Their appearance on the map echoes the reports of medieval travelers. Marco Polo, for example, reported that the “Sea of India” contained 12,700 islands, inhabited and uninhabited, and claimed that “no man on earth could give you a true account of the whole of the Islands of India,” so great was their number.5

This plethora of unnamed islands appears on other late medieval maps, like the “Catalan Atlas” (1375) and “Fra Mauro’s World Map” (1459), as well as on sixteenth-century maps, such as on a Portuguese chart from the so-called “Miller Atlas” (1519) in the collection of France’s Bibliothéque Nationale (Figure 1.3). We might be tempted to think about these islands as a very imprecise representation of the area we know as insular Southeast Asia—modern day Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and even Papua New Guinea—but this is a temptation that we must resist. This multitude of islands, referred to on the “Miller Atlas” chart as a multitudo insularum, is no more a representation of insular Southeast Asia than the figure of the Terra Australis Incognita on other Renaissance maps is a representation of the continents of Antarctica or Australia. Like the Terra Australis, the multitudo insularum sprang from the realities of experience—the travels of medieval Europeans to Asia—but was transformed by the European imagination into something more fantastical than real. Indeed, it is even possible to question the basic mimetic function of their cartographic representation. Referring to their appearance on the “Miller Atlas” chart, Christian Jacob captures their uniform hue and capricious coloration as signs of their non-mimetic quality:

The oceans are filled with luxurious archipelagoes, with lively colors and aleatory forms, as if these islands were being represented metaphorically as precious stones, the dream of which continued to haunt both travelers and sailors […] Colors and forms do not have extrinsic meanings. They are identified with an aesthetic effect.6

Fig. 1.2 Detail of Martin Behaim’s 1492 globe, reproduced in Antonio de Pigafetta, Premier voyage autour du monde (1801).

This figure has intentionally been removed for copyright reasons. To view this image, please refer to the printed version of this book

Fig. 1.3 Detail from chart of the East Indies, Miller Atlas (1519).

For Jacob, the islands serve to both tantalize and frustrate. Inaccessible to knowledge and navigation, they appear as objects of desire that will remain forever out of reac...